Inspiration

We Get By With A Little Help From Our Friends

Friends of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum is a registered independent charity which was created in February 2013 to support the museum. Initially, the Friends group was set up in order to raise funds for the Burns Monument Restoration Appeal – this was a tremendous success, with the Friends donating £30,000 to the Burns Monument Fund in 2017, and a further £6000 donated in 2018. Since then, the Friends have continued to raise funds through a variety of means, and these are donated to the museum for use in other restoration and development projects.

The Friends fundraise in many different ways. Chief amongst them is the Garden Shop: in 2013, the Friends took over the old ticket kiosk in the Burns Monument Garden and set about converting it into a shop. Open during the summer season, the Garden Shop sells plants, bulbs and seeds, as well as Burns-related crafts, drinks and ice-creams to enjoy. Whilst the shop is closed throughout winter, the dedicated volunteers sell Christmas trees and wreaths during the festive season as well. Now in its seventh year, the Garden Shop is set to re-open in the very near future; it is opening later than usual due to work being done on the electronics within the shop.

A number of events also run throughout the year – for example, next month the Friends are putting on a Big Band Night at the museum, featuring the highly popular band That Swing Sensation. Further details can be found on the RBBM website. The Friends also hold an annual quiz night, as well as raffles and tombolas throughout the year.

Finally, it is thanks to the Friends of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, and in particular the Chair, Hugh Farrell, that the Burns Supper returned to the Burns Cottage. The first ever Burns Supper was held in July 1801, when nine friends of the late Robert Burns gathered in his childhood home to dine, read his poetry and deliver an ode to the Bard before raising a glass in his name. The suppers continued to be held in the Cottage until 1809, before moving to the King’s Arms Hotel in Ayr in 1810. After a gap of two hundred and seven years, on 25th January 2016, a Burns Supper was once again held in Burns Cottage. This event has become the Friends’ major fundraiser.

The Supper has been a regular event every year since and attracts guests from all over the world. The traditional order of a Burns Supper is delivered, complete with piper, fiddler, poetry recitals, songs, and, of course, haggis, neeps and tatties. The names of the nine gentlemen who attended that first supper are listed on the programme, as are the names of all performers and guests at the current supper; a copy of the programme is then placed in the museum archives to become part of the history of the cottage. Attendees at the Burns Cottage Supper are also lucky enough to interact with an object from RBBM’s own collection (with the curator watching closely nearby!). And each year, the Gregg Fiddle that Robert Burns learned to dance to is played: a magical moment.

The Friends of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum are an integral part of RBBM, and the work they do to fundraise for our restoration and development projects is invaluable. We would like to thank them endlessly for the contributions they have made so far, and we look forward to many more years working successfully with them to ensure as many people as possible can enjoy the birthplace of the Bard.

More information on the Friends can be found on their Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/friendsofrbbm/

Four Women Who Inspired Burns

In honour of Women’s History Month, throughout March the RBBM Facebook and Twitter have shared poems linked to influential women in Robert Burns’s life. We thought we’d round off the month with a blog exploring each of these ladies in more detail!

First up is Jean Armour, Robert’s wife. She was born 25th February 1765 in Mauchline, Ayrshire. Whilst growing up, Jean was renowned for her beauty and was part of a group of young women often referred to as ‘the Belles of Mauchline’. She met Robert when she was around eighteen, and less than two years later she was pregnant with his child – her father famously fainted when told that Robert was the father! He refused to allow the couple to marry – this meant he would rather Jean be a single mother than married to Robert, which speaks volumes about Robert’s reputation!

Despite this less than promising start to their relationship, Jean and Robert were formally married on 5th August 1788 – Jean’s father had come round to the idea after Robert’s poetry success. They had a mostly happy marriage, despite Robert’s famous infidelities – Jean herself said that he should have had ‘twa wives’.

Jean and her family moved to Dumfries in 1791 and this is where Robert died in 1796. Jean could not attend his funeral as she was in labour with their ninth child, Maxwell. Tragically, Maxwell died at the age of two – just four of the couple’s children survived to adulthood. However, Jean did also look after Betty Park (Robert’s child to Ann Park) and they had a good relationship. After Robert’s death, Jean never remarried, and she lived in the house they had shared in Dumfries until she died 26th March 1834 – she outlived her husband by thirty-eight years.

Next is Agnes Burnes, née Broun – the Bard’s mother. Agnes was born 17th March 1732 near Kirkoswald in Ayrshire. Her mother died when she was just ten years old; being the eldest sibling, it was then Agnes’s responsibility to care for the family until her father remarried two years later. However, Agnes and her new step-mother did not get on well, and Agnes was sent to live with her maternal grandmother in Maybole. She instilled in Agnes a great love for Scottish folk song and music.

