Art

Goudie’s Dazzling Tam o’ Shanter Paintings

Tam o’ Shanter is Robert Burns’s masterpiece. A long, narrative, epic poem written in 1790 by Burns whilst living at Ellisland Farm, Dumfriesshire and published in Captain Francis Grose’s Antiquities of Scotland in 1791. Burns apparently wrote this in only one night and it appeared in the book just as a footnote! Now Burns was known to have enjoyed superstitious, supernatural stories as a child. His Aunty- a Betty Davison – told him many and Burns said that“[she] had, I suppose, the largest collection in the country of tales and songs, concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, inchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery.”[1] The poem is full of wild scenes, dramatic and exciting twists and turns, bloody and gothic content as well as witty machoism through the characters and their antics.

Many artists have been inspired by the poem and some of the artwork produced really brings the poem to life. Some of the most expansive and impressive works are that of Alexander Goudie. He was apparently totally obsessed by Tam o’ Shanter and his lifelong aim was to create 54 complete cycles of images inspired by the epic tale. He accomplished this and the results are spectacular. A select few will be shown and analysed below.

This painting refers to the first two lines of the poem:

When chapman billies leave the street,

And drouthy neibors, neibors meet;

This scene is full of vibrant colours, objects and action: Tam looks well, as does Meg, and they are surrounded by other animals and people greeting them warmly. It is arguably one of the best paintings in the cycle as it has been painted with such attention to detail. This could reflect that this is the part of the poem before Tam boozes at the nappy, thus, he is not intoxicated and he will have a clearer vision now compared to the rest of the poem. The reflection in the window is very life-like as is the woman pulling the curtain aside to have a good nosey at what is happening on the street. It is worth noting that this painting is number twelve – even though it refers to the first two lines of the poem – so Goudie has used his artistic licence and imagination to fill in the gaps of what happened before this point as well as not putting the images in order according to the lines of the poem i.e. No. 11 “As market days are wearing late” is the line after No. 12 “And drouthy neibors, neibors meet” but it comes before it in the cycle.

This of course refers to the beautiful and philosophical extract:

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed;

Or like the Borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the Rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.

This is typical Burns: returning to nature which is his greatest source of inspiration. In the painting Goudie has shown a scene that is a delicate paradise. A moment captured in time with two lovers lying in a field, with the man picking a poppy, and the rainbow overhead. This is very contradictory to the shock and horror that is to follow…

This is one of three images that are in black and white; although this one here has Tam’s clothes clearly visible, with the famous blue tam hat and yellow waistcoat drawing the eye, which isolates him even more so. The crack of lightning has inspired the use of black and white and Goudie has depicted a truly spooky scene with the trees looking ghostly bare and the town and bridge totally empty. It is preparing the viewer for what is about to come next…

This is one of the treasures of the collection. It depicts the chaotic and shocking scene Tam beholds once he has approached the kirk: as a viewer you do not know where to look as it is so full of action and faces. This refers to the below section of the poem which is full of vivid imagery:

Warlocks and witches in a dance:

Nae cotillion, brent new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

A winnock-bunker in the east,

There sat auld Nick in shape o’ beast;

A towzie tyke, black, grim, and large,

To gie them music was his charge:

He screw’d the pipes and gart them skirl,

Till roof and rafters a’ did dirl.

Coffins stood round, like open presses,

That shaw’d the Dead in their last dresses;

And ( by some devilish cantraip sleight)

Each in its cauld hand held a light.

You can clearly see the devil glowering in the back corner, with his bagpipes in hand and mouth, casting a huge shadow on the back wall; the witches and warlocks are in a dance spinning each other around; the numerous coffins encircling the dancers with their skeletons holding candles as light. There is nakedness; there is sorcery going on at the table; the full moon can be seen through the window and the party-goers are oblivious to Tam’s presence.

This is another gem of the collection which is similar in the colour and the grotesque but exciting scene depicted as No.31. Tam and Meg are at the mouth of hell itself about to be devoured by the bright flames and are surrounded by all sorts of characters and mythical creatures who are all armed with weapons. Interestingly, the priest and lawyer are present, this inclusion of was famously shocking of Burns back in the eighteenth century. This is a scene which Tam and Meg did not actually suffer but it is a prediction – an insight into the future – of what will happen if they do not escape the ghoulish mob.

