literature

Four Women Who Inspired Burns

In honour of Women’s History Month, throughout March the RBBM Facebook and Twitter have shared poems linked to influential women in Robert Burns’s life. We thought we’d round off the month with a blog exploring each of these ladies in more detail!

First up is Jean Armour, Robert’s wife. She was born 25th February 1765 in Mauchline, Ayrshire. Whilst growing up, Jean was renowned for her beauty and was part of a group of young women often referred to as ‘the Belles of Mauchline’. She met Robert when she was around eighteen, and less than two years later she was pregnant with his child – her father famously fainted when told that Robert was the father! He refused to allow the couple to marry – this meant he would rather Jean be a single mother than married to Robert, which speaks volumes about Robert’s reputation!

Despite this less than promising start to their relationship, Jean and Robert were formally married on 5th August 1788 – Jean’s father had come round to the idea after Robert’s poetry success. They had a mostly happy marriage, despite Robert’s famous infidelities – Jean herself said that he should have had ‘twa wives’.

Jean and her family moved to Dumfries in 1791 and this is where Robert died in 1796. Jean could not attend his funeral as she was in labour with their ninth child, Maxwell. Tragically, Maxwell died at the age of two – just four of the couple’s children survived to adulthood. However, Jean did also look after Betty Park (Robert’s child to Ann Park) and they had a good relationship. After Robert’s death, Jean never remarried, and she lived in the house they had shared in Dumfries until she died 26th March 1834 – she outlived her husband by thirty-eight years.

Next is Agnes Burnes, née Broun – the Bard’s mother. Agnes was born 17th March 1732 near Kirkoswald in Ayrshire. Her mother died when she was just ten years old; being the eldest sibling, it was then Agnes’s responsibility to care for the family until her father remarried two years later. However, Agnes and her new step-mother did not get on well, and Agnes was sent to live with her maternal grandmother in Maybole. She instilled in Agnes a great love for Scottish folk song and music.

Agnes met William Burnes (spelled differently but pronounced the same as ‘Burns’) in 1756 and they married on 3rd December 1757. They settled in the clay biggin William had built in Alloway; Robert Burns was the eldest of their seven children. It is thought that Agnes was a great influence on Robert’s own love of Scottish folk song and music, just as her grandmother had been to her. After William died in 1784, Agnes went to live with her son Gilbert. She moved around with his family until her death, at the age of eighty-seven, on 14th January 1820.

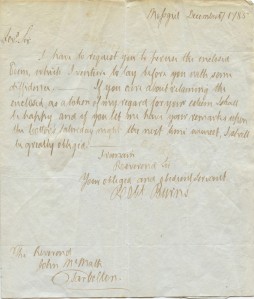

The third woman we featured this month is Frances Dunlop, a wealthy heiress almost thirty years older than Burns. Born 16th April 1730, her maiden name was Wallace, and her family claimed descent from William Wallace himself! Frances married at eighteen, when her husband, John Dunlop, was in his forties. They had a happy life together – however, John died in 1785. In the same year, Frances’s childhood home and lands were lost to the family. These incidents caused her humongous grief and she fell into a prolonged depression.

What finally roused her was Robert Burns’s poem ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’. She enjoyed reading it so much that she contacted Robert to ask for more copies and to invite him to her home – this began a long and friendly correspondence that lasted until the end of Robert’s life. Frances treated him almost like another son, praising his achievements and admonishing his indiscretions. She even offered advice on drafts of poetry and songs he would send her, the most famous of these being ‘Auld Lang Syne’! Although there was a two-year gap in their correspondence after Burns had offended Frances with some comments she deemed radical, Frances sent him a reconciliatory letter mere days before Robert’s death. She outlived him by nearly twenty years, dying 24th May 1815.

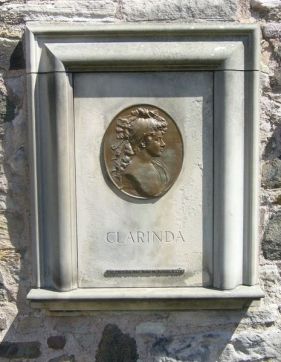

The last woman featured is Agnes Maclehose, aka the ‘Clarinda’ to Burns’s ‘Sylvander’. Agnes was born 26th April 1758 in Glasgow. She grew up to be a very articulate, well-educated and beautiful woman. She married at eighteen, but the marriage was an unhappy one and she separated from her husband in 1780.

Agnes met Robert Burns several years later at a party in Edinburgh – they were immediately taken with each other, and she wrote to him to invite him to tea at her home. Although an accident prevented this from happening, there began a long series of love letters and love poetry sent between the two. They used the pseudonyms ‘Clarinda’ and ‘Sylvander’. Despite the intensity of their correspondence, it is widely-thought that their affair was unconsummated. As Agnes was an incredibly pious woman and, although separated, still married, this makes sense.

