Agnes MacLehose

Four Women Who Inspired Burns

In honour of Women’s History Month, throughout March the RBBM Facebook and Twitter have shared poems linked to influential women in Robert Burns’s life. We thought we’d round off the month with a blog exploring each of these ladies in more detail!

First up is Jean Armour, Robert’s wife. She was born 25th February 1765 in Mauchline, Ayrshire. Whilst growing up, Jean was renowned for her beauty and was part of a group of young women often referred to as ‘the Belles of Mauchline’. She met Robert when she was around eighteen, and less than two years later she was pregnant with his child – her father famously fainted when told that Robert was the father! He refused to allow the couple to marry – this meant he would rather Jean be a single mother than married to Robert, which speaks volumes about Robert’s reputation!

Despite this less than promising start to their relationship, Jean and Robert were formally married on 5th August 1788 – Jean’s father had come round to the idea after Robert’s poetry success. They had a mostly happy marriage, despite Robert’s famous infidelities – Jean herself said that he should have had ‘twa wives’.

Jean and her family moved to Dumfries in 1791 and this is where Robert died in 1796. Jean could not attend his funeral as she was in labour with their ninth child, Maxwell. Tragically, Maxwell died at the age of two – just four of the couple’s children survived to adulthood. However, Jean did also look after Betty Park (Robert’s child to Ann Park) and they had a good relationship. After Robert’s death, Jean never remarried, and she lived in the house they had shared in Dumfries until she died 26th March 1834 – she outlived her husband by thirty-eight years.

Next is Agnes Burnes, née Broun – the Bard’s mother. Agnes was born 17th March 1732 near Kirkoswald in Ayrshire. Her mother died when she was just ten years old; being the eldest sibling, it was then Agnes’s responsibility to care for the family until her father remarried two years later. However, Agnes and her new step-mother did not get on well, and Agnes was sent to live with her maternal grandmother in Maybole. She instilled in Agnes a great love for Scottish folk song and music.

Agnes met William Burnes (spelled differently but pronounced the same as ‘Burns’) in 1756 and they married on 3rd December 1757. They settled in the clay biggin William had built in Alloway; Robert Burns was the eldest of their seven children. It is thought that Agnes was a great influence on Robert’s own love of Scottish folk song and music, just as her grandmother had been to her. After William died in 1784, Agnes went to live with her son Gilbert. She moved around with his family until her death, at the age of eighty-seven, on 14th January 1820.

The third woman we featured this month is Frances Dunlop, a wealthy heiress almost thirty years older than Burns. Born 16th April 1730, her maiden name was Wallace, and her family claimed descent from William Wallace himself! Frances married at eighteen, when her husband, John Dunlop, was in his forties. They had a happy life together – however, John died in 1785. In the same year, Frances’s childhood home and lands were lost to the family. These incidents caused her humongous grief and she fell into a prolonged depression.

What finally roused her was Robert Burns’s poem ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’. She enjoyed reading it so much that she contacted Robert to ask for more copies and to invite him to her home – this began a long and friendly correspondence that lasted until the end of Robert’s life. Frances treated him almost like another son, praising his achievements and admonishing his indiscretions. She even offered advice on drafts of poetry and songs he would send her, the most famous of these being ‘Auld Lang Syne’! Although there was a two-year gap in their correspondence after Burns had offended Frances with some comments she deemed radical, Frances sent him a reconciliatory letter mere days before Robert’s death. She outlived him by nearly twenty years, dying 24th May 1815.

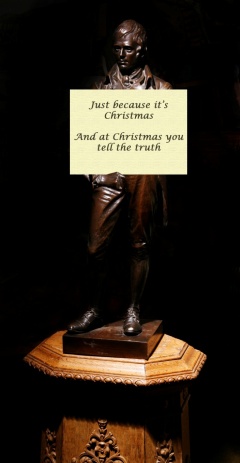

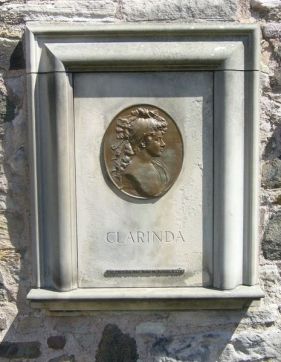

The last woman featured is Agnes Maclehose, aka the ‘Clarinda’ to Burns’s ‘Sylvander’. Agnes was born 26th April 1758 in Glasgow. She grew up to be a very articulate, well-educated and beautiful woman. She married at eighteen, but the marriage was an unhappy one and she separated from her husband in 1780.

