history

Fragments

Two memorialising students from the University of Glasgow Scottish Literature department visited the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum recently to do research and blog-writing as part of their course. The following blog was researched and written by Struan McCorrisken.

Two objects in particular represent a curious facet of the cult of Burns, that is the accumulation and preservation of any and all tangible aspects of the Bards’ life. A fragment, no more than the size of a matchbox, of Jean Armour and Robert Burns’ marital bed, is encased in a large wooden discus and visible beneath a glass plate. The other is a small board containing two strips of material roughly large enough to make a small sock out of. The black silk is merely silk; and the piece of wood, just wood. What truly matters is the association these objects possess; an aspect so powerful it has driven them to be curated and displayed despite being only tiny fragments of the original whole.

This sort of collecting exemplifies precisely why these objects are valuable. Not the objects themselves, but the connection to the past they offer, the prospect of tangibility that they represent. The type of collecting and commemoration that Burns undergoes is similar almost to that of a medieval saint. This sort of fervent reverence began very soon after Burns’ death, and we may well consider it a sign that Calvinist Scotland, devoid of pomp and pageantry through the stifling presence of the Kirk and the absence of the king, was looking for something to fill the gap. This perhaps was a search for joyful veneration of a figure beyond the austere auspices of the Kirk. Burns’ own rebellious stance against much of the Kirk’s posturing may have added to that attraction. While the comparison of Burns to a saint may sound fanciful, but it’s worth considering how saints are venerated. They are commemorated with talismans, awards and honours are given in their names, statues are erected at places they had a connection to, and they have specific symbols and icons associated with them. Some have specific days they are venerated on, or specific shrines dedicated to them. We certainly manufacture talismans of Burns, as any glance around a Scottish gift shop reveals. There are awards in his name, such as the Robert Burns Humanitarian Award, and a multitude of organisations associated with him. Scotland is replete with statues and plaques of Burns, miniature shrines almost, at places associated with his life and the lives of those associated with him. Images such as the mouse, the plough and the rose are associated with Burns, arguably his very own attributes. He certainly has his own day, and the proposed desire for ritual in the Scots certainly comes to the fore here, reinforced heartily by Walter Scott’s own contributions to images of Scottish culture (tartan, kilts etc). We eat food associated with Burns and toast his “immortal memory”. Items from his life, however fragmentary, are collected and displayed in museums. A new form of reliquary perhaps?

Indeed, it may be postulated that Burns is a new form of saint for a modern, more secular, Scotland. A person of great achievement whom we admire, commemorate, and attempt to emulate. A part of this commemoration is undoubtedly the use of objects, in any condition, to help us connect with the man, long since passed.

Celebrating Scots Language

As today is International Mother Language Day, our blog post explores the history of Scots language to celebrate and promote Scottish linguistic heritage.

Scots is descended from a form of Anglo-Saxon brought to the south-east of present day Scotland by the Angles (Germanic-speaking peoples) around AD 600. The video below, from The University of Edinburgh, illustrates the origins of Scots language.

Like many European countries, early Scots speakers primarily used Latin for official and literary purposes. The earliest surviving written poem in Scots, dated to 1300, is a short lyric on the death of King Alexander III (ruled 1249-1286) which appeared in Andrew Wyntoun’s work entitled The Original Chronicle:

“Qwhen Alexander our kynge was dede, That Scotland lede in lauch and le, Away was sons of alle and brede, Off wyne and wax, of gamyn and gle. Our golde was changit into lede. Crist, borne into virgynyte, Succoure Scotland and ramede, That is stade in perplexitie”.

Yet, the first Scots poem of any length called The Brus by John Barbour was recorded in 1375. Composed under the patronage of Robert II, this poem’s tale follows the actions of Robert the Bruce through the first war of independence.

The History of Scots from the 14th– 18th Century

Between the 14th and 16th century, writing in the vernacular thrived during the reigns of James III (ruled 1460-1488) and James IV (ruled 1488-1513): Scots language truly came into its own. This period’s Scots poets are known as medieval makars or master poets, after William Dunbar’s the Lament for the Makaris, for the great literacy culture that was produced in lowland Scotland. Dunbar was a virtuosic poet with an impressive range, varying from elaborate religious hymns to scurrilous bawdy verse.

Also a makar, King James VI (ruled 1567-1625) laid down a standard writers were expected to follow in his essay on literary theory entitled The Reulis and Cautellis. However, after James VI also became James I of England in 1603, Scots language and makars were no longer supported by the Royal Court. Pre-1603, James VI voiced the differences between English and Scots but now, as ruler of the British Empire, he attempted to Anglicise Scottish society for cultural, linguistic and political union of his kingdoms. Herein, the literary activity of 17th century Scots poets declined as many, like William Drummond of Hawthornden, decided to write in English instead. This change of language was encouraged by the Royal Court alongside the larger and more lucrative English publishing markets. In Scotland, all classes continued to write and speak in Scots but, for publications writers had their texts ‘Englished’.

The Great Scots Poets of the 18th Century

In the 18th century, under the 1707 Treaty of Union, Scotland joined England to form the new state of Great Britain and poets began to utilise an increasingly bilingual literary situation. Poets combined Augustan English poetry with Scots songs, tales and older poems to create a vernacular revival in Scots verse. The work of poets such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns demonstrated the popularity and poetic nature of Scots as a literature. These poets, expressing a national identity, produced poems that were, and continue to be, widely read.

Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) was born in Lanarkshire and educated at Crawfordmoor Parish School. Following his mother’s death, Ramsay moved to Edinburgh to study wig-making and eventually opened a shop near Grassmarket. He was an eminent portrait painter and began writing poetry from the early 1700s. In 1721, Ramsay published his first volume as a blend of English language and Scots poems. He abandoned the wig-making trade to become a bookseller, opening a shop near Edinburgh’s Luckenbooths- this also became Britain’s first circulating library. Ramsay’s works, such as Tea-Table Miscellany (1724), The Ever Green (1724) and The Gentle Shepard (1725), laid the foundations for Scot writers like Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns.