In 1791 Agnes sailed for Jamaica to attempt to reconcile with her husband – however, he had started a family with another woman, so she returned to Scotland after only a few months. She met Robert for the last time in December of that year. For the rest of her life Agnes took great care of her letters from Robert, and after his death she even negotiated to have the letters she had sent to him returned to her.

In 1821 Agnes had tea with Jean Armour in Edinburgh. The two women, who could have been viewed as rivals of sorts, got on well and talked at length about their families, as well as their shared regard for Robert Burns. Agnes died twenty years later, at the age of eighty-three, on 23rd October 1841.

You can find the original Facebook and Twitter posts at https://www.facebook.com/RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum/ and https://twitter.com/RobertBurnsNTS.

Burns and his Wumin: The Attitudes to Women Found in Burns’s Poetry

As it’s Women’s History Month, one of the Learning Trainees here at RBBM, Caitlin Walker, has written about the attitudes to women found in Burns’s poetry. She has written the post in a similar way to how she would speak it, which is why there is a mixture of Scots and English language.

Maist folk know that Robert Burns enjoyed the company of women – his famous love affairs, the hundreds of poems and songs they inspired and the thirteen (that we know of!) weans he fathered attest to that. But what did he actually think of women?

Burns was born and lived his life during the latter half of the eighteenth century, a time when women couldnae vote and were rarely, if ever, formally educatit. Gender roles were strictly prescribed – for instance, women of the working class were given no formal education but taught how to run a hoose and look after a faimlie. Tasks were divided by gender completely, to the extent that women milked the coos but men mucked oot the byre, and during harvest time men used the scythe while women used the heuk. Women of higher classes would have learned literacy and maybe even another language or a musical instrument, but the expectation was the same – get merrit and raise a faimlie.

Different poems by Burns depict varying attitudes to women. For instance, ‘Willie Wastle’ – which is perhaps an unsuitably-named poem as it’s really about Willie Wastle’s wife – is hardly complimentary towards women. Burns describes her using terms such as ‘dour’, ‘din’, ‘bow-hough’d’ and ‘hem-shin’d’. She allegedly has ‘but ane’ e’e, ‘five rusty teeth, forbye a stump’, ‘a whiskin beard’ and ‘walie nieves like midden-creels’. Burns rounds off every stanza with the line, ‘I wad na gie a button for her’. This Burns is a far cry from the adorer of women the world recognises – he is being extremely disrespectful and takin nae prisoners in mocking her appearance!

This photograph shows the sign for the Willie Wastle Inn in Crosshill, Ayrshire. It depicts Willie’s wife as she is described in the poem.

This photograph shows the sign for the Willie Wastle Inn in Crosshill, Ayrshire. It depicts Willie’s wife as she is described in the poem.

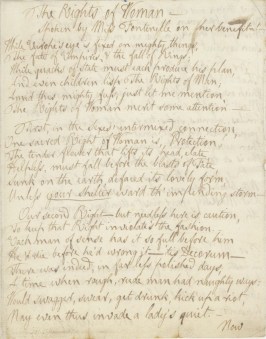

Contrast this with ‘The Rights of Woman’, Burns’s call for folk to remember the rights of women amongst the turbulent atmosphere of the eighteenth century, when ‘even children lisp the Rights of Man’. At first glance this seems like Burns being exceptionally forward-thinking for the 1700s – however, the ‘rights’ in question are: the right to protection, the right to decorum and the right to admiration. So really, Burns’s progressive rally for the rights of women is patronising and objectifying, which is a step up from outright insulting maybe, but still no brilliant.

This is a copy of ‘The Rights of Woman’ written by Burns in 1793 and sent to Mrs Graham of Fintry.

Then we have ‘It’s na, Jean, thy bonie face’ – and thank goodness! This poem is an outpouring of Burns’s love for his wife, Jean Armour – but crucially, it is ‘na her bonie face’ that he admires, ‘altho’ [her] beauty and [her] grace/ Might weel awauk desire’. Instead, it is her mind he loves. This shows Burns’s respect for Jean as a person with her own thoughts and desires. He goes on to say that even if he was not the one to make her happy, that someone would and that she’d be ‘blest’. He even says that he would die for her: this selfless desire to see her happy chimes much more with the image of Burns as the great lover of women that the world knows.

This photograph shows a case containing Jean’s wedding ring, as well as a ring containing a lock of her hair and a ring containing a lock of Burns’s.

Of course, cynics may just read ‘It’s na, Jean…’ as a soppy, hyperbolic gesture to get back in Jean’s good books – ye can make up yer ain mind.