This is the moment which Nannie latches onto Meg’s tail just before they get to the key-stone. It refers to this section of the poem:

Now do thy speedy utmost, Meg,

And win the key-stane o’ the brig:

There, at them thou thy tail may toss,

A running stream they dare na cross.

But ere the keystane she could make,

The feint a tale she had to shake!

For Nannie, far before the rest,

Hard upon noble Maggie prest.

And flew at Tam wi’ furious ettle;

But little wist she Maggie’s mettle!

Ae spring brought off her master hale,

But left behind her ain grey tail:

The carlin claught her by the rump,

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

What I like about this interpretation most is that Tam is positively terrified, not composed at all, and has come off his saddle and is hanging around poor Meg’s neck. Tam o’ Shanter has a bit of sexism in it with all the drinking, men will be men, flirting with the barmaid whilst the wife is at home worrying drama in it but here Goudie has depicted Tam as being utterly at the mercy of a powerful female character: more so than as how Burns depicted him as Goudie has him literally hanging on for dear life.

This final image is in reference to the conclusion of the poem:

Now, wha this tale o’ truth shall read,

Ilk man and mother’s son, take heed:

Whene’er to Drink you are inclin’d,

Or Cutty-sarks rin in your mind,

Think! ye may buy the joys o’er dear;

Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mare.

Here Goudie has used his artistic licence again to create the scene he must have imagined when reading this ending. With only Tam and Meg in the painting: your sole focus is on them. Tam looks haggard, totally drained and panting heavily with his tongue sticking out. He looks like he has aged ten years form his traumatic experience. Meg – the hero of the poem – has also suffered this dramatic change same as Tam. Yes, her tail is gone with only the bloody stump left but she looks aged, thin – bony even – and is cowering by Tam with her head down in fear and she has soiled herself. Altogether, it is not a pretty sight, but a great visualisation of the moral warning in which the poem ends.

All of these paintings are now in the collection of Rozelle House Galleries (and some are on permanent display). This is situated in a historic mansion, surrounded by beautiful grounds and also boasts a tea room too. It is just a two minute drive away from the Burns Cottage and only six minutes from Ayr town centre. I would thoroughly recommend any art or Tam o’ Shanter lover to visit.

By Parris Joyce, Learning Trainee

[1] The Bard by Robert Crawford, p20

Useful link:

Was Robbie Radical?

This iconic and vivid red poster definitely catches the een, however, at first glance you think you see the famous revolutionary Che Guevara in the Andy Warhol like pop art print – but, naw readers you’d be mistaken – its Robbie! Cleverly the University of West of Scotland have mischievously replaced Guevara’s face with Burns’s to stand as Scotland’s most well-known and well-loved revolutionary.

The posters purpose is to recruit students to study Scottish culture, and who best to represent that, than the greatest Scottish bard of all time. Popular culture ideas and images of Burns in the twenty-first century have made him a national favourite and his mug is surely recognizable by any true Scot. I mean he’s even got a national day after him (which outshines St Andrew’s day in Scotland!) An example of just how famous Burns is thought to be is conveyed in the pop art featured in the exhibition space of the RBBM.

Burns is seated at a dinner table next to the likes of Nelson Mandela, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Munroe and Mohammed Ali like a modern-day Jesus Christ hosting a Last Supper… all these celebrities are renowned for being extraordinary individuals and for revolutionizing their individual fields. But was Robert Burns revolutionary?

I wid argue, that through his works, he wis aye. The poems Scots Wha Hae, A Man’s a Man for a’ That and The Rights of Woman all are inherently radical based on their political subjects and they are full of powerful, and sometimes emotive, language.

Tyrants fall in every foe!

Liberty’s in every blow!

Let us do – or die!!

Tyrannical government was the object of American and European reformers and “liberty” was a 17th and 18th-century watchword.

Burns may not have been bodily present or involved in revolutionary activities but he was there in spirit and mind. His works are deeply imbedded with hope for change.

All in all, Burns has become the personification of Scottish identity and is a legend as his works and life are continued to be studied, celebrated and preserved the world over, hundreds of years after his death… If that doesnae make ye radical, then a dinny ken wit does.