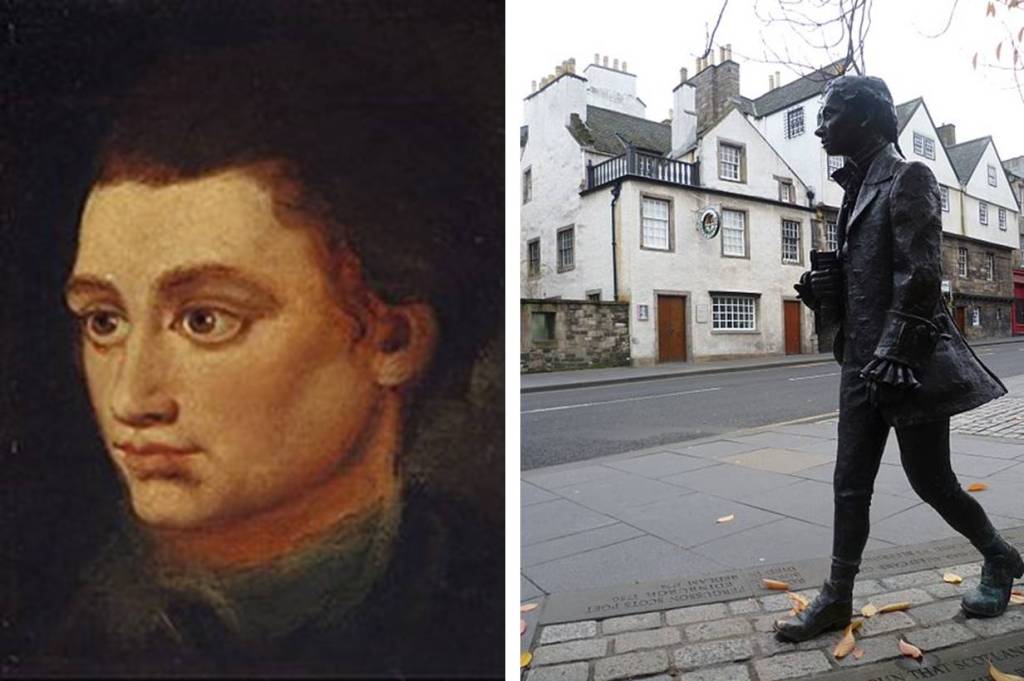

Robert Fergusson (1750-1774) was born in Edinburgh’s Old Town to Aberdeenshire parents. He attended St. Andrews University and became infamous for his pranks- for which he came close to expulsion. In 1771, Fergusson anonymously published his first trio of pastorals entitled Morning, Noon and Night. He amassed an exquisite range of about 100 poems, developing existing literary forms and contributing to contemporary debate. Aged 24, Fergusson experienced a fatal blow to his head falling down a flight of stairs, he was deemed ‘insensible’ and transferred to Edinburgh’s Bedlam madhouse where he later died. In 1787, Robert Burns erected a monument at his grave, commemorating Fergusson as ‘Scotia’s Poet’.

Robert Burns called Fergusson “my elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in muse”. Clearly inspired by the poet, Burns adopted both Fergusson and Ramsay’s use of Scots words and verse to master his own poetry and advance Scots literature. In doing this, Burns became Scots language’s most recognised voice with poems and songs read and sung worldwide. The Robert Burns Birthplace Museum displays volumes and poems by Fergusson and Ramsay (below), highlighting the similarities to Burns’ work in terms of tone, format, subject matter and, of course, Scots language.

The History of Scots Post-Burns to the Present

In the 19th century, building on the work of Scots poets, novelist began combining English and Scots in their writings. More often, English was used for the main narrative and Scots voiced Scots-speaking characters or short stories.

After this period, the 20th century saw a radical renaissance of Scots poetry, primarily through Hugh MacDiarmid (pen name of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid’s work The Scottish Chapbook, reassessed early Scots verse by using words from across different regions. Later, Edinburgh poet Robert Garioch reopened links to the Scots verse MacDiarmid devalued. Garioch, to a greater extent than MacDiarmid, developed a form of Scots united to any particular locality and produced a model that future writers could follow. Other 20th century poets, included Edwin Morgan, and his translation of Vladmir Mayakovsky’s poetry into Scots, as well as Tom Leonard’s Six Glasgow Poems.

Today, Scots language continues to thrive. In communities across Scotland, people use Scots as a language to write and speak. As the 2011 Scottish Census reported, there are 1.5 million speakers of Scots within Scotland, which is around 30% of the population.

So, why not challenge yourself? And join them? To celebrate Scots language and International Mother Language Day, learn a new word or a new phrase or more!

Check out the links below for more ways to learn Scots:

- On social media, we run a Scots word of the week campaign, encouraging our followers to guess and discuss what they mean. We often get international audiences commenting on the similarities between Scots and various European languages. Check it out on Facebook (@RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum) and Twitter (@RobertBurnsNTS).

- Search our blog for Scots language posts: https://burnsmuseum.wordpress.com/tag/scots-language/

- For Scots on Twitter, take a look at these pages: @lairnscots, @scotslanguage, @ScotsScriever, @tracyanneharvey @rabwilson1 and @TheScotsCafe.

- Join the Open University’s FREE online Scots language and culture course: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705

- Or, check out some of these websites: https://www.scotslanguage.com/

https://www.gov.scot/policies/languages/scots/

http://www.cs.stir.ac.uk/~kjt/general/scots.html

https://education.gov.scot/improvement/Documents/ScotsLanguageinCfEAug17.pdf

Gang oan, gie it an ettle!

The First Burns Supper and Beyond!

With Burns Night approaching, let’s delve in to the origins of the very first Burns Supper in Alloway, and how this grew into the global Burns Suppers held today!

The first Burns Supper was held in July 1801 at the Burns Cottage in Alloway, five years after Burns’ death. Led by Freemason Reverend Hamilton Paul, it was an informal affair between a small gathering of his fellow freemasons. Burns was also part of the Freemasons at Tarbolton, which allowed him to form a large network of friends and acquaintances, and the nine men present at the first Burns Supper were closely connected with him. This first supper was a toast to Burns’ life, and the men recited his most lively works to symbolise his exciting and accomplished legacy as a bard. They considered the first supper a huge success, and arranged to hold a second Burns Supper for his birthday in January. From this the tradition of the Burns Supper began.

At this time Clubs, where (usually) men met regularly to eat, drink and socialise, were well established, and so the format of the Burns Supper lent itself well to this popular style of social gathering in Scotland. At the first Burns Supper ‘To a Haggis’ was read before the haggis was eaten and several rounds of toasts were given; these key rituals have remained the integral components of Burns Suppers throughout the years. Hamilton Paul’s interpretation of these most important elements of Burns’ work and life allowed for the supper format to be easily adapted to other sites out-with the Burns Cottage.