A Fragment of History: Robert Burns’s Glossary Manuscript

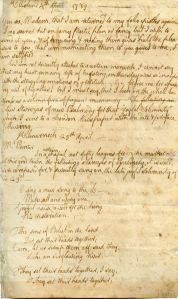

The second edition of Robert Burns’s poetry, known as the ‘Edinburgh Edition’ and published in 1787, contained a few differences from his first ‘Kilmarnock’ edition of 1786. For example, the Edinburgh Edition contained 22 more works, as well as a list of subscriber names and a 24-page glossary of Scots words. The collection at the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum contains a fragment of the original manuscript of this glossary:

Written by Burns himself in 1787, each entry has been subsequently scored out; this may have been as each was copied into a new, neater copy which itself has not survived. Words which Burns has glossed include ‘kaittly’, which means ‘to tickle’ or ‘ticklish’, ‘kebbuck’ which means ‘a (usually whole, homemade) cheese’ and ‘kelpies’, ‘mischievous Spirits that haunt fords at night’.

So why was Burns having to define words in his own native language to an audience of people who were also from Scotland?

The inclusion of the glossary is very indicative of the status of Scots language at the end of the 18th century. Since as far back as the Reformation in the mid-16th century, Scots had been subject to a great deal of anglicising influences – for example, English translations of the Bible, the removal of the royal court to London in 1603 and, of course, the Union of the Parliaments between Scotland and England in 1707. All of these influences meant that Scots had undergone a massive change in how it was written and also, we can probably assume, how it was spoken. Some Scottish people even went to elocution-style classes in order to eliminate ‘Scotticisms’ from their speech; Scots was seen as the language of the common people and therefore not fit for the ‘high’ subjects of politics, religion, culture or trade.

Burns was part of a tradition of writers who bucked this trend and started writing in Scots again. However, his Scottish audience were in need of a little assistance when it came to understanding some of the Scots words he used – hence, the glossary. Of course, Burns had fans out-with Scotland as well: before the 18th century was over, editions of his work had been published in Dublin, Belfast, London and New York. Audiences in each of these places would have needed plenty of help to understand Scots language as well.

Burns’s popularisation of Scots took inspiration from writers like Allan Ramsay (father of Allan Ramsay, the painter) and Robert Ferguson (Burns’s ‘elder brother in the muse’). Although the Scots was changed in some ways to make it more intelligible to non-Scots-speaking audiences – for example, inserting apostrophes where English versions of words would have other letters – it did mean speakers of other languages could understand and enjoy Scots literature and language.

The sheer stardom of Burns elevated people’s perception of it further, to the point where people across the globe sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ – a traditional Scottish folk song with words, in Scots – at Hogmanay. Although there is still a long way to go until Scots is back at the same level of recognition it would’ve been at in the early 16th century, campaigns by the Scottish Government and the work of contemporary writers in Scots show its well on its way there. Without Burns, and his predecessors, the Scots language would definitely be in a very different position nowadays.

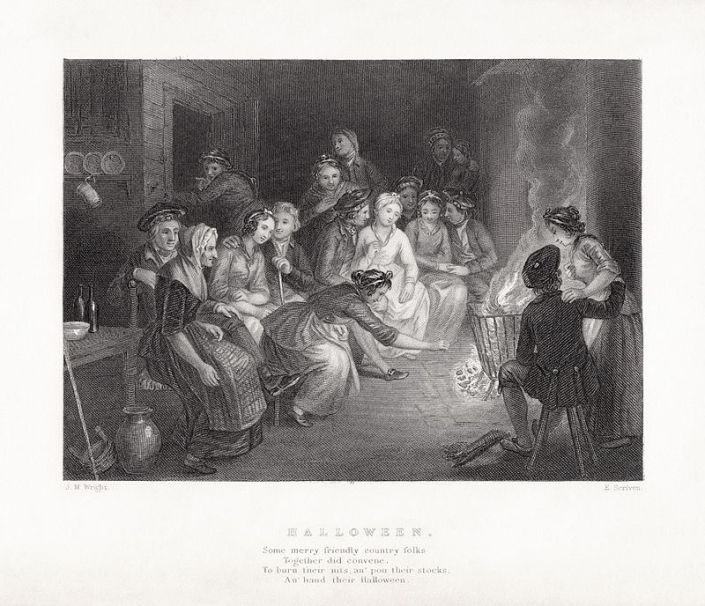

Halloween

Burns’s poem “Halloween” is a treat to read but a bit of a trick too…

Any reader from the twenty-first century would assume from the title that it is about the now widely celebrated commercial and secular annual event held on the 31st of October. Activities include trick-or-treating – or guising in the Scots language which Burns wrote in and promoted – attending costume parties, carving pumpkins into jack-o’-lanterns (or traditionally turnips in Scotland and Ireland – turnip is tumshie or neep in Scots), dooking for aipples, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories and watching horror films. However, the poem focuses on Scottish folk culture and details courting traditions which were performed on Halloween itself. Interestingly, it is widely believed that many Halloween traditions originated from ancient Celtic harvest festivals – particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain – and that Samhain itself was Christianized as Halloween by the early Church. Thus, there is obviously a deep-rooted connection between Scotland, its people and the celebration of All Hallows Eve.