Agnes met William Burnes (spelled differently but pronounced the same as ‘Burns’) in 1756 and they married on 3rd December 1757. They settled in the clay biggin William had built in Alloway; Robert Burns was the eldest of their seven children. It is thought that Agnes was a great influence on Robert’s own love of Scottish folk song and music, just as her grandmother had been to her. After William died in 1784, Agnes went to live with her son Gilbert. She moved around with his family until her death, at the age of eighty-seven, on 14th January 1820.

The third woman we featured this month is Frances Dunlop, a wealthy heiress almost thirty years older than Burns. Born 16th April 1730, her maiden name was Wallace, and her family claimed descent from William Wallace himself! Frances married at eighteen, when her husband, John Dunlop, was in his forties. They had a happy life together – however, John died in 1785. In the same year, Frances’s childhood home and lands were lost to the family. These incidents caused her humongous grief and she fell into a prolonged depression.

What finally roused her was Robert Burns’s poem ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’. She enjoyed reading it so much that she contacted Robert to ask for more copies and to invite him to her home – this began a long and friendly correspondence that lasted until the end of Robert’s life. Frances treated him almost like another son, praising his achievements and admonishing his indiscretions. She even offered advice on drafts of poetry and songs he would send her, the most famous of these being ‘Auld Lang Syne’! Although there was a two-year gap in their correspondence after Burns had offended Frances with some comments she deemed radical, Frances sent him a reconciliatory letter mere days before Robert’s death. She outlived him by nearly twenty years, dying 24th May 1815.

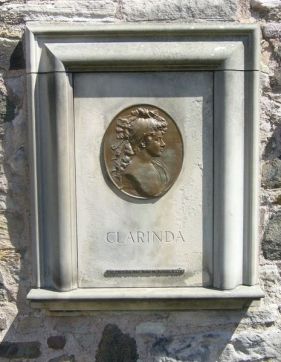

The last woman featured is Agnes Maclehose, aka the ‘Clarinda’ to Burns’s ‘Sylvander’. Agnes was born 26th April 1758 in Glasgow. She grew up to be a very articulate, well-educated and beautiful woman. She married at eighteen, but the marriage was an unhappy one and she separated from her husband in 1780.

Agnes met Robert Burns several years later at a party in Edinburgh – they were immediately taken with each other, and she wrote to him to invite him to tea at her home. Although an accident prevented this from happening, there began a long series of love letters and love poetry sent between the two. They used the pseudonyms ‘Clarinda’ and ‘Sylvander’. Despite the intensity of their correspondence, it is widely-thought that their affair was unconsummated. As Agnes was an incredibly pious woman and, although separated, still married, this makes sense.

In 1791 Agnes sailed for Jamaica to attempt to reconcile with her husband – however, he had started a family with another woman, so she returned to Scotland after only a few months. She met Robert for the last time in December of that year. For the rest of her life Agnes took great care of her letters from Robert, and after his death she even negotiated to have the letters she had sent to him returned to her.

In 1821 Agnes had tea with Jean Armour in Edinburgh. The two women, who could have been viewed as rivals of sorts, got on well and talked at length about their families, as well as their shared regard for Robert Burns. Agnes died twenty years later, at the age of eighty-three, on 23rd October 1841.

You can find the original Facebook and Twitter posts at https://www.facebook.com/RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum/ and https://twitter.com/RobertBurnsNTS.

Recipes for a Braw Burns Supper

Stuck for what to make for your Burns Supper later? Here at RBBM, we’ve got you covered. Below are some cracking recipes to get you out that inspiration rut.

Starting it off…

Given that Scotland’s got some of the best, why not kick off your Burns Night celebrations with some salmon? This smoked salmon pâté from Olive Magazine is a great option. Find it here.

Or maybe you want a soup to start? Both cullen skink or cock-a-leekie are classic (and delicious) options. This Nick Nairn recipe is sure to produce a show-stopping cullen skink – available here; and Tom Kitchin’s got you covered for a cock-a-leekie – available here.

Wee Beasties of the Glen

Of course, every Burns Supper needs a haggis to address! The great chieftain o’ the puddin race is much older than the man himself, but it’s on his birthday that most of us gather together to enjoy the dish.

Macsween have a hoard of fantastic recipes available on their website, many of which offer a wholly unexpected take on the humble haggis. One of our favourites are these Wee Beasties of the Glen’ – delicious bite-size haggis treats, coated in oatmeal and then fried. Find the recipe for these here.

Fortunately in these modern times, we can enjoy many different varieties including vegetarian, vegan, kosher and gluten-free – meaning everyone can help themselves to a plate of the good stuff!

Clapshot

You cannae have a Burns Supper without the neeps and tatties. But why not mix it up this year (literally) with a healthy serving of clapshot?

