Month: May 2014

The fantastic insults of Robert Burns!

And the winner is… Thou pickle-herring in the puppet-show of nonsense!

For the full letter from which these spectacular insults came, see Letters of Note

Glorious Gardens…

It’s no secret that Robert Burns loved nature, and we at RBBM are very proud of the wonderful gardens that are part of our site. Last weekend’s ‘Glorious Gardens’ event showcased the fantastic work of our gardeners, as well as providing many other exciting activities for all the family.

The museum foyer played host to a variety of craft stalls, and we were even visited by some bees… every garden’s best friend!

Meanwhile, our regular Farmer’s Market was in full swing in the Robertson Room…

…and our learning team were running a stone painting stall for the bairns, although in house rivalries were quickly becoming apparent. The debate over who can paint the best ladybird still rages!

Add this to the garden tours, led by our head gardener David, and our regular weekend Highlight Tours of the museum and cottage, and it’s safe to say that there was plenty to keep people occupied.

We hope all our visitors enjoyed the day, and would like to thank everybody who was involved in making the event such a success.

Robert Burns and the Slave Trade: Part 3, Boswell’s case for the defence

James Boswell is best known as the companion and biographer of Dr. Johnson, the author of ‘Johnson’s Dictionary’, but he was also an Ayrshire compatriot of Robert Burns. Despite their shared home and friends in common, Robert Burns and James Boswell never actually met. One reason for this may be that the conservative, Tory, wannabe-MP Boswell may have been worried about the negative impact that meeting Robert Burns, supporter of the French and American Revolutions, may have had to his career. It is therefore interesting to see Boswell as an upper-class parallel to Burns, and his views on slavery and the slave trade are worth exploring.

We know that Boswell started out opposed to the slave trade. As a young lawyer he was part of the defence team for Joseph Knight. This famous case involved a young man, Joseph Knight, who had run away from his master, John Wedderburn, while they were in Scotland. Knight then took Wedderburn to court, and won. The case established a precedent that slavery is illegal in Scotland … although it did not suggest that slavery in British Colonies was illegal. This would seem to put Boswell in the anti-slavery camp, and indeed, in 1787 he attended a meeting of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

However, it was not long before Boswell appeared to have changed his mind, and became a supporter of the slave trade. Boswell always fancied himself as a gentleman rhymer, so it was natural for him to put his arguments forward in his pro-slavery poem of 1791, ‘No Abolition of Slavery; or the Universal Empire of Love’.

Boswell began his poem by addressing the abolitionists:

Noodles, who rave for abolition

Of th’ African’s improv’d condition,

At your own cost fine projects try;

Dont rob—from pure humanity.

Basically, instead of picking on plantation-owners, why don’t you make the world better in a way that eats into your own purse? Worse than this, the common people are getting involved in the debate, rather than leaving the issue of the slave trade to parliament, who always know best:

What frenzies will a rabble seize

In lax luxurious days, like these;

The People’s Majesty, forsooth,

Must fix our rights, define our truth

And worse than the people getting involved, SCOTLAND wants to have a say as well! Like many other of his countrymen departed to make their fortune in London, Boswell here turns on his birth-country:

Ev’n bony Scotland with her dirk,

Nay, her starv’d presbyterian kirk,

With ignorant effrontery prays

Britain to dim the western rays,

Which while they on our island fall

Give warmth and splendour to us all.

So far, Boswell has denigrated the people who are making the anti-slave trade argument, and saying that they do not know what they are talking about. Next he makes the argument, also made by Dr. James Makittrick Adair, that the slaves are better off than certain members of society and that they actually enjoy being slaves:

The cheerful gang!—the negroes see

Perform the task of industry:

Of food, clothes, cleanly lodging sure,

Each has his property secure;

Their wives and children are protected,

In sickness they are not neglected;

While Burns appears to have begun life – perhaps – uninformed about the slave trade and then became more radical and opposed to slavery, Boswell seems to have taken the opposite route, and while he started as a defender of slaves, ended up as a defender of slavery.

Burns in Irvine

We always tend to associate Robert Burns with farming. Indeed he spent many years of his life at Mount Oliphant and Lochlie, in Tarbolton, also Mossgeil in Mauchline, and latterly Ellisland Farm in Dumfries. When he was Edinburgh, with a view to having his poems published, he was hailed as the Heaven Taught Ploughman by Henry McKenzie… the man who wrote one of Burns’s favourite books, The Man of Feeling.

When Burns was 23, he saw the lack of aim and purpose in his life and resolved to do something about it. He wrote: ‘My twenty third year was to me an important era. Partly through whim and partly that I wished to do something in life, I joined with a flax dresser in a neighbouring town, to learn his trade and carry on the business of manufacturing and retailing flax.’