According to writer Clark McGinn the Burns Supper evolved through two phases; the charismatic period and the traditional period. The charismatic period began from the first Burns Supper, and includes the more informal suppers between those directly connected to Burns, or Ayrshire. These were taken on by members of literary clubs in particular.

In Burns’ Day, the literary scene was close-knit and active in meeting at clubs and other occasions. This must have greatly accelerated the popularity of Burns Suppers as these passionate literary fans and writers were proactive in gathering regularly, spreading the idea across Scotland. Spontaneous Burns Suppers began to be held across Ayrshire, and eventually in other parts of Scotland.

Although informal to begin with, they gradually became more regulated and standardised, with stricter rules regarding the format as those outside of Burns’ circles and even Ayrshire circles became involved. The first Burns Supper held in Edinburgh in 1815 was alike to the informal suppers held in clubs across Ayrshire, however the supper for the following year was presented as a formal public dinner, to be held every three years. Attended by Sir Walter Scott, the 1816 Burns Supper pledged to give Robert Burns the honorary tribute he deserved, and so magnificence and splendour were at the forefront of the event. This marked the transition into the traditional period of the Burns Supper format.

What had started out as a Burns Supper had grown into bigger and grander events, which helped Burns’ popularity all over the country intensify. Burns Suppers held in London in the early 1800s introduced the idea to a wider audience, and they were also appearing in India, Australia and America. The traditional period continued throughout the Victorian era, which saw the Burns Festival Procession of 1844 in Alloway and the Burns Federation established in 1885. The Burns Federation sought to unite all of the Burns Clubs across the world, and still exists today as a common link for Burns fans globally.

Today Burns Supper celebrations continue all over the world, from the Cottage where the first Supper was held, all the way to Canada and New Zealand. The toast to the haggis is still a key feature of the Burns Supper, and all of the traditions of the first Supper have remained important throughout the years. For Burns Night 2020 we have lots of exciting events on the 25th and 26th of January at the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, we hope to see you there!

By Kirsty Reid, Learning Trainee

Further Reading: ‘The Burns Supper: A Comprehensive History’, by Clark McGinn

Bards, Burns an Blether in The Bachelors’

It’s owre twa hunner year syne The Bachelors’ Club in Tarbolton saw the young Robert Burns an his cronies speirin aboot the issues o thaur day. It is therefore a braw honour tae gie this historic biggin a heize ainst mair by bein involved in organisin and hostin monthly spoken word an music nichts in the place whaur Robert Burns fordered his poetic genius, charisma an flair fir debate.

The Bachelors’ Club nichts stairtit in March this year eftir Robert Burns Birthplace Museum volunteer Hugh Farrell envisaged the success of sic nichts in sic an inspirational setting.

Tuesday the third o September saw the eighth session, an it wis wan we will aye hae mind o. Wullie Dick wis oor compère as folk favoured the company wi a turn.

Oor headliner wis Ciaran McGhee, singer, bard an musician. Ciaran bides an works in Embra an I first shook his haun some twa year syne at New Cumnock Burns Club’s annual Scots verse nicht. The company wis impressed then an agin at the annual “smoker” an at a forder Scots verse nicht. Ciaran traivelled doon tae Ayrshire tae play fir us, despite haen jist duin a 52 show marathon owre the duration o Embra festival.

Ciaran stertit wi a roarin rendition o “A Man’s a Man for a That”, an we hud a blether aboot hoo this song is as relevant noo, in these days o inequality an political carnage, as it wis twa hunner year syne, a fine example o Burns genius an insicht. Ciaran follaed wi Hamish Imlach’s birsie “Black is the Colour”, the raw emotion gien us aa goosebumps!! Ciaran also performed Johnny Cash’s cantie “Folsom Prison Blues”, an then Richard Thomson’s classic “Beeswing”, a version sae bonnie it left us hert-sair! Ciaran also performed tracks fae his album “Don’t give up the Day Job”.

The company wir then entertained by Burns recitals an poetry readins fae a wheen o bards an raconteurs. A big hertie chiel recited “The Holy Fair”, speirin wi the company on hoo excitin this maun hae buin in Burns day, amaist lik today’s “T in the Park”.

We hud “Tam the Bunnet” a hilarious parody o Tam o Shanter an Hugh Farrell telt us aboot the dochters ca’ad Elizabeth born tae Burns by different mithers, Burn’s first born bein “Dear bocht Bess”, her mither servant lass Bess Paton. Later oan cam Elizabeth Park, Anna Park’s dochter, reart by Jean Armour, an thaur wis wee Elizabeth Riddell, Robert an Jean’s youngest dochter wha deid aged jist 3 year auld. A “Farrell factoid” we learned wis that in Burns day, if a wee lassie wis born within mairrage, she was ca’ad fir her grandmither, if she wis born oot o wedlock she taen her mither’s first name. Hugh recited “A Poet’s Welcome To His Love-Begotten Daughter” fir us, the tender poem Burns scrievit, lamentin his love fir his first born wean, Elizabeth Paton.

We hud spoken word by various bards on sic diverse topics as a hen doo, a sardonic account o an ex girlfriend’s political tendencies, an a couthie poem inspired by a portrait o a mystery wummin sketched by the poets faither. In homage tae Burn’s “Poor Mailie’s Elegy”, we hud a lament in rhyme scrievit in the Scots leid, featurin the poet’s pet hen.

We learned o the poetess Janet Little, born in the same year as Burns, who selt owre fowre hunner copies o the book o her poetry she scrievit. This wummin wis kent as “The Scotch Milkmaid” an wis connected tae Burn’s freen an patron, Mrs Frances Anna Dunlop.

We also learned o hoo Burns wis spurned by Wilhelmina Alexander, “The Bonnie Lass of Ballochmyle” an hoo, eftir her daith, she wis foun tae hae kept a copy o the poem Burns scrievit fir her.

We hud mair hertie music fae Burness, performin Burns an Scottish songs sic as “Ye Jacobites by Name” an a contemporary version o “Auld Lang Syne” wi words added by Eddie Reader tae an auld Hebrew tune.

We hud “Caledonia” an “Ca the Yowes tae the Knowes” sung beautifully by a sonsie Auchinleck lass wha recently performed it at Lapraik festival in Muirkirk (oan Tibby’s Brig nae less!).