Originating from Orkney, this traditional dish combines both neeps and tatties, adding a wee bit of onion and some chives. Simple but delicious – clapshot is an excellent way to change up your usual Burns Supper.

Author of The Scots Kitchen, F. Marian MacNeill (a native Orcadian), has a traditional recipe for clapshot. You can find this – with a bit of history too – on the Scotsman’s Food and Drink page, here. If you’ve got any vegans at your table, you can swap out the butter for cooking oil.

Cranachan

A classic Scottish dessert – there’s nothing better than fresh raspberries after a hearty haggis meal. Top it all off (of course) with sweet honey, crunchy oats, a healthy dollop of cream and a swig of whisky.

Mary Berry’s take on cranachan is a winner, swapping the traditional crowdie for mascarpone – find her recipe here.

If you have any braw Burns Supper recipes of your own – we’d pure love to see them! Just don’t forget to finish your night off with a wee dram – it’s what Robert would want on his birthday.

‘The descendant of the immortal Wallace’

Throughout his life, Robert Burns was inspired by women. He grew up listening to the Scottish songs and folklore of his mother, Agnes, and distant cousin, Betty Davidson; fell in love time and again with a new bonnie lassie; and fathered several much loved daughters of his own who inspired his affections and poetry. Few relationships however are as well documented or as important to his works as his friendship with Mrs Frances Anna Wallace Dunlop, whose support and patronage were invaluable to the Bard for the majority of his publishing life.

Born in 1730, Frances Anna Wallace was the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas Wallace of Craigie and Dame Eleanora Agnew. Sir Thomas claimed to have been a descendant of Sir Richard, cousin of William Wallace – a connection which Burns was later delighted by. At the age of 17, Frances married John Dunlop of Dunlop and the couple went on to have 7 sons and 6 daughters. Their happiness was not to last however, as John died in 1785 resulting in Frances falling into a ‘long and severe illness, which reduced her mind to the most distressing state of depression’. This would have been an affliction Burns was also all too used to.

It was as she was recovering from this illness that a friend gave her a copy of The Cotter’s Saturday Night to read. So delighted was she with it that she sent, according to Gilbert Burns, ‘a very obliging letter to my brother, desiring him to send her half a dozen copies of his Poems, if he had them to spare, and begging he would do her the pleasure of calling at Dunlop House as soon as convenient’. The Bard responded by sending her 5 copies of his Kilmarnock Edition and a promise to call on her on return from his trip to Edinburgh. It was the start of a very important friendship.

Burns visited Mrs Dunlop at least five times throughout his life, and wrote more often to her than any other correspondent, sending her copies of his poems and drafts of letters intended for others. She in return wrote to him of her family troubles, as well as counselling him on career choices and urging him to modify what she described as his ‘undecency’ in relation to his affairs with women. She described his correspondence as ‘an acquisition for which mine can make no return, as a commerce in which I alone am the gainer; the sight of your hand gives me inexpressible pleasure…’ It would appear, in saying this, that she underestimated the value Burns placed on her friendship, as his increasingly desperate attempts to illicit a response from her after their falling out demonstrate.

This falling out occurred in 1794. With two of her daughters marrying French refugees and various members of her family having army connections, Mrs Dunlop had hinted at her disapproval of Burns’s apparent sympathies with revolutionaries in France in previous correspondence. He failed to take the hint and wrote in a letter of December 1794, referring to King Louis and Marie Antoinette, ‘What is there in the delivering over a purged Blockhead & an unprincipled Prostitute to the hands of the hangman, that it should arrest for a moment, attention in an eventful hour…?’ This offence was a step too far.

Burns sent Mrs Dunlop two further letters without reply, apparently completely oblivious to what could have caused her anger. ‘What sin of ignorance I have committed against so highly a valued friend I am utterly at a loss to guess’ he wrote in January 1796, ‘…Will you be so obliging, dear Madam, as to condescend on that my offence which you seem determined to punish with a deprivation of that friendship which once was the source of my highest enjoyments?’ On receiving no response, his final letter to her was sent just days before his death informing her that his illness would ‘speedily send me beyond that bourne whence no traveller returns’ and bestowing praise upon her friendship. It is believed that she did relent on receiving this, and one of the last things Burns was able to read was a message of reconciliation from her.

Mrs Dunlop survived the poet by another 19 years, dying in 1815. Her friendship and patronage were hugely valued by Burns, and her impact on the poet’s life and works should be regarded as just as important as that of other key women in his life. She is buried in Dumfries, Scotland but her words and thoughts live on in her letters to Scotland’s National Bard.

Was Robbie Radical?