Agnes met Robert Burns several years later at a party in Edinburgh – they were immediately taken with each other, and she wrote to him to invite him to tea at her home. Although an accident prevented this from happening, there began a long series of love letters and love poetry sent between the two. They used the pseudonyms ‘Clarinda’ and ‘Sylvander’. Despite the intensity of their correspondence, it is widely-thought that their affair was unconsummated. As Agnes was an incredibly pious woman and, although separated, still married, this makes sense.

In 1791 Agnes sailed for Jamaica to attempt to reconcile with her husband – however, he had started a family with another woman, so she returned to Scotland after only a few months. She met Robert for the last time in December of that year. For the rest of her life Agnes took great care of her letters from Robert, and after his death she even negotiated to have the letters she had sent to him returned to her.

In 1821 Agnes had tea with Jean Armour in Edinburgh. The two women, who could have been viewed as rivals of sorts, got on well and talked at length about their families, as well as their shared regard for Robert Burns. Agnes died twenty years later, at the age of eighty-three, on 23rd October 1841.

You can find the original Facebook and Twitter posts at https://www.facebook.com/RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum/ and https://twitter.com/RobertBurnsNTS.

Wardrobe Secrets: 6 Facts about 18th Century Female Fashion

Alexander Banks, Artist; John Miers, Artist

While many women in Robert Burns’s life came from the same poor and rural background as he did, one lady he fell in love with came from a much higher social strata. This lady was Agnes McLehose, (or Clarinda, as Burns called her). Agnes was part of the capital’s wealthy society and, through this; she met our bard in 1887. But what did the high class ladies of Burn’s lifetime look like? Here we have 6 unusual facts that lie behind 18th century female fashions!

1) No pants.

In the 18th century ladies might wear a long chemise, a corset, and then layers of petticoats, but no pants would feature in this ensemble of undergarments. Pants for women do not come in until the early 19th century, and even then they are split at the crotch, and tied at the waist: hence why we say ‘pair of pants.’

2) Mouse skin eyebrows.

Timorous beasties! It was fashionable for ladies to glue eyebrows made of mouse skin to their forehead. Why? This was largely due to make up practises at the time causing hair loss, which leads to fun fact number three:

3) Lead white paint

Ever wished to have that wonderful contrast between white skin and blushing cheeks? Well ladies would have achieved it by daubing white lead paint onto their faces, followed by red carmine (also containing lead). While this might have given you a temporary beautiful complexion, it would also have slowly poisoned you and perhaps led to hair loss.

4) Dimity Pockets

Pockets sewn into clothing arrive late in history. In the medieval period, people would string their bags and pouches from their belts. By this time in history, however, pockets for ladies were separate, and had ties attached so they could fasten them under their dress and around their waist.

5) Wigs

Powdered wigs became very fashionable in this period, for both men and women. Marie Antoinette would become very famous for her towering ‘pouffe’ (said at one point to have reached a height of 6ft!). For those who could afford these wigs, they had to be treated with care, while particularly huge wigs would involve sleeping upright with two or three pillows.

6) Teeth

Where’er that place be priests ca’ hell,

Where a’ the tones o’ misery yell,

An’ ranked plagues their numbers tell,

In dreadfu’ raw,

Thou, Toothache, surely bear’st the bell,

Amang them a’!

Address to a Toothache

Toothache was an unwanted visitor for rich and poor alike, with figures, such as George Washington, known for their fake teeth! So our ladies of the 18th century would probably hide behind a fan rather than flash their pearly whites. If you could afford it, you could buy Ivory dentures, but those often rotted quickly leaving a bad smell.

1860

W. H. Midwood

So behind the silks and embroidered dresses, it is clear that our 18th century ladies have a lot they keep hidden! As to whether Clarinda ever sported a ‘pouffe’ wig, or daubed on white paint for the perfect complexion, we will never really know. Sadly, aside from a silhouette, there are no contemporary paintings, or anything remaining from her wardrobe. Yet, by looking at the secrets on the 18th century wardrobe, we can create a picture of what Edinburgh ladies might have looked like in the time of Robert Burns.

WHAT DOES YOUR CUP SAY ABOUT YOU!

Tea or Coffee? The question is simple but can evoke strong opinions from people. Likewise people can have strong connections and feelings to the cup they choose to use. Here in the RBBM education office we are mixed tea and coffee drinkers, but our cups are very different: some have polar bears, others star signs – mine is a purple donkey!