By Parris Joyce

Burns’s relationship with the Kirk

Earlier this year, two students from the Scottish literature department at Glasgow Uni joined us on a month long placement as part of their degree. This is the first in a series of four blog posts they wrote between them on elements of the exhibition they found significant.

During his lifetime, Burns was inspired by many different things, but one of the most significant aspects – which gave him plenty of creative fodder to chew on – was the oppressive control the Scottish Presbyterian Church held over not only the people within his own locality, who provided his primary concern, but the entire nation. In its ‘A Cauld Kirk’ section, the museum chooses poems which reflect this: ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’, ‘The Holy Fair’, and ‘The Holy Tulzie’. Burns’s religious satire is a rich source for one who wishes to observe the religious climate of the late eighteenth century, and so we must recognise that our present-day attitudes towards Burns’s contemporary Kirk have probably been largely shaped by his poetry. However, Burns’s religion has often been misunderstood by readers and critics alike – Burns was not an enemy of religion, nor a pious Presbyterian, but we can be sure from his satire that he hated religious hypocrisy. Around the time Burns was writing, a rift was beginning to appear within the Church of Scotland. There appeared two branches of Presbyterianism – the ‘Auld Lichts’ who represented a more severe and unforgiving form of Presbyterianism, Calvinism, which involved fire and brimstone sermons and the idea of predestination which Burns so despised. The ‘New Lichts’, with whom Burns shared sentiments and could really get behind, represented a more moderate form of Presbyterianism which sought to put more emphasis on morality and the human aspects of religion, rather than just being blindly faithful.

It cannot be denied that Burns’s religious satire is an attack on the ‘Auld Lichts’. Ever since the Reformation, individual Kirks within small communities held supposedly God-given authority over their people – and they ruled by fear. To illustrate this, the museum allows you to put yourself in Burns’s riding boots by taking a seat on the ‘cutty-stool’ or ‘creepie-chair’, situated in front of the pulpit and therefore the entire congregation. This chair is not dissimilar to the naughty-step your parents might have chastised you on, and in it Burns would have sat and been told off in front of his family and good friends, as well as he entire village of Mauchline, and this did not sit well with him at all. Burns willingly sat in similar sermons all over the country – he was a ‘sermon-taster’ – but it was his experiences within the Mauchline Kirk which inspired poems such as ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ and ‘The Holy Fair’. However, the museum does acknowledge the fact that Burns’s religious allegiances were not as clear cut as they may appear in his satirical poetry by recognising his relationship with ‘Auld Licht’ minister William Dalrymple, whom Burns admired and respected for his liberal views – it is well known that Burns was a man of many contradictions.

Hanging in the ‘A Cauld Kirk’ section is Alexander Carse’s painting ‘The Mauchline Holy Fair’, a depiction of the twice-yearly gathering described in ‘The Holy Fair’. If you look carefully at it you might notice a character resembling Burns, sporting a rather mischievous smile, walking alongside the bright and beautiful personification of Fun, closely followed by the dark, grim, Calvinist-type women representing Superstition and Hypocrisy. Mauchline Kirk is painted at the left, the pub on the right, and between them the village community, caught up in a kind of moral tug-of-war. Carse depicts the villagers as Burns would have recognised them, as individuals caught up on the tension between religion and traditional culture. This moral tug-of-war was about deciding whether to embrace their freedom – drink, chat, eat, and flirt until there heart was content – or to behave themselves and not risk public condemnation in the sermon. We see now that these people lived in constant fear of the Kirk and its authority – one foot out of place was all it took. Burns was a fond observer of human nature and he recognised that in order to be reformed, the Kirk must take moral weakness and human frailty into account.

This exhibit is only a small sample of what Burns’s moderate Presbyterianism and relationship with the Kirk has inspired, and it is important we remember the unjust Kirk practices that inspired Burns to write, so that people never have to live in fear of being ‘only human’ again.

By Kirsty MacQueen

Behind the Scenes

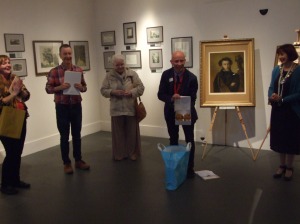

In this blogpost we go behind the scenes of our temporary exhibition, The Real Face of Burns, to speak with exhibition’s curator, Sheilagh Tennant of Artruist (www.artruist.com). For the last three years, at RBBM, Sheilagh has been managing and curating the first rolling programme of contemporary art exhibitions to be introduced at an NTS property. But what is it like to run art exhibitions? Read below and find out!