The poem itself was written in 1785 and published in 1786 within Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect – or commonly known as the Kilmarnock Edition – because it was printed and issued by John Wilson of Kilmarnock on 31 July 1786. Although it focuses more on Scottish customs and folklore as opposed to superstition, Burns was interested in the supernatural. His masterful creation of “Tam o’ Shanter” is proof of that as well as his admittance in a letter written in 1787 to Dr. John Moore, a London-based Scottish physician and novelist, as he states:

‘In my infant and boyish days too, I owed much to an old Maid of my Mother’s, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity and superstition. She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the county of tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, inchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery’.

Burns in the first footnote writes that Halloween was thought to be “a night when witches, devils, and other mischief-making beings are abroad on their baneful midnight errands; particularly those aerial people, the fairies, are said on that night to hold a grand anniversary.”

Unlike Burns’s other long narratives such as “Tam o’ Shanter,” “Love and Liberty,” and “The Cotter’s Saturday Night,” “Halloween” has never enjoyed widespread popularity. Critics have argued that is because the poem is one of the densest of Burns’s poems, with a lot of usage of the Scots language, making it harder to read; that its cast of twenty characters often confounds the reader; that the poem’s mysterious folk content alienates readers who do not know anything of the traditions mentioned. Indeed, Burns felt it necessary to provide explanations throughout the poem. Only fourteen of Burns’s works employ his own footnotes. Of the fourteen footnoted works, “Halloween” outnumbers all others with sixteen notes of considerable length. The poem also includes a prose preface, another infrequent device used by Burns in only three other poems. The introduction for the poem states:

The following poem, will, by many readers, be well enough understood; but for the sake of those who are unacquainted with the manners and traditions of the country where the scene is cast, notes are added to give some account of the principal charms and spells of that night, so big with prophecy to the peasantry in the west of Scotland.

Indeed, the footnotes are most illuminating at detailing the intricacies of the rituals and are a crucial part of the poem. Some of my personal favourites are as follows:

[Footnote 5: The first ceremony of Halloween is pulling each a “stock,” or

plant of kail. They must go out, hand in hand, with eyes shut, and pull the

first they meet with: it’s being big or little, straight or crooked, is

prophetic of the size and shape of the grand object of all their spells-the

husband or wife. If any “yird,” or earth, stick to the root, that is “tocher,”

or fortune; and the taste of the “custock,” that is, the heart of the stem, is

indicative of the natural temper and disposition. Lastly, the stems, or, to

give them their ordinary appellation, the “runts,” are placed somewhere above

the head of the door; and the Christian names of the people whom chance brings

into the house are, according to the priority of placing the “runts,” the

names in question.-R. B.]

[Footnote 8: Burning the nuts is a favorite charm. They name the lad and lass to each particular nut, as they lay them in the fire; and according as they burn quietly together, or start from beside one another, the course and issue of the courtship will be.-R.B.]

[Footnote 10: Take a candle and go alone to a looking-glass; eat an apple

before it, and some traditions say you should comb your hair all the time; the

face of your conjungal companion, to be, will be seen in the glass, as if

peeping over your shoulder.-R.B.]

[Footnote 15: Take three dishes, put clean water in one, foul water in another, and leave the third empty; blindfold a person and lead him to the hearth where the dishes are ranged; he (or she) dips the left hand; if by chance in the clean water, the future (husband or) wife will come to the bar of matrimony a maid; if in the foul, a widow; if in the empty dish, it foretells, with equal certainty, no marriage at all. It is repeated three

times, and every time the arrangement of the dishes is altered.-R.B.]

Arguably, the poem has been appreciated more as a kind of historical testimony rather than artistic work. However, it is still a fascinating piece of poetry and definitely should be celebrated for its documentation and preservation of divination traditions and folklore customs which were performed on now one of the most widely celebrated festive days in Western calendars.

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)

Read the full poem here: http://www.robertburns.org/works/74.shtml

Burns on Beasties

On the BBC’s website it is listed that there are 118 poems written by our beloved bard Robert Burns with the theme of nature, however, I would argue that there is so many more as nature – a subject which was very close to his heart – is inextricably intertwined in a number of his works.

The reason nature is a genre featured so heavily within Burns’s works can be traced back to his upbringing and lifestyle. Being born in the but-and-ben Burns Cottage in Alloway, he was introduced to the ways of farmlife from childhood. He worked with his family closely there and at multiple farms thereafter such as Mount Oliphant and Lochlea Farm. Burns and his brother Gilbert even farmed at Mossgiel Farm when his father died. He did not just have connections with the land in his younger years but as an adult as well as he worked as a farmer alongside his career as a poet and songwriter. His last farming endevaour was at Ellisland Farm in Dumfrieshire. His rural upbringing and argicultural employment earned him his nickname as “The Ploughman Poet” by the artistocratic society of Edinburgh. Burns lived in Edinburgh for only two years – the city which he described as “noise and nonsense” – to return to his rural roots.