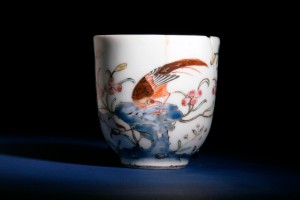

In our museum collection we have Agnes ‘Clarinda’ McLehose’s coffee cup and Jean Armour’s tea cup and saucer. These two objects stuck with me, and when I thought of the objects side by side, I began to draw comparisons between the design, liquid, and ultimately, the two women who were big personalities in Robert’s life. What did the cup say about them? I began to think through the drink and cup and create an image of these women in my head.

Tea and coffee were both expensive drinks in the eighteenth century. Coffee was consumed in Coffee Houses, which were hubs for the discussion of trade and politics; while tea was far more gentile and social, and employed a whole set delicate paraphernalia. Also, by 1785 tea was far more affordable than it had been previously -this was due to the Government slashing duty on tea to reduce smuggling.

Clarinda is already looking a wee bit adventurous… and exotic? While Jean, the gentle ‘wife’ is more feminine with her tea!

Jean’s tea cup and matching saucer is white with a red floral decoration. The cup and saucer appears sturdy and reliable, even today there are little signs of damage or tea staining! A frequent problem in break room mugs… The flower decor is pretty but it looks tough and enduring like it would survive storms and frosts. For me it speaks to the fact that Jean stuck with Robert through thick and thin!

By comparison Clarinda’s coffee cup is far more exotic, But then Clarinda was exotic, she was part of the upper classes and literati of Edinburgh, a far cry from Jean in the countryside. Her cup is refined and dainty, porcelain with the Chinese Pheasant; a symbol of beauty and good fortune, also the representation of literary refinement.

The imagery behind the cups brought to life for me parts of their characters and personalities, giving us hints about the two main women in Roberts’s life.

In the end I love the delicate design of Clarinda’s coffee cup, but I am a tea drinker at heart….

Burns’s Love Story

Robert Burns has written many different love poems, and beautiful songs, but what has been his inspiration for such poems and songs?

Well to start us off on this journey through the extensive love life of our Robert Burns, you should probably know that Robert was no saint when it came to the affairs of the heart, he went from woman to woman and relationship to relationship to find his perfect bonnie lass.

At the beginning of his path through the mysteries of the opposite sex there was Nellie, she was considered to be the first girl he ever fell for and certainly not the last but she started him off on the road of love and romance. Robert was only fifteen when he met Nell and he wrote a song for her called ‘Handsome Nell’.

O Once I lov’d a bonnie lass,

An’ aye I love her still,

An’ whilst that virtue warms my breast,

I’ll love my handsome Nell.

As bonnie lasses I hae seen,

And mony full as braw;

But for a modest gracefu’ mein,

The like I never saw.

A bonny lass I will confess,

Is pleasant to the e’e,

But without some better qualities

She’s no a lass for me.

But Nelly’s looks are blythe and sweet,

And what is best of a’,

Her reputation is compleat,

And fair without a flaw;

She dresses ay sae clean and neat,

Both decent and genteel;

And then there’s something in her gait

Gars ony dress look weel.

A gaudy dress and gentle air

May slightly touch the heart,

But it’s innocence and modesty

That polishes the dart.

‘Tis this in Nelly pleases me,

‘Tis this enchants my soul;

For absolutely in my breast

She reigns without controul.

This song was believed to have been written in 1774 and speaks of feminine grace and innocence. This girl was the one that started Robert’s fascination with the opposite sex.

No doubt that Robert had several different women in his life between Nell and his courtships to Jean Armour, however there are only records of the more influential on his romantic radar. Jean Armour was the lucky lass that Robert eventually settled down with and married, however it was not all happy, as at first it was just a fling together in 1785, but then Jean fell pregnant to Robert. She was then taken away to Paisley by her father to prevent her from being with Robert but was later called to admit that she bore an illegitimate child to Robert, from that point Robert and Jean began to court.

The story of the Ayrshire rascal does not end here however, he then met ‘Highland Mary’ later in 1785 and Robert fell for her head over heels instantly. He wrote a song for her called ‘The Highland Lassie’

Nae gentle dames tho’ ne’er sae fair

Shall ever be my Muse’s care;

Their titles a’ are empty show,

Gie me my Highland Lassie, O.