How did you come up with the concept for this exhibition?

Well I was aware that Burns’s appearance seemed to be a source of fascination for both artists and the wider public and so decided to explore this. I was amazed to discover there were so few portraits of him painted while he was still alive – only five – and thought it would be interesting to invite contemporary artists to come up with new interpretations.

How long does it take to organise an exhibition like this?

People would be surprised by how long it takes to organise exhibitions – in national galleries and museums it can take several years. However for the Real Face of Burns, while I initially came up with the idea a few years ago, if we take the initial artist approaches as a starting point, the process began just over a year before the launch date.

How do you find and select the artists for the exhibition?

By visiting as many art fairs and exhibitions, going to as many degree shows as possible, as well as reading art publications – over time it’s possible to become familiar with a lot of artists’ work and to build up a good awareness of who is out there. In this way, when a theme is selected, artists whose practice would ‘fit’ with a particular theme will come to mind. I also aim to introduce new graduates whenever possible. A selection of different work in different media , all aiming to depict an aspect of the same theme, somehow always looks good together when all the artists are clearly very gifted – regardless of the age and stage of the artists. I do find it particularly rewarding to have the opportunity to nurture new talent.

What do you need to consider when arranging the display?

Well there are, of course, the practical considerations of what is physically possible within a space, safety etc. Beyond that you have to think about works which will complement each other and, while perfect symmetry isn’t going to be a realistic aim, it’s ideal to achieve a balance within the space.

What is your favourite thing about this exhibition?

For this exhibition the answer has to be the Reid miniature, loaned by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery – to me it is so precious because Burns himself believed this work to have offered the best likeness.

What is the most difficult thing about putting on this exhibition?

To be honest there haven’t been any significant difficulties with putting on this exhibition! However I would say the most difficult aspect of all the exhibitions I have curated in this programme, which has been running for three years now, has been getting the message out to people that these shows are on and worth a visit – especially when the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum has so much else to offer too!

Come and see the Real Face of Burns before it ends on June 14th!

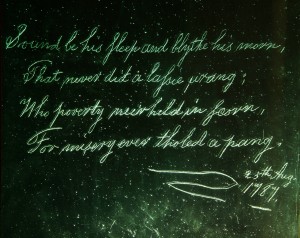

Will the Real Robert Burns Please Stand Up?

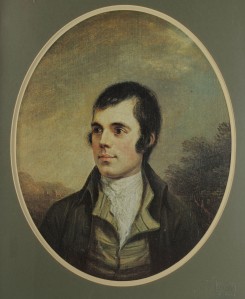

Our forthcoming exhibition, The Real Face of Burns, explores the legend of imagery that has grown up around our bard. While we think we know what Burns looked like, the majority of Burns imagery is based on a portrait done by the artist, Alexander Naysmith. Yet, while Naysmith knew Burns, the other images done during the life of Burns seem to conflict. Who is the real Robert Burns here, in our collection of images, and will he please stand up?

This is our main image of Burns, isn’t it? It has become the most popular and the most often copied, perhaps because its original creator, Alexander Naysmith, was a famous painter and his images were well known and seen. However, while Naysmith was well acquainted with Burns, has he perhaps idealised his friend in this image? Robert Burns in the Naysmith style is handsome, perhaps even slightly ‘pretty’, with slim features and fashionable dress. While the Scottish countryside evokes Burns’s farming background, the muck and pleiter of farming life seems absent in this Edinburgh painting.

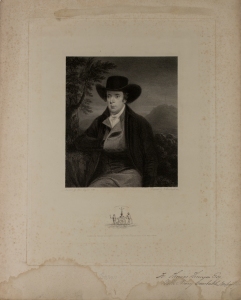

There are other paintings of Robert Burns done by people who knew him and saw him, and they differ substantially. There is the Peter Taylor portrait in our collection here at Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, which shows Burns again in Scottish landscape, still fairly slim, sitting quite formally with a large farmer’s bunnet, but with none of the refined air of Naysmith. Sir Walter Scott, who had met Robert Burns, said of the portrait that ‘I would not hesitate to recognise this portrait as a striking resemblance of the Poet.’