The newly appointed female president o Prestwick Burns Club entertained us on her ukelele wi the Burns song “The Gairdner wi his Paiddle” itherwise kent as “When Rosie May Comes in with Flowers”.

At the hinneren wi hud a sing alang tae Seamus Kennedy’s “The Little Fly” on the guitar an Ciaran feenished wi “Ae Fond Kiss”, interrupted by his mammy wha phoned tae see when he wis comin haim tae New Cumnock!

We hud sae muckle talent in The Bachelors’, that we didnae hae time fir a’body to dae a turn, so thaim that didnae will be first up neist time.

A hertie thanks tae a the crooners, bards an raconteurs an tae a’body in the audience fir gien up thaur time, sharin thaur talent an ken an gien sillar tae The Bachelors’ fund. Sae faur we hae roused £862 which hus been paid intae the account fir the keepin o The Bachelors’ Club.

Hugh Farrell is repeatin history by stertin a debatin group in The Bachelors’ on Monday 11th November, 239 year tae the day syne Burns launched it first time roon. Thaur will be a wee chainge tae the rules hooever, ye dinnae hae tae be a Bachelor an ye dinnae need tae be a man tae tak pairt!!

The Bachelors’ sessions are oan the 1st Tuesday o every month 7pm tae 10.30pm an a’body wi an enthusiasm for Burns is welcome.

Scrievit by Tracy Harvey, Resident Scots Scriever fir RBBM

Four Women Who Inspired Burns

In honour of Women’s History Month, throughout March the RBBM Facebook and Twitter have shared poems linked to influential women in Robert Burns’s life. We thought we’d round off the month with a blog exploring each of these ladies in more detail!

First up is Jean Armour, Robert’s wife. She was born 25th February 1765 in Mauchline, Ayrshire. Whilst growing up, Jean was renowned for her beauty and was part of a group of young women often referred to as ‘the Belles of Mauchline’. She met Robert when she was around eighteen, and less than two years later she was pregnant with his child – her father famously fainted when told that Robert was the father! He refused to allow the couple to marry – this meant he would rather Jean be a single mother than married to Robert, which speaks volumes about Robert’s reputation!

Despite this less than promising start to their relationship, Jean and Robert were formally married on 5th August 1788 – Jean’s father had come round to the idea after Robert’s poetry success. They had a mostly happy marriage, despite Robert’s famous infidelities – Jean herself said that he should have had ‘twa wives’.

Jean and her family moved to Dumfries in 1791 and this is where Robert died in 1796. Jean could not attend his funeral as she was in labour with their ninth child, Maxwell. Tragically, Maxwell died at the age of two – just four of the couple’s children survived to adulthood. However, Jean did also look after Betty Park (Robert’s child to Ann Park) and they had a good relationship. After Robert’s death, Jean never remarried, and she lived in the house they had shared in Dumfries until she died 26th March 1834 – she outlived her husband by thirty-eight years.

Next is Agnes Burnes, née Broun – the Bard’s mother. Agnes was born 17th March 1732 near Kirkoswald in Ayrshire. Her mother died when she was just ten years old; being the eldest sibling, it was then Agnes’s responsibility to care for the family until her father remarried two years later. However, Agnes and her new step-mother did not get on well, and Agnes was sent to live with her maternal grandmother in Maybole. She instilled in Agnes a great love for Scottish folk song and music.

Agnes met William Burnes (spelled differently but pronounced the same as ‘Burns’) in 1756 and they married on 3rd December 1757. They settled in the clay biggin William had built in Alloway; Robert Burns was the eldest of their seven children. It is thought that Agnes was a great influence on Robert’s own love of Scottish folk song and music, just as her grandmother had been to her. After William died in 1784, Agnes went to live with her son Gilbert. She moved around with his family until her death, at the age of eighty-seven, on 14th January 1820.

The third woman we featured this month is Frances Dunlop, a wealthy heiress almost thirty years older than Burns. Born 16th April 1730, her maiden name was Wallace, and her family claimed descent from William Wallace himself! Frances married at eighteen, when her husband, John Dunlop, was in his forties. They had a happy life together – however, John died in 1785. In the same year, Frances’s childhood home and lands were lost to the family. These incidents caused her humongous grief and she fell into a prolonged depression.

What finally roused her was Robert Burns’s poem ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’. She enjoyed reading it so much that she contacted Robert to ask for more copies and to invite him to her home – this began a long and friendly correspondence that lasted until the end of Robert’s life. Frances treated him almost like another son, praising his achievements and admonishing his indiscretions. She even offered advice on drafts of poetry and songs he would send her, the most famous of these being ‘Auld Lang Syne’! Although there was a two-year gap in their correspondence after Burns had offended Frances with some comments she deemed radical, Frances sent him a reconciliatory letter mere days before Robert’s death. She outlived him by nearly twenty years, dying 24th May 1815.

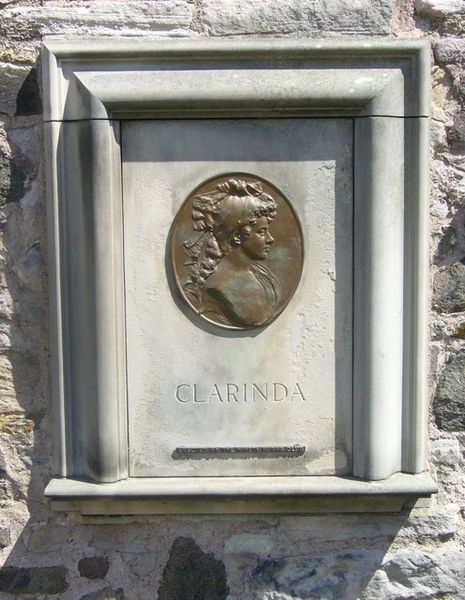

The last woman featured is Agnes Maclehose, aka the ‘Clarinda’ to Burns’s ‘Sylvander’. Agnes was born 26th April 1758 in Glasgow. She grew up to be a very articulate, well-educated and beautiful woman. She married at eighteen, but the marriage was an unhappy one and she separated from her husband in 1780.

Agnes met Robert Burns several years later at a party in Edinburgh – they were immediately taken with each other, and she wrote to him to invite him to tea at her home. Although an accident prevented this from happening, there began a long series of love letters and love poetry sent between the two. They used the pseudonyms ‘Clarinda’ and ‘Sylvander’. Despite the intensity of their correspondence, it is widely-thought that their affair was unconsummated. As Agnes was an incredibly pious woman and, although separated, still married, this makes sense.