Within the glen sae bushy, O,

Aboon the plain sae rashy, O,

I set me down wi’ right gude will

To sing my Highland Lassie, O.

O were yon hills and vallies mine,

Yon palace and yon gardens fine;

The world then the love should know

I bear my Highland Lassie, O.-

But fickle Fortune frowns on me,

And I maun cross the raging sea;

But while my crimson currents flow,

I love my Highland Lassie, O.-

Altho’ thro’ foreign climes I range,

I know her heart will never change;

For her bosom burns with honor’s glow,

My faithful Highland Lassie, O-

For her I’ll dare the billow’s roar;

For her I’ll trace a distant shore;

That Indian wealth may lustre throw

Around my Highland Lassie, O.-

She has my heart, she has my hand,

By secret Truth and Honor’s band:

Till the mortal stroke shall lay me low,

I’m thine, my Highland Lassie, O.-

Robert loved this woman with his heart and soul, he asked her to elope with him to Jamaica, and she had intended to but alas it was not meant to be, she died in 1786 after falling seriously ill. However, before she died she and Robert had exchanged Bibles, and it was said that they may also have exchanged vows; however no conclusive evidence exists to prove this is correct. So Robert returned to his lass Jean Armour to continue courtship.

The next woman I am going to talk about is Agnes McLehose, but before I do I should comment on how Robert was supposed to be courting Jean Armour at the time while he was sending letters and visiting Agnes. Agnes had previously been married before she met Burns, and although her and her husband were separated, she was technically still married and so she still upheld her vows, and never touched another man.

Robert met Agnes in 1787 while in Edinburgh on publishing business. He quickly discovered that Agnes was a lover of poems and different writings which interested Robert. Agnes and Robert started to write to one another, but not long after Robert was involved in a carriage accident and was bed ridden for a short time. They exchanged many letters which became more intense and intimate as time progressed. Robert would talk of Jean Armour behind her back saying that he could not stand her, and he found her disgusting compared to Agnes, and Agnes would talk of her situation in being a married woman but wanting to be with Robert (some of these letters are in our museum http://www.burnsmuseum.org.uk/collections). After a while they began to exchange visits, this is where their relationship turned sour as Robert wanted to be with Agnes completely but Agnes could not forget her vows which tied her. Not too long after, Robert looked to other woman around him, one such being a servant girl of Agnes’ who bore a child for Robert. From that point on it was over, Robert left her, and she went to seek her husband, whom she found in Jamaica with another woman, who had given him children. So she returned to be with Robert but was too late and he had married Jean Armour.

After Robert’s affair with Highland Mary and Agnes McLehose Robert returned to Jean Armour ready finally to commit himself and in 1788 he married her and was with her until the day he died. Jean Armour gave Robert nine children in total although most of them did not survive very long and died in infancy. He did truly love Jean Armour in the end and was happy with her as a wife.

And so the tale of Roberts’s love life seemed like a never ending story of tragedy and romance, not to mention a lot of beautiful young ladies but in the end he never could live without his Jean that stole his heart.

By Fiona Jones

Volunteer Learning Assistant

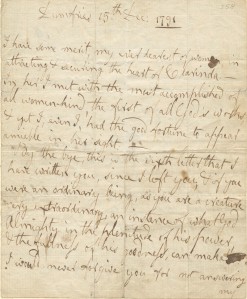

In 1787 Robert Burns spent the Christmas period exchanging letters with Agnes MacLehose. Their new love affair was unfolding, with Agnes revealing her unhappy marriage and their agreement to take the Arcadian names of Sylvander and Clarinda.

On 28th December Robert Burns made an unsuitable outpouring of love and was fairly insincere in his contrition over Agnes’ or perhaps a more disapproving audience’s imagined displeasure:

I do love you if possible better for having so fine a taste and turn for Poesy.

I have again gone wrong in my usual unguarded way, but you may erase the word, and put esteem, respect, or any other tame Dutch expression you please in its place.

I like to think of this as significant within a certain genre of love declarations, not because of his indiscretion but the time of year in which he made it. It is the Christmas-inspired ill-advised declaration of love, made recognisable by a Christmas film that is almost unavoidable at this time of year; Richard Curtis’s Love Actually. OK, so perhaps such slushy Christmas spirit wasn’t something so commonly encountered in 18th Century Scotland as it is now, but it’s an amorous story fraught with the problems worthy of a scene in one of our favourite Christmas films nonetheless.

Merry Christmas!