Robert and his brother Gilbert had for a few years grown flax at Lochlie farm. They had rented three acres of their father’s land in which to grow this crop, which grew very successfully due to the clay soil and damp conditions. One year, Burns was awarded a government grant of three pounds and ten shillings for the production of flax seed for growing.

The neighbouring town of Irvine was about ten miles from Tarbolton, and was then the largest town in Ayrshire. It would seem that Robert invested a sum of money in this venture. His partner was a Mr Peacock, thought to be half-brother to his mother Agnes. Burns described him as a scoundrel, who also made money by the mystery of thieving.

The work of dressing flax was carried out in heckling sheds at No. 10 Glasgow Vennel. There were two sheds, one used for heckling and the other as a store room and stable. Robert slept in the loft of the store room. The work of heckling was long and arduous, and Robert spent about ten hours a day combing the flax, which produced clouds of choking flint and dust. After a few months of working in these conditions, Robert began to feel very unwell. A doctor was sent for, and Dr Fleeming came to visit him five times in eight days. It was not known what his illness was, but he was suffering from a very black bout of depression, as well as being in a lot of pain and seemingly having a fever. His doctor prescribed various things for him.

Many years later, in 1950, Dr Fleeming’s record book was found an attic by a pharmacist who bought his house. As he flicked through the pages, he saw the name: Robert Burns, flax dresser. The doctor had recorded the dates of his visits to Burns and also what he had prescribed, but had not recorded a diagnosis or prognosis.

Burns became so ill that his father came to visit him from Tarbolton. When he saw the dreadful and insanitary conditions his son was living in, he arranged for him to be moved out of the store room where he slept and into a room at No. 4 Glasgow Vennel. Burns wrote a letter to his father on the 27th December, 1781 telling him he was: ‘quite transported at the thought that ere long, perhaps soon, I shall bid an eternal adieu to the pain and weariness of life, for I am heartily sick of it’.

He was deeply depressed, and all he could see ahead of him was poverty and obscurity. He also wrote that he had been reading the Revelation verses 15, 16 and 17: ‘It speaks of no more suffering, no more sorrow, no more pain, and that God will wipe away all tears from all eyes.’ He seems to have been particularly fond of those verses and has quoted them in other letters.

Four days after he wrote that letter, worse was to come… the heckling shed was burned down by the carelessness of his drunken partner’s wife, Mrs Peacock. It was burnt to ashes and Robert lamented: ‘It left me like a true poet, not worth a sixpence’.

He stayed on in Irvine for a number of weeks after the fire, having formed a close relationship with a seafarer by the name of Richard Brown. It is not known where they met, but Brown was six years older than Burns, had had mixed fortunes, and had some education. They spent a lot of time together, talking and walking in Eglinton woods. Robert loved him and admired him and to a degree he strove to imitate him: Brown had a knowledge of the world and Robert was all attention to learn. Robert used to recite his poems to Brown was they walked, and one day Brown encouraged him to consider having his poems printed. The seed was planted in Burns that day.

I think that the most significant thing to have come out of Robert’s time in Irvine was his discovery of Robert Fergusson, the young Edinburgh poet. Born in 1750, his collected works were published in 1773 and he sold 500 copies. It is not known where Robert came across Fergusson’s works. It was perhaps in Willie Templeton’s bookshop at Irvine cross, at which Burns was a regular visitor. Burns felt an emotional kinship with Fergusson and later wrote:

‘Oh thou my elder brother in misfortune

By far my elder brother in the muse

With tears I pity thy unhappy fate’

A few years later, Burns commissioned a memorial stone for Fergusson’s unmarked grave in Cannongate, and in the preface to his Kilmarnock edition in 1786, he referred to him as ‘the poor unfortunate Fergusson’. He wrote in an autobiographical letter: ‘meeting with Fergusson’s Scotch poems, I strung anew my wildly sounding rustic lyre with emulating vigour’. He also said that Fergusson had made him come alive as a poet. He was greatly influenced by Fergusson, as we can see in the Mauchline Holy Fair, inspired by Leith Races.

Burns left Irvine in March 1782 and returned to Lochlie farm in Tarbolton. He had returned for the ploughing and planting season.

And so it was that he was back where he started, but as a very much wiser man. He also had a new aim in life: to become a poet and have his work printed some day.

This blog was written by one of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum’s dedicated volunteers, Ann Hamilton, who delivered a Highlight Talk on the subject last month. Many thanks to her for all her hard work and research.