Firstly, I would ask: what is nature? It is defined as the phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals and the landscape. Burns did not neglect any of these three aspects and used them frequently as the inspiration of his works. He did various works which refer to plants such as To a Mountain Daisy, My Luve is Like a Red Red Rose and The Rosebud. Some of my personal favourite works of Burns which talk about other environmental features include Sweet Afton (about a river) and My Heart’s in the Highlands (which of course is about one of the most rugged, scenic and breath-taking landscapes in the world).

However, what this blog will mainly focus on is that Burns was most notably an animal lover. This is conveyed in his works On Glenriddell’s Fox Breaking his Chain, The Wounded Hare, Address to a Woodlark, The Twa Dogs, To a Louse and the renowned and much adored To a Mouse. This last poem – which was written in 1786 and published in the Kilmarnock Edition – is a perfect example of Burns’s humanity as this poem reflects his concern for animal welfare, his consciousness of humankind’s effect on nature and has empathy for a small creature which is widely considered as “vermin”. This was very ahead of his time and is a concern that is currently proving to be a huge issue as more and more animals become extinct because of human’s destructive actions in the twenty-first century.

The Twa Dogs poem, written in 1796, is another great work of Burns’s which gives the two dogs human-like intellect and the ability to express themselves as it has an upper-class pedigree, Caesar, and an ordinary working collie, Luath, who chat about the differing lives of the social classes. The name “Luath” comes from Ossian’s epic poem Fingal. The Twa Dogs immortalizes Burns’s own dog Luath who came to a cruel end. On the morning of 13th February 1784 Robert and his sister Isabella were distressed to find the poisoned body of Robert’s dog Luath outside their door – the act of a vengeful neighbour. Arguably, Burns intended this poem as a memorial to his canine friend.

An example of one of Burn’s lesser-known poems is The Wounded Hare which was written in 1789. Below are the first three stanzas out of five that complete this poem:

Inhuman man! curse on thy barb’rous art,

And blasted be thy murder-aiming eye;

May never pity soothe thee with a sigh,

Nor ever pleasure glad thy cruel heart!

Go live, poor wand’rer of the wood and field!

The bitter little that of life remains:

No more the thickening brakes and verdant plains

To thee a home, or food, or pastime yield.

Seek, mangled wretch, some place of wonted rest,

No more of rest, but now thy dying bed!

The sheltering rushes whistling o’er thy head,

The cold earth with thy bloody bosom prest.

The word choice makes the moral message of this poem is clear: Burns is vehemently opposed to shooting. The passion and intensity of Burns’s thoughts on this is quite surprising as one would think that as a farmer he would be used to or even dependent on killing animals, however, meat consumption was not as prominent in the eighteenth century as farm animals were only killed for food in old age or special occasions. The family’s provision of milk, cheese, butter and wool came directly from their own animals, and the health and wellbeing of these creatures were paramount. Furthermore they would share the same roof over their heads with them, thus creating strong bonds with their farm animals, and apparently Burns lost his temper with a farm-worked once when the man did not cut the potatoes small enough and Burns was frantic that the beasts might choke on them.

Below is the third stanza of the powerful poem On Glenriddell’s Fox Breaking His Chain written in 1791:

Glenriddell! Whig without a stain,

A Whig in principle and grain,

Could’st thou enslave a free-born creature,

A native denizen of Nature?

How could’st thou, with a heart so good,

(A better ne’er was sluiced with blood!)

Nail a poor devil to a tree,

That ne’er did harm to thine or thee?

Again, you can clearly see that Burns is opposed to the cruel treatment of a “free-born creature” and is in disbelief of the actions of the good-hearted Glenriddell’s actions.

However, one could argue that nature was so deeply rooted in Burns’s psyche – and he quite literally was surrounded by it living on a farm – that he could not escape from being inspired to write about it. An example of this is in his masterpiece Tam o’ Shanter. It is an epic narrative poem written in 1790 which features folklore, superstition, witchcraft and gothic themes… but it also has one of his most poignant and beautiful quotes in which Burns really philosophically details the nature of nature:

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white–then melts for ever;

Or like the borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.–

Nae man can tether time or tide;

The hour approaches Tam maun ride;

Burns is saying that nature’s beauty is wistful, forever-changing and is out of the control of humankind as he insightfully states “nae man can tether time or tide”.

In terms of this poem, another point is worth mentioning: the hero of this tale is a horse. Again Burns’s admiration and respect for animals is encompassed in the heroism of Meg, Tam’s horse, who against all odds does get him home in one piece although the same cannot be said for her. Burns was a brilliant horse-rider and would have relied heavily on his four-legged companion as a mode of transportation to socialise, to plough fields and to work as an excise man.