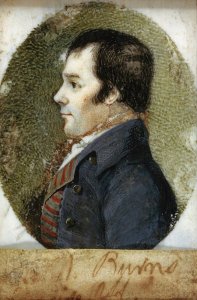

Alexander Reid, 1796

On loan from the Scottish National Portrait Gallery

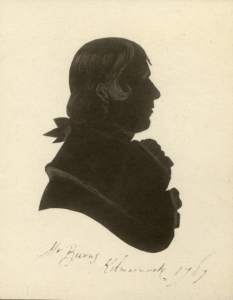

Then, to confuse us further, there is also the Alexander Reid miniature of Burns. This shows him fairly swarthy in face and with a sturdier figure. Yet this portrait was painted only 6 months prior to Burns’s death, at which point he was often described as looking visibly ill and worn. Nonetheless, Burns himself said that this portrait was the best likeness of him that had been taken, and the thicker figure also seems to match with silhouettes taken at the time.

So who is the real Robert Burns? Is it the slender man gazing across the ethereal landscape? Is it the sturdy farmer with ruddy cheeks? Or are these depictions merely focusing on specific aspects of the man, perhaps adapting his image to portray him as they saw him, or wished to see him? The romantic poet, the Ayrshire farmer, the common man, the heaven taught ploughman, the lover, the debater, are all different sides of the real face of Burns.

So come along to the Real Face of Burns and discover old and new ways of seeing Robert Burns! Exhibition opens February 21st at the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum.

The Literary Landscape in Russian Art

On the evening of Thursday 9th October, the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum unveiled its latest temporary exhibition. Conceived jointly by RBBM’s former Director Nat Edwards and the State-Museum Reserve of A.S Pushkin, ‘The Literary Landscape in Russian Art’ is an exhibition of 38 landscape paintings and original fine art prints by Russian artists who drew on the same landscapes that inspired the writing of the famous Russian poet and author Alexander Pushkin. The works span the decades from the early 20th to the early 21st century, and are on loan to RBBM from the State Memorial Historical-Literary and Natural-Landscape Museum-Reserve of Alexander Pushkin in Mikhailovskoye (Mi-kale-ovshka) as part of the Cross-Cultural Year of Great Britain and Russia.

Many may wonder what connects these two historical figures beyond their shared literary prowess. Although Pushkin and Burns were not quite contemporaries, the Russian was born in 1799 just a few years after the death of our Bard. Both men wrote their first poem at the age of fifteen, both were Freemasons and both died at the tragically young age of 37. They are considered to be Romantic poets, with a strong focus on nature, as well as being humanitarians and believers in equality, and both sailed close to the wind with some of their political works, sparking governmental disapproval and even censorship in the case of Pushkin. Finally, both writers had a significant impact on the literary culture of their respective countries and beyond.

Born in Moscow into nobility, Pushkin went on to produce many works, including his most famous play Boris Godunov and his novel in verse Eugene Onegin, later the inspiration for an opera by noted Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The unusual rhyme scheme used in this work has been termed the ‘Onegin Stanza’ or the ‘Pushkin Sonnet’, paralleling the Standard Habbie verse preferred by Robert Burns and often called the ‘Burns Stanza’, which showcases the respective literary influence of these two great writers.

There is also a long standing link between Robert Burns and Russia, and arguably Russian interest in our Bard was initiated by Pushkin, who was himself an admirer of Burns’s work. Translations of Burns’s works into Russian by a series of notable translators, particularly Samuil Marshak (1887-1964) also helped popularise his works in Russia, and in 1956 the Soviet Union was the first country in the world to feature Burns on a postage stamp.

The exhibition will be running at the museum until February and entry is free. We hope you will be able to pay us a visit, and take advantage of this rare opportunity to see these artworks outside of their native country. Why not let us know your favourite in the comments section?

With thanks to: Georgy Vasilevich (Director of the Pushkin Museum), Alyona Boitsova, Vyacheslav Kozmin, Darya Plotnikova, Olga Sandalyuk, Tatiana Morozova, Pavel Tereschenko, Nat Edwards, David Hopes, Chris Waddell, Sean McGlashan and Gavin Pettigrew for all their work in organizing this fantastic exhibition.