In 1791 Agnes sailed for Jamaica to attempt to reconcile with her husband – however, he had started a family with another woman, so she returned to Scotland after only a few months. She met Robert for the last time in December of that year. For the rest of her life Agnes took great care of her letters from Robert, and after his death she even negotiated to have the letters she had sent to him returned to her.

In 1821 Agnes had tea with Jean Armour in Edinburgh. The two women, who could have been viewed as rivals of sorts, got on well and talked at length about their families, as well as their shared regard for Robert Burns. Agnes died twenty years later, at the age of eighty-three, on 23rd October 1841.

You can find the original Facebook and Twitter posts at https://www.facebook.com/RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum/ and https://twitter.com/RobertBurnsNTS.

Burns and his Wumin: The Attitudes to Women Found in Burns’s Poetry

As it’s Women’s History Month, one of the Learning Trainees here at RBBM, Caitlin Walker, has written about the attitudes to women found in Burns’s poetry. She has written the post in a similar way to how she would speak it, which is why there is a mixture of Scots and English language.

Maist folk know that Robert Burns enjoyed the company of women – his famous love affairs, the hundreds of poems and songs they inspired and the thirteen (that we know of!) weans he fathered attest to that. But what did he actually think of women?

Burns was born and lived his life during the latter half of the eighteenth century, a time when women couldnae vote and were rarely, if ever, formally educatit. Gender roles were strictly prescribed – for instance, women of the working class were given no formal education but taught how to run a hoose and look after a faimlie. Tasks were divided by gender completely, to the extent that women milked the coos but men mucked oot the byre, and during harvest time men used the scythe while women used the heuk. Women of higher classes would have learned literacy and maybe even another language or a musical instrument, but the expectation was the same – get merrit and raise a faimlie.

Different poems by Burns depict varying attitudes to women. For instance, ‘Willie Wastle’ – which is perhaps an unsuitably-named poem as it’s really about Willie Wastle’s wife – is hardly complimentary towards women. Burns describes her using terms such as ‘dour’, ‘din’, ‘bow-hough’d’ and ‘hem-shin’d’. She allegedly has ‘but ane’ e’e, ‘five rusty teeth, forbye a stump’, ‘a whiskin beard’ and ‘walie nieves like midden-creels’. Burns rounds off every stanza with the line, ‘I wad na gie a button for her’. This Burns is a far cry from the adorer of women the world recognises – he is being extremely disrespectful and takin nae prisoners in mocking her appearance!

This photograph shows the sign for the Willie Wastle Inn in Crosshill, Ayrshire. It depicts Willie’s wife as she is described in the poem.

This photograph shows the sign for the Willie Wastle Inn in Crosshill, Ayrshire. It depicts Willie’s wife as she is described in the poem.

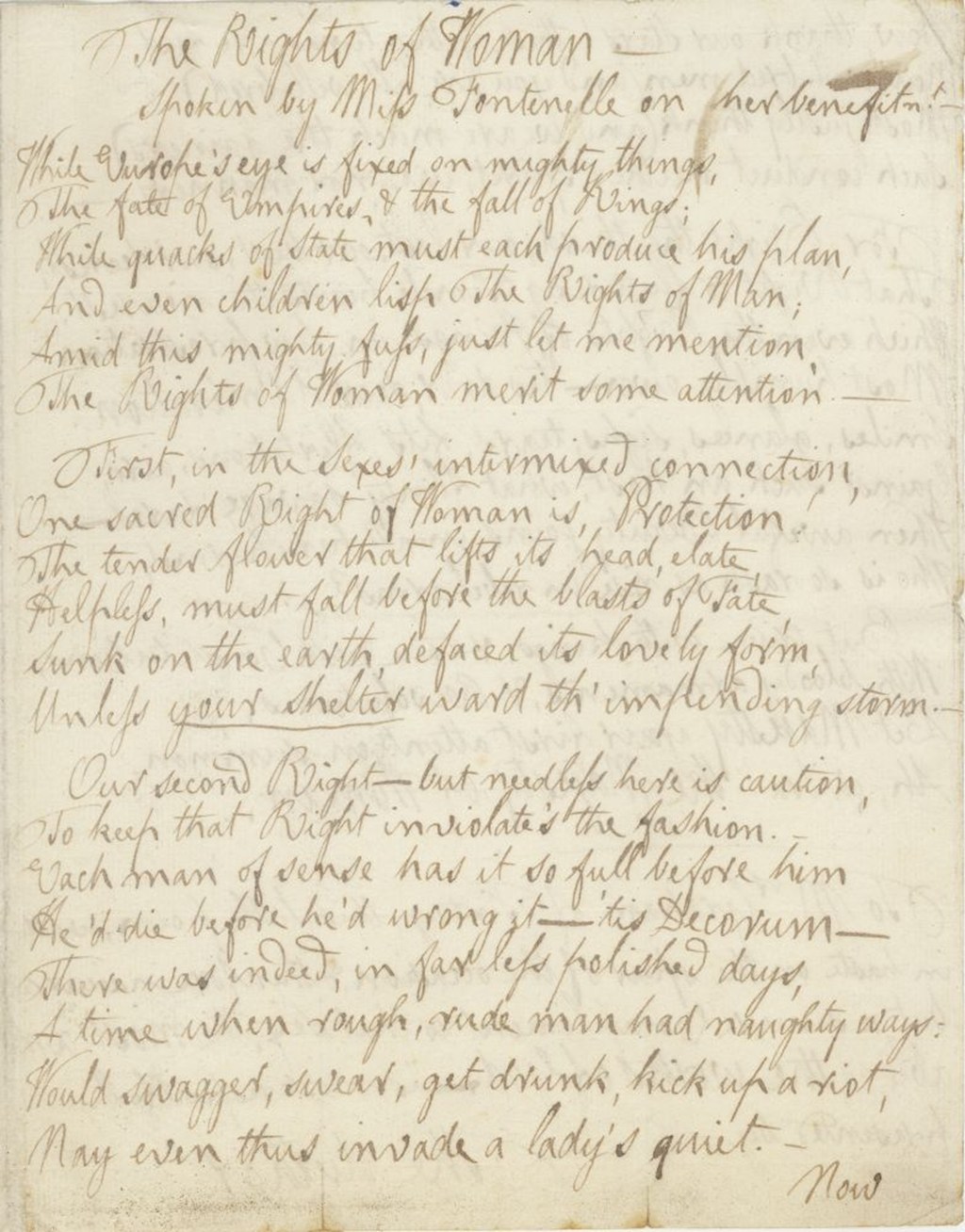

Contrast this with ‘The Rights of Woman’, Burns’s call for folk to remember the rights of women amongst the turbulent atmosphere of the eighteenth century, when ‘even children lisp the Rights of Man’. At first glance this seems like Burns being exceptionally forward-thinking for the 1700s – however, the ‘rights’ in question are: the right to protection, the right to decorum and the right to admiration. So really, Burns’s progressive rally for the rights of women is patronising and objectifying, which is a step up from outright insulting maybe, but still no brilliant.