All in all Burns would have been regarded nowadays as an advocate for animal welfare and his works which have animals or nature at their core reflect his love for nature and are some of his most passionate, most thought-provoking and most heart-rending.

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)

‘The descendant of the immortal Wallace’

Throughout his life, Robert Burns was inspired by women. He grew up listening to the Scottish songs and folklore of his mother, Agnes, and distant cousin, Betty Davidson; fell in love time and again with a new bonnie lassie; and fathered several much loved daughters of his own who inspired his affections and poetry. Few relationships however are as well documented or as important to his works as his friendship with Mrs Frances Anna Wallace Dunlop, whose support and patronage were invaluable to the Bard for the majority of his publishing life.

Born in 1730, Frances Anna Wallace was the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas Wallace of Craigie and Dame Eleanora Agnew. Sir Thomas claimed to have been a descendant of Sir Richard, cousin of William Wallace – a connection which Burns was later delighted by. At the age of 17, Frances married John Dunlop of Dunlop and the couple went on to have 7 sons and 6 daughters. Their happiness was not to last however, as John died in 1785 resulting in Frances falling into a ‘long and severe illness, which reduced her mind to the most distressing state of depression’. This would have been an affliction Burns was also all too used to.

It was as she was recovering from this illness that a friend gave her a copy of The Cotter’s Saturday Night to read. So delighted was she with it that she sent, according to Gilbert Burns, ‘a very obliging letter to my brother, desiring him to send her half a dozen copies of his Poems, if he had them to spare, and begging he would do her the pleasure of calling at Dunlop House as soon as convenient’. The Bard responded by sending her 5 copies of his Kilmarnock Edition and a promise to call on her on return from his trip to Edinburgh. It was the start of a very important friendship.

Burns visited Mrs Dunlop at least five times throughout his life, and wrote more often to her than any other correspondent, sending her copies of his poems and drafts of letters intended for others. She in return wrote to him of her family troubles, as well as counselling him on career choices and urging him to modify what she described as his ‘undecency’ in relation to his affairs with women. She described his correspondence as ‘an acquisition for which mine can make no return, as a commerce in which I alone am the gainer; the sight of your hand gives me inexpressible pleasure…’ It would appear, in saying this, that she underestimated the value Burns placed on her friendship, as his increasingly desperate attempts to illicit a response from her after their falling out demonstrate.

This falling out occurred in 1794. With two of her daughters marrying French refugees and various members of her family having army connections, Mrs Dunlop had hinted at her disapproval of Burns’s apparent sympathies with revolutionaries in France in previous correspondence. He failed to take the hint and wrote in a letter of December 1794, referring to King Louis and Marie Antoinette, ‘What is there in the delivering over a purged Blockhead & an unprincipled Prostitute to the hands of the hangman, that it should arrest for a moment, attention in an eventful hour…?’ This offence was a step too far.

Burns sent Mrs Dunlop two further letters without reply, apparently completely oblivious to what could have caused her anger. ‘What sin of ignorance I have committed against so highly a valued friend I am utterly at a loss to guess’ he wrote in January 1796, ‘…Will you be so obliging, dear Madam, as to condescend on that my offence which you seem determined to punish with a deprivation of that friendship which once was the source of my highest enjoyments?’ On receiving no response, his final letter to her was sent just days before his death informing her that his illness would ‘speedily send me beyond that bourne whence no traveller returns’ and bestowing praise upon her friendship. It is believed that she did relent on receiving this, and one of the last things Burns was able to read was a message of reconciliation from her.

Mrs Dunlop survived the poet by another 19 years, dying in 1815. Her friendship and patronage were hugely valued by Burns, and her impact on the poet’s life and works should be regarded as just as important as that of other key women in his life. She is buried in Dumfries, Scotland but her words and thoughts live on in her letters to Scotland’s National Bard.

Forging the Bard

From the moment of Burns’s death in 1796, a hunger to obtain original versions of his works, letters and personal items began. Naturally, this led to a number of unscrupulous individuals creating forgeries, or passing off unconnected objects as having belonged to the Bard. Few were as prolific or notorious however as one Alexander Howland Smith, known as ‘Antique Smith’, a Scottish document forger of the late C19th whose efforts are now collection items in their own right.

Born in 1859, Smith was forging documents in Edinburgh by the 1880s, and began selling his forgeries in 1886. He frequented second hand bookshops, purchasing volumes of old books with blank fly leaves, which he then insisted upon carrying home himself rather than asking for them to be delivered – despite their weight (a practise many bookshop owners found strange!). From these blank fly leaves, Smith forged poems, autographs and historical letters purportedly written by a number of historical figures including Mary Queen of Scots, Walter Scott and Burns himself. He gave his documents an antique appearance by dipping them in weak tea!