Address to a Rubik’s Cube, upon the celebration of its 40th birthday

Wee awefu’ devilish Rubik’s Cube,

You mak me feel like sic a newb,

I’d rather sit an watch the tube,

Than try an fix thee.

My heid is gangin loop the loop,

An A’m feelin dizzy.

Robert Burns and the slave trade – Part 2: Makittrick and Son

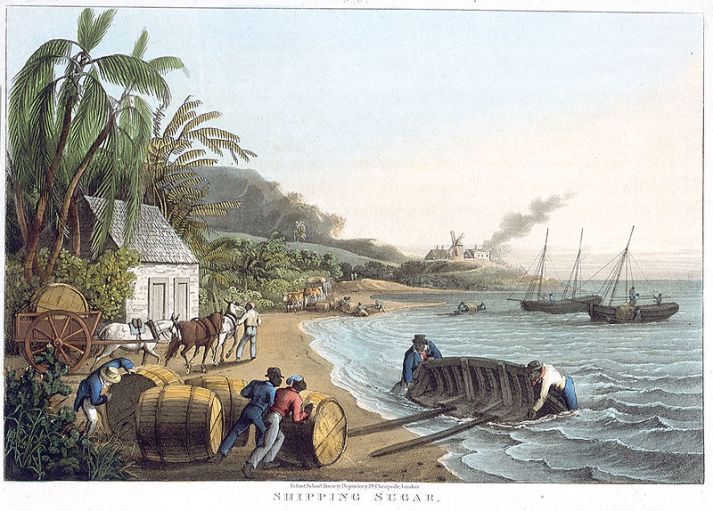

James Makittrick Adair was born in 1728 to the Ayr doctor, James Makittrick. James Makittrick Adair decided to practise medicine as well. James Makittrick Adair’s son – also named James Makittrick Adair – also became a doctor. James Makittrick Adair (junior) would go on to travel with Robert Burns to Harvieston in 1787. Makittrick Adair junior married Charlotte Hamilton, a woman who Burns himself may have had his eye on, as she was the inspiration for the love song ‘the Banks of Devon’. However, it is Dr. James Makittrick Adair senior (son of Dr. James Makittrick, father of Dr. James Makittrick Adair) that this article is interested in. Rather than practising in Ayr like his father, Adair took the route followed by many other Scots during the boom time of the West Indian sugar trade, and went to Antigua. On Antigua, Adair was appointed physician to the troops stationed at Fort Great George, and also became a slave-owner. Having made money and connexions, Adair returned to Britain in 1787 (the same year that his son was travelling with Burns) and set up as a doctor in uber-fashionable Bath.

James Makittrick Adair senior seems to have been a likeable man, he wrote essays poking fun at high society hypochondriacs who were convinced they had ‘fashionable diseases’ and he denounced quack doctors, this tendency to be opinionated also got him in trouble, he was jailed for duelling, and got caught up in the sort of violently libellous pamphlet wars that epitomised the literary eighteenth century. Adair died in 1801, and you can see his gravestone just round the back of Alloway Auld Kirk, propped up against the wall.

As well as epitomising the many Scots who practised medicine in the British colonies, James Makittrick Adair also represents the Scots who profited from and defended the slave trade. Adair made his views on the slave trade clear in 1790, when he wrote the unambiguously titled ‘Unanswerable Arguments Against the Abolition of the Slave Trade’.

The way that European slave traders received their slaves in Africa was that Africans would sell Africans of another tribe or nation into slavery, often these people had been captured during inter-tribal warfare. Some abolitionists had pointed out that not only were the Europeans taking advantage of these inter-tribal conflicts, but that these conflicts were sometimes caused by one tribe attacking another tribe so that they could capture slaves.

Adair believed the opposite, in fact he went so far as to say that the slave trade:

‘…is probably permitted by Providence, as the means of preserving the lives of many thousands who would otherwise be put to death…’

One of Adair’s early points is that we in Europe will always want and need sugar, so sugar will need to be produced by someone. If we decide to abolish the slave trade, it would be impossible for British planters to run sugar plantations and sell sugar, so not only would Britain lose money from trade, but we in Britain would still need to buy sugar from someone, perhaps even from our enemies the Dutch or the French, and they would still use slaves. Adair muses ‘whether we shall be in a degree less culpable in abetting slavery indirectly by purchasing the fruits of it from foreigners, rather than from our own subjects.’

Instead of moaning about the plight of the slaves, Adair asks that we consider the West Indian planters for once. Adair points out that the planters wouldn’t import slaves if they didn’t have to. ‘would the planters oppose the abolition, were they convinced that they could conduct these plantations without annual recruits?’