This is a copy of ‘The Rights of Woman’ written by Burns in 1793 and sent to Mrs Graham of Fintry.

Then we have ‘It’s na, Jean, thy bonie face’ – and thank goodness! This poem is an outpouring of Burns’s love for his wife, Jean Armour – but crucially, it is ‘na her bonie face’ that he admires, ‘altho’ [her] beauty and [her] grace/ Might weel awauk desire’. Instead, it is her mind he loves. This shows Burns’s respect for Jean as a person with her own thoughts and desires. He goes on to say that even if he was not the one to make her happy, that someone would and that she’d be ‘blest’. He even says that he would die for her: this selfless desire to see her happy chimes much more with the image of Burns as the great lover of women that the world knows.

This photograph shows a case containing Jean’s wedding ring, as well as a ring containing a lock of her hair and a ring containing a lock of Burns’s.

Of course, cynics may just read ‘It’s na, Jean…’ as a soppy, hyperbolic gesture to get back in Jean’s good books – ye can make up yer ain mind.

A Fragment of History: Robert Burns’s Glossary Manuscript

The second edition of Robert Burns’s poetry, known as the ‘Edinburgh Edition’ and published in 1787, contained a few differences from his first ‘Kilmarnock’ edition of 1786. For example, the Edinburgh Edition contained 22 more works, as well as a list of subscriber names and a 24-page glossary of Scots words. The collection at the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum contains a fragment of the original manuscript of this glossary:

Written by Burns himself in 1787, each entry has been subsequently scored out; this may have been as each was copied into a new, neater copy which itself has not survived. Words which Burns has glossed include ‘kaittly’, which means ‘to tickle’ or ‘ticklish’, ‘kebbuck’ which means ‘a (usually whole, homemade) cheese’ and ‘kelpies’, ‘mischievous Spirits that haunt fords at night’.

So why was Burns having to define words in his own native language to an audience of people who were also from Scotland?

The inclusion of the glossary is very indicative of the status of Scots language at the end of the 18th century. Since as far back as the Reformation in the mid-16th century, Scots had been subject to a great deal of anglicising influences – for example, English translations of the Bible, the removal of the royal court to London in 1603 and, of course, the Union of the Parliaments between Scotland and England in 1707. All of these influences meant that Scots had undergone a massive change in how it was written and also, we can probably assume, how it was spoken. Some Scottish people even went to elocution-style classes in order to eliminate ‘Scotticisms’ from their speech; Scots was seen as the language of the common people and therefore not fit for the ‘high’ subjects of politics, religion, culture or trade.

Burns was part of a tradition of writers who bucked this trend and started writing in Scots again. However, his Scottish audience were in need of a little assistance when it came to understanding some of the Scots words he used – hence, the glossary. Of course, Burns had fans out-with Scotland as well: before the 18th century was over, editions of his work had been published in Dublin, Belfast, London and New York. Audiences in each of these places would have needed plenty of help to understand Scots language as well.

Burns’s popularisation of Scots took inspiration from writers like Allan Ramsay (father of Allan Ramsay, the painter) and Robert Ferguson (Burns’s ‘elder brother in the muse’). Although the Scots was changed in some ways to make it more intelligible to non-Scots-speaking audiences – for example, inserting apostrophes where English versions of words would have other letters – it did mean speakers of other languages could understand and enjoy Scots literature and language.

The sheer stardom of Burns elevated people’s perception of it further, to the point where people across the globe sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ – a traditional Scottish folk song with words, in Scots – at Hogmanay. Although there is still a long way to go until Scots is back at the same level of recognition it would’ve been at in the early 16th century, campaigns by the Scottish Government and the work of contemporary writers in Scots show its well on its way there. Without Burns, and his predecessors, the Scots language would definitely be in a very different position nowadays.

Halloween

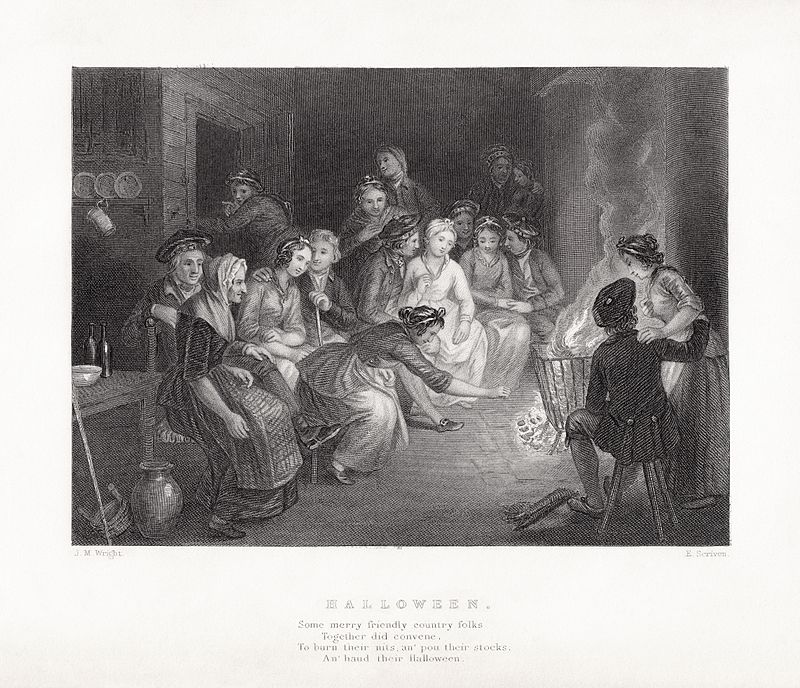

Burns’s poem “Halloween” is a treat to read but a bit of a trick too…

Any reader from the twenty-first century would assume from the title that it is about the now widely celebrated commercial and secular annual event held on the 31st of October. Activities include trick-or-treating – or guising in the Scots language which Burns wrote in and promoted – attending costume parties, carving pumpkins into jack-o’-lanterns (or traditionally turnips in Scotland and Ireland – turnip is tumshie or neep in Scots), dooking for aipples, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories and watching horror films. However, the poem focuses on Scottish folk culture and details courting traditions which were performed on Halloween itself. Interestingly, it is widely believed that many Halloween traditions originated from ancient Celtic harvest festivals – particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain – and that Samhain itself was Christianized as Halloween by the early Church. Thus, there is obviously a deep-rooted connection between Scotland, its people and the celebration of All Hallows Eve.