Things started to go wrong for Smith when manuscript collector James MacKenzie put some of the letters in his ‘Rillbank Collection’ up for auction in 1891, and the auctioneer himself cast doubt on their authenticity by refusing to verify their provenance. A little while later MacKenzie published a letter, supposedly written by Burns, in the Cumnock Express. After a bit of research, one reader discovered that the recipient of this supposed letter, John Hill, had never actually existed, throwing doubt on the entire Rillbank Collection. MacKenzie later published two ‘Burns’ poems in the same paper, only to discover that one of them had been written when Burns was only 7 by an entirely different poet! Other forgeries were discovered in the collection of an American, who had purchased letters from Edinburgh manuscript collector James Stillie.

By now, word was spreading about the forgeries. In 1892, The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch published an article on the issue, and a reader recognised the handwriting on the facsimiles included as that of Smith, at that time working as chief clerk for a lawyer, Thomas Henry Ferrie. Smith was duly arrested and his trial began on June 26th 1893.

Smith was charged with selling forgeries under false pretences. He was found guilty, but the jury recommended leniency and he was sentenced to 12 months. Experts later said that some of his forgeries were not of particularly high quality – often they were dated after the death of their supposed writer, or created using modern paper or writing tools. It is more than possible that many of those who sold his forgeries on would have been fully aware that they were not genuine. It is unknown exactly how many of ‘Antique’ Smith’s forgeries are still around, but we do know that we have some of them in our collection!

Burns’s Commonplace Books

Commonplace Books first became significant in early modern Europe as a way of compiling knowledge. ‘Commonplace’ is a translation of the Latin phrase locus communis which means ‘a theme or argument of general application’. This original definition has been expanded to now mean a collection of materials on a certain theme by an individual. Importantly, commonplace books are not diaries or journals, as they are structured thematically rather than chronologically, and do not necessarily relate to the personal lives of their compilers. By the 17th Century, commonplacing was prevalent enough to be formally taught at places such as Oxford University, and there is a strong tradition of literary figures such as John Milton, Mark Twain and Thomas Hardy compiling them.

There are two commonplace books belonging to Robert Burns in existence. The first, begun in 1783, was almost certainly not intended for publication, and entries cease in October 1785. The second, begun in Edinburgh in 1787 and sometimes referred to as the Edinburgh Journal, has many interesting entries including early versions of the Bard’s poems and musings on people he knew. On its first page, Burns explains his desire to record his experiences in Edinburgh (where he had just moved), and his observations on the people he has met, while they are still fresh in his mind. He quotes Gray, saying ‘half a word fixed upon… is worth a cart load of recollection’ showing his preference for the written word over memory.

Near the beginning of the Book, Burns starts a discussion relating to his patron, the Earl of Glencairn, and laments the fact that a man with little talent and high social status (the Earl) would naturally be treated with more respect than a man of genius but low social status due to an accident of birth. He says, with similar sentiment to his work ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ That’:

Imagine a man of abilities, his breast glowing with honest pride, conscious that men are born equal, still giving that “honor to whom honor is due”; he meets as a Great man’s table a Squire Something, or a Sir Somebody; he knows the noble landlord at heart pays gives the Bard or what- ever he is, a degree o share of his good wishes beyond any at table perhaps, yet how will it mortify him to see a fellow whose abilities would scarcely have made an eight penny Taylor and whose heart is not worth three farthings meet with attention and notice that are forgot to the Son of Genius and Poverty?

Burns does confess to being torn, however, because Glencairn was so pleasant to him when they met.

Also near the start of the book is a first draft of the song ‘Rantin’ Rovin’ Robin’ referring to the incident in which the gable end of Burns Cottage blew down during a storm in the first few weeks of Robert’s life. Interestingly, in this version, the opening line is ‘There was a birkie born in Kyle,’ as opposed to ‘there was a lad was born in Kyle’. There are then two versions of a poem written in Carse Hermitage on June 1st 1788, with a note beside the first draft instructing the reader to instead read the second draft further into the book. There is also a draft of his more famous poem, On seeing a wounded hare, along with other notes on his works.

Burns’s second commonplace book is on display in our museum collection and is a fascinating insight into some of the Bard’s personal thoughts, and also on how he drafted his poems. We wonder how many of our readers keep scrapbooks of this kind?

The ‘Heaven taught ploughman’?

‘Though I am far from meaning to compare our rustic bard to Shakespeare, yet whoever will read his lighter and more humorous poems, … , will perceive with what uncommon penetration and sagacity this heaven taught ploughman, from his humble unlettered station, has looked upon men and manners. – Henry MacKenzie

At the age of 6, a young Robert Burns was sent to school at Alloway Mill to be taught by a William Campbell. The Bard’s father, William Burnes, was a great believer in his children’s education and wanted to ensure they received proper schooling. Unfortunately this was to prove tricky as Campbell the village left shortly afterwards. Not to be deterred, William Burnes approached Ayr Grammar School and requested a private tutor, John Murdoch, to teach his boys alongside 4 other families in the village, and to take turns to board in each of their houses.