Of course not! Buying slaves is a massive expense, and means that the planters’ ‘disposition to live in an expensive stile [is] much restrained’

Far from living in luxury, Adair claims that the planters are in massive debt as it is

‘and struggling, like a drowning man, to keep his head above water, the abolition of the slave trade must, inevitably, sink him into the abyss of ruin, and he will drag the British Empire along with him’

While talking about the cruel punishment of slaves, Adair said that the larger number of African slaves when compared to white planters, meant that the planters needed to use harsh discipline as a way of keeping their slaves in line, ‘rigid discipline [was] their only security against insurrection’. Elsewhere, Adair warned his British readers not to put abolitionist ideas into the slaves heads, as the idea that they could achieve freedom‘may produce a general revolt’, which would be ruinous for the colonies and for the mother country.

The fear of slave uprisings is one shared by the defenders of slavery, and was a common reason given as to why slaves should not be freed. In the case of eighteenth century slave-owners, these fears of uprisings were well-founded. The massively profitable French sugar colony of Saint Domingue had a population that contained ten times as many African slaves as it did black or white free citizen. In 1791, news of the French Revolution and the supposed equality of all men, led the slaves on Saint Domingue to revolt, this conflict lasted from 1791 to 1804, and led to the foundation of the Republic of Haiti. It was the only slave revolt ever to achieve full success. An ugly culmination – though one that mirrored the French Terror – to the Haitian Revolution came in 1804, when Jean Jacques Dessalines, the first emperor of the new republic, ordered the massacre of the remaining white population of Haiti. 3-5000 men, women and children were allegedly slaughtered in this act of revenge and consolidation.

Dr. James Makittrick Adair wrote his defence of the slave trade in 1790, during the opening stages of the abolitionist movement in Britain. In the next article in this series I will explore the work of another contemporary of Robert Burns who defended the slave trade, a man whose name is better known to us than all three of the Doctors Makittrick, his name was James Boswell.

Robert Burns and the Slave Trade: Part 1, The Slave’s spicy forests

The Slave’s spicy forests, and gold-bubbling fountains,

The brave Caledonian views wi’ disdain;

He wanders as free as the winds of his mountains,

Save Love’s willing fetters, the chains o’ his Jean.

In this song of 1795 Robert Burns rejected the slave plantations of the Americas in favour of ‘Cauld Caledonia’, yet less than 10 years earlier his situation was quite different.

In 1786 Robert Burns was in dire financial straits, and seriously considered emigrating to Jamaica to working as a book-keeper on a sugar plantation that used slave labour, a position that had been offered to him by the plantation owner, the Ayr-based Dr. Patrick Douglas. It may even be that Burns published the first edition of his poems – the Kilmarnock edition – as a way of raising funds for his passage to Jamaica. As it happened, the reception to the poems was so positive that Burns delayed his planned emigration. Burns later recalled that ‘I had taken the last farewell of my few friends, my chest was on the road to Greenock; I had composed the last song I should ever measure in Scotland – ‘The Gloomy night is gathering fast’ – when a letter from Dr Blacklock to a friend of mine overthrew all my schemes, by opening new prospects to my poetic ambition.’

This is all part of the legend of Burns. Here was the heaven-taught ploughman who – at the moment of desperation – won the hearts of the Scottish literati, and is still remembered today.

That Burns never went to work on a slave plantation is obvious to us now, but it was a very common and attractive career-choice for many other Scots around this time. It was through luck, not conviction, that Scotland’s bard avoided working on a slave plantation. We are also lucky that Burns never emigrated, this is partly because he would very probably have died even younger than he did. The standard career trajectory of Scots and other Europeans working in the West Indies was to make as much money as fast as possible, and then return home to build their estate and escape tropical disease. If Burns had died in his twenties in Jamaica, we may not have gained canon of songs of poems written and collected by Burns, and if we had, his work would be tainted by its association with the slave trade.

Robert Burns was never massively outspoken against the slave trade, although works such as ‘the Slaves Lament’ mean that he could not be described as pro-slavery. While Robert Burns never defended the slave trade, he profited from it indirectly, as we all have in modern Scotland.

In the next blog entry in this series I will explore the career of Dr. James Makittrick Adair, the defender of the slave trade who is buried in Robert Burns’ backyard.

Early gems adorning

The Scottish spring is in full swing around the museum gardens and there are ‘early gems’ popping up everywhere you look. Some of Burns most famous and well kent works are his vivid nature poems and below are some of the flowers he would have known and as such, immortalised in verse. Admittedly, some of these are different varieties than he might have been familiar with (I’m looking at you Californian poppy), but beautiful nonetheless.

For more pictures of the Monument Gardens, look us up on Pinterest!