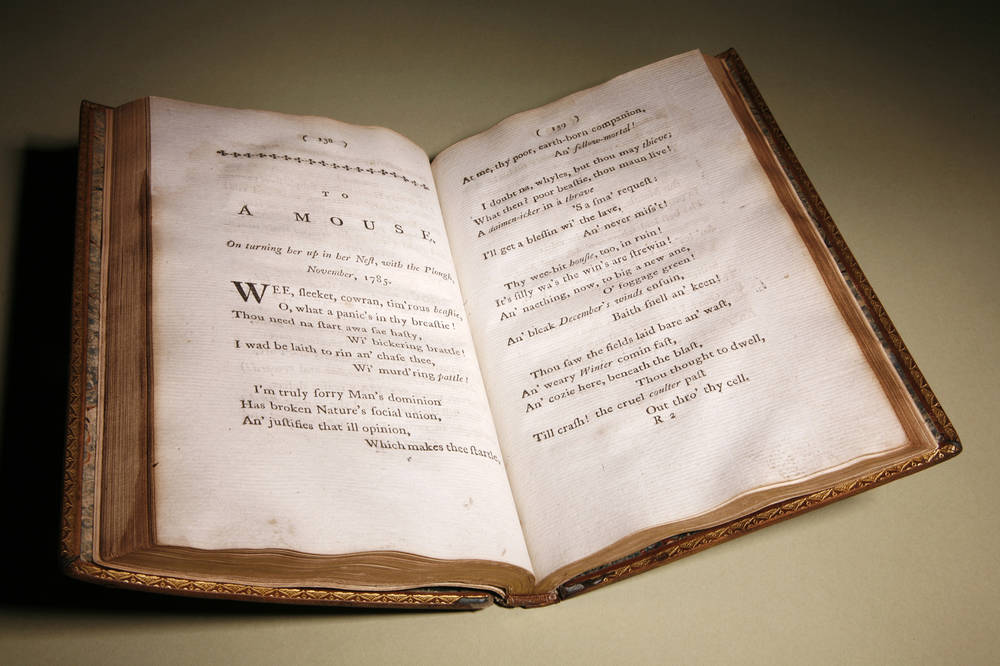

The poem itself was written in 1785 and published in 1786 within Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect – or commonly known as the Kilmarnock Edition – because it was printed and issued by John Wilson of Kilmarnock on 31 July 1786. Although it focuses more on Scottish customs and folklore as opposed to superstition, Burns was interested in the supernatural. His masterful creation of “Tam o’ Shanter” is proof of that as well as his admittance in a letter written in 1787 to Dr. John Moore, a London-based Scottish physician and novelist, as he states:

‘In my infant and boyish days too, I owed much to an old Maid of my Mother’s, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity and superstition. She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the county of tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, inchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery’.

Burns in the first footnote writes that Halloween was thought to be “a night when witches, devils, and other mischief-making beings are abroad on their baneful midnight errands; particularly those aerial people, the fairies, are said on that night to hold a grand anniversary.”

Unlike Burns’s other long narratives such as “Tam o’ Shanter,” “Love and Liberty,” and “The Cotter’s Saturday Night,” “Halloween” has never enjoyed widespread popularity. Critics have argued that is because the poem is one of the densest of Burns’s poems, with a lot of usage of the Scots language, making it harder to read; that its cast of twenty characters often confounds the reader; that the poem’s mysterious folk content alienates readers who do not know anything of the traditions mentioned. Indeed, Burns felt it necessary to provide explanations throughout the poem. Only fourteen of Burns’s works employ his own footnotes. Of the fourteen footnoted works, “Halloween” outnumbers all others with sixteen notes of considerable length. The poem also includes a prose preface, another infrequent device used by Burns in only three other poems. The introduction for the poem states:

The following poem, will, by many readers, be well enough understood; but for the sake of those who are unacquainted with the manners and traditions of the country where the scene is cast, notes are added to give some account of the principal charms and spells of that night, so big with prophecy to the peasantry in the west of Scotland.

Indeed, the footnotes are most illuminating at detailing the intricacies of the rituals and are a crucial part of the poem. Some of my personal favourites are as follows:

[Footnote 5: The first ceremony of Halloween is pulling each a “stock,” or

plant of kail. They must go out, hand in hand, with eyes shut, and pull the

first they meet with: it’s being big or little, straight or crooked, is

prophetic of the size and shape of the grand object of all their spells-the

husband or wife. If any “yird,” or earth, stick to the root, that is “tocher,”

or fortune; and the taste of the “custock,” that is, the heart of the stem, is

indicative of the natural temper and disposition. Lastly, the stems, or, to

give them their ordinary appellation, the “runts,” are placed somewhere above

the head of the door; and the Christian names of the people whom chance brings

into the house are, according to the priority of placing the “runts,” the

names in question.-R. B.]

[Footnote 8: Burning the nuts is a favorite charm. They name the lad and lass to each particular nut, as they lay them in the fire; and according as they burn quietly together, or start from beside one another, the course and issue of the courtship will be.-R.B.]

[Footnote 10: Take a candle and go alone to a looking-glass; eat an apple

before it, and some traditions say you should comb your hair all the time; the

face of your conjungal companion, to be, will be seen in the glass, as if

peeping over your shoulder.-R.B.]

[Footnote 15: Take three dishes, put clean water in one, foul water in another, and leave the third empty; blindfold a person and lead him to the hearth where the dishes are ranged; he (or she) dips the left hand; if by chance in the clean water, the future (husband or) wife will come to the bar of matrimony a maid; if in the foul, a widow; if in the empty dish, it foretells, with equal certainty, no marriage at all. It is repeated three

times, and every time the arrangement of the dishes is altered.-R.B.]