Murdoch was a young man of eighteen himself, but struck up a firm friendship with William and enjoyed teaching the boys. Even after the family left Burns Cottage, they continued to attend Murdoch’s school in the village for two years. At this point, Murdoch left the area, but returned in 1772 and taught Robert Burns further, particularly French and English grammar. He also gifted him the works of Alexander Pope, whom Burns quotes frequently in subsequent letters and admired greatly.

Gilbert Burns wrote extensively on his former teacher, and credits him with inspiring Robert’s love of reading:

‘With him we learned to read English tolerably well; and to write a little. He taught us, too, the English grammar; but Robert made some proficiency in it, a circumstance of considerable weight in the unfolding of his genius and character; as he soon became remarkable for the fluency and correctness of his expression, and read the few books that came in his way with much pleasure and improvement; for even then he was a reader when he could get a book. Murdoch, whose library at that time had no great variety in it, lent him the Life of Hannibal, which was the first book he read (the school-books excepted), and almost the only one he had an opportunity of reading while he was at school.’ – Gilbert Burns

Murdoch himself wrote of his time teaching the Burns boys, in which he was less than complimentary about the Bard’s singing abilities, and confesses that he would have thought Gilbert more likely to develop into a famous poet:

‘Robert’s ear, in particular, was remarkably dull, and his voice untunable. It was long before I could get them to distinguish one tune from another. Robert’s countenance was generally grave and expressive of a serious, contemplative and thoughtful mind. Gilbert’s face said, “Mirth with thee I mean to live”; and certainly if any person who knew the two boys had been asked which of them was most likely to court the Muses, he would surely never have guessed that Robert had a propensity of that kind.’ – John Murdoch

In 1776, a complaint was made against John Murdoch that he had insulted the local church minister, William Dalrymple, and the former was forced to leave the village. He moved to London, where he actually assisted with the funeral arrangements of Burns’s younger brother William, who he had met with shortly before William’s death. Unfortunately for Murdoch, he died himself in 1824 in extreme poverty.

Thanks to the determination of his father and the dedication of John Murdoch, Robert Burns received a considerable formal education in his youth. This fostered his love of literature, and allowed him to develop the social and political knowledge necessary for writing some of his greatest works. Far from being a ‘heaven taught ploughman’ as MacKenzie suggests in his review of the Kilmarnock Edition in 1786 (see top of blog), Robert Burns received excellent schooling for the time, and was able to put this to full use during his adult life.

A convenient convention

Our latest blog post was written by Visitor Services Assistant, Jim Andrews.

Access to rare books and manuscripts is generally only given by special arrangement to well qualified academics, who are only allowed to handle the originals very carefully while wearing clean white gloves. Today, however, digitised versions of rare documents can be viewed by anyone with a computer and access to the Internet. For Burns enthusiasts there is a digitised copy of an original Kilmarnock edition available in the digital gallery of the National Library of Scotland. It can be accessed on https://digital.nls.uk under the heading Literature & writers.

Seeing a copy of the original version of 1786 as printed by John Wilson can be a bit of a surprise, if it is your first time. It does not look quite right, not at all like any of the editions of Burns’s works you might find today. The reason for the unfamiliar appearance is the rather odd-looking spelling of some words: words containing the letter s. At the time of printing there were two versions of that letter in common use: a long one and a short one. The short one is the only one in use today: the long one looks confusingly like the letter f with a bit missing (the bar across the middle). The line Wee, ſleekit, cowran, tim’rous beaſtie shows how it was generally used. It appears at the beginning and in the middle of a word, but the short s is always used at the end of a word. That is a rough guide: there were some exceptions.

The disappearance of the long s in English was a gradual process that started during Burns’s lifetime towards the end of the 18th century. Between 1800 and 1820 it was well on its way out, and by the middle of the 19th century it had gone. According to an article about the long s in Wikipedia, you can use it to date early editions of Burns published in the 1780s and 1790s that may have lost their title page and year of publication. In these you will find the long s, but not in any of the 2,000 plus editions published after 1800.

In many countries spelling is controlled by government-sponsored organisations that determine what is correct and, from time to time, change their minds and alter or revise what is correct. English spelling has never endured any such official interference, but that is not to say it has not changed. Changes in English spelling have been brought about by the printing and publishing industry: a convenient convention that seems to work quite well. There is a story that the disappearance of the long s in English may have been set in motion in 1791 by the printer and publisher John Bell. It may be fanciful, but they say he dropped the long s because he did not like how it looked in his edition of Shakespeare’s plays.