Arguably, the poem has been appreciated more as a kind of historical testimony rather than artistic work. However, it is still a fascinating piece of poetry and definitely should be celebrated for its documentation and preservation of divination traditions and folklore customs which were performed on now one of the most widely celebrated festive days in Western calendars.

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)

Read the full poem here: http://www.robertburns.org/works/74.shtml

Burns on Beasties

On the BBC’s website it is listed that there are 118 poems written by our beloved bard Robert Burns with the theme of nature, however, I would argue that there is so many more as nature – a subject which was very close to his heart – is inextricably intertwined in a number of his works.

The reason nature is a genre featured so heavily within Burns’s works can be traced back to his upbringing and lifestyle. Being born in the but-and-ben Burns Cottage in Alloway, he was introduced to the ways of farmlife from childhood. He worked with his family closely there and at multiple farms thereafter such as Mount Oliphant and Lochlea Farm. Burns and his brother Gilbert even farmed at Mossgiel Farm when his father died. He did not just have connections with the land in his younger years but as an adult as well as he worked as a farmer alongside his career as a poet and songwriter. His last farming endevaour was at Ellisland Farm in Dumfrieshire. His rural upbringing and argicultural employment earned him his nickname as “The Ploughman Poet” by the artistocratic society of Edinburgh. Burns lived in Edinburgh for only two years – the city which he described as “noise and nonsense” – to return to his rural roots.

Firstly, I would ask: what is nature? It is defined as the phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals and the landscape. Burns did not neglect any of these three aspects and used them frequently as the inspiration of his works. He did various works which refer to plants such as To a Mountain Daisy, My Luve is Like a Red Red Rose and The Rosebud. Some of my personal favourite works of Burns which talk about other environmental features include Sweet Afton (about a river) and My Heart’s in the Highlands (which of course is about one of the most rugged, scenic and breath-taking landscapes in the world).

However, what this blog will mainly focus on is that Burns was most notably an animal lover. This is conveyed in his works On Glenriddell’s Fox Breaking his Chain, The Wounded Hare, Address to a Woodlark, The Twa Dogs, To a Louse and the renowned and much adored To a Mouse. This last poem – which was written in 1786 and published in the Kilmarnock Edition – is a perfect example of Burns’s humanity as this poem reflects his concern for animal welfare, his consciousness of humankind’s effect on nature and has empathy for a small creature which is widely considered as “vermin”. This was very ahead of his time and is a concern that is currently proving to be a huge issue as more and more animals become extinct because of human’s destructive actions in the twenty-first century.

The Twa Dogs poem, written in 1796, is another great work of Burns’s which gives the two dogs human-like intellect and the ability to express themselves as it has an upper-class pedigree, Caesar, and an ordinary working collie, Luath, who chat about the differing lives of the social classes. The name “Luath” comes from Ossian’s epic poem Fingal. The Twa Dogs immortalizes Burns’s own dog Luath who came to a cruel end. On the morning of 13th February 1784 Robert and his sister Isabella were distressed to find the poisoned body of Robert’s dog Luath outside their door – the act of a vengeful neighbour. Arguably, Burns intended this poem as a memorial to his canine friend.

An example of one of Burn’s lesser-known poems is The Wounded Hare which was written in 1789. Below are the first three stanzas out of five that complete this poem:

Inhuman man! curse on thy barb’rous art,

And blasted be thy murder-aiming eye;

May never pity soothe thee with a sigh,

Nor ever pleasure glad thy cruel heart!

Go live, poor wand’rer of the wood and field!

The bitter little that of life remains:

No more the thickening brakes and verdant plains

To thee a home, or food, or pastime yield.

Seek, mangled wretch, some place of wonted rest,

No more of rest, but now thy dying bed!

The sheltering rushes whistling o’er thy head,

The cold earth with thy bloody bosom prest.

The word choice makes the moral message of this poem is clear: Burns is vehemently opposed to shooting. The passion and intensity of Burns’s thoughts on this is quite surprising as one would think that as a farmer he would be used to or even dependent on killing animals, however, meat consumption was not as prominent in the eighteenth century as farm animals were only killed for food in old age or special occasions. The family’s provision of milk, cheese, butter and wool came directly from their own animals, and the health and wellbeing of these creatures were paramount. Furthermore they would share the same roof over their heads with them, thus creating strong bonds with their farm animals, and apparently Burns lost his temper with a farm-worked once when the man did not cut the potatoes small enough and Burns was frantic that the beasts might choke on them.

Below is the third stanza of the powerful poem On Glenriddell’s Fox Breaking His Chain written in 1791:

Glenriddell! Whig without a stain,

A Whig in principle and grain,

Could’st thou enslave a free-born creature,

A native denizen of Nature?

How could’st thou, with a heart so good,

(A better ne’er was sluiced with blood!)

Nail a poor devil to a tree,

That ne’er did harm to thine or thee?

Again, you can clearly see that Burns is opposed to the cruel treatment of a “free-born creature” and is in disbelief of the actions of the good-hearted Glenriddell’s actions.

However, one could argue that nature was so deeply rooted in Burns’s psyche – and he quite literally was surrounded by it living on a farm – that he could not escape from being inspired to write about it. An example of this is in his masterpiece Tam o’ Shanter. It is an epic narrative poem written in 1790 which features folklore, superstition, witchcraft and gothic themes… but it also has one of his most poignant and beautiful quotes in which Burns really philosophically details the nature of nature:

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white–then melts for ever;

Or like the borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.–

Nae man can tether time or tide;

The hour approaches Tam maun ride;

Burns is saying that nature’s beauty is wistful, forever-changing and is out of the control of humankind as he insightfully states “nae man can tether time or tide”.

In terms of this poem, another point is worth mentioning: the hero of this tale is a horse. Again Burns’s admiration and respect for animals is encompassed in the heroism of Meg, Tam’s horse, who against all odds does get him home in one piece although the same cannot be said for her. Burns was a brilliant horse-rider and would have relied heavily on his four-legged companion as a mode of transportation to socialise, to plough fields and to work as an excise man.

All in all Burns would have been regarded nowadays as an advocate for animal welfare and his works which have animals or nature at their core reflect his love for nature and are some of his most passionate, most thought-provoking and most heart-rending.

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)