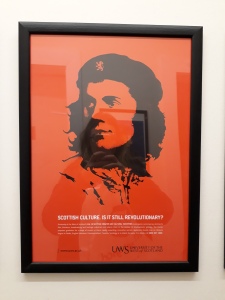

This iconic and vivid red poster definitely catches the een, however, at first glance you think you see the famous revolutionary Che Guevara in the Andy Warhol like pop art print – but, naw readers you’d be mistaken – its Robbie! Cleverly the University of West of Scotland have mischievously replaced Guevara’s face with Burns’s to stand as Scotland’s most well-known and well-loved revolutionary.

The posters purpose is to recruit students to study Scottish culture, and who best to represent that, than the greatest Scottish bard of all time. Popular culture ideas and images of Burns in the twenty-first century have made him a national favourite and his mug is surely recognizable by any true Scot. I mean he’s even got a national day after him (which outshines St Andrew’s day in Scotland!) An example of just how famous Burns is thought to be is conveyed in the pop art featured in the exhibition space of the RBBM.

Burns is seated at a dinner table next to the likes of Nelson Mandela, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Munroe and Mohammed Ali like a modern-day Jesus Christ hosting a Last Supper… all these celebrities are renowned for being extraordinary individuals and for revolutionizing their individual fields. But was Robert Burns revolutionary?

I wid argue, that through his works, he wis aye. The poems Scots Wha Hae, A Man’s a Man for a’ That and The Rights of Woman all are inherently radical based on their political subjects and they are full of powerful, and sometimes emotive, language.

Tyrants fall in every foe!

Liberty’s in every blow!

Let us do – or die!!

Tyrannical government was the object of American and European reformers and “liberty” was a 17th and 18th-century watchword.

Burns may not have been bodily present or involved in revolutionary activities but he was there in spirit and mind. His works are deeply imbedded with hope for change.

All in all, Burns has become the personification of Scottish identity and is a legend as his works and life are continued to be studied, celebrated and preserved the world over, hundreds of years after his death… If that doesnae make ye radical, then a dinny ken wit does.

By Parris Joyce

Burns and Books!

Today is the first day of Book Week Scotland, a national celebration of books and reading which takes place every year in November. Nearly everyone can say that they’ve been inspired by books at some point in their life, and Robert Burns was no exception. Thanks to William Burnes’s belief that his children should receive an education, and the diligence of the family’s tutor John Murdoch, Burns could both read and write. As a result of this, he was able to immerse himself in the various authors and poets who inspired him to become Scotland’s National Bard.

Robert himself, in an autobiographical letter to Dr John Moore, talks of two books that influenced him during his childhood:

‘The two first books I ever read in private, and which gave me more pleasure than any two books I ever read again, were, the life of Hannibal and the history of Sir William Wallace. Hannibal gave my young ideas such a turn that I used to strut in raptures up and down after the recruiting drum and bagpipe, and wish myself tall enough to be a soldier; while the story of Wallace poured a Scottish prejudice in my veins which will boil along there till the flood-gates of life shut in eternal rest.’

Evidence of that ‘Scottish prejudice’ can be seen in poems such as Scots Wha Hae, and Burns wrote many poems on the subject of war throughout his life, evidencing the impact both of these works had on him.

Gilbert – Robert’s brother – recalls one particular book which affected the future poet considerably, which was actually bought in error by their Uncle: ‘Luckily, in place of The Complete Letter-Writer, he got by mistake a small collection of letters by the most eminent writers… This book was to Robert of the greatest consequence. It inspired him with a strong desire to excel in letter-writing, while it furnished him with models by some of the first writers in our language’.

Robert wrote a great deal of letters throughout his life to his friends and family, and modelled many of them on letters that he read in this volume.

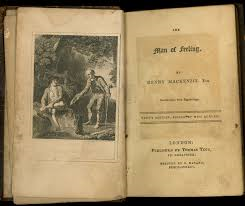

Burns read and was influenced by many more authors and poets throughout his life. He quoted Alexander Pope frequently, particularly in his early letters; described Henry MacKenzie’s ‘Man of Feeling’ as ‘the book I prize next to the Bible’; and perhaps most importantly was influenced by earlier vernacular poets such as Alan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson to write his poetry in Scots rather than English. There was however one book, or rather play, that certainly did not take his fancy – Titus Andronicus by Shakespeare. As he was about to leave for Dumfries, John Murdoch presented the Burns family with the play as a gift, but it proved too violent for the young Robert, who threatened to burn it if his tutor did not take it away again. Not all books are for everyone!

However you’re celebrating Scottish Book Week, whether it’s by picking up a new book for the first time, or by going back to an old favourite, we hope you enjoy wherever it may take you, and we hope it inspires you as much as Robert’s books inspired him!

Thrack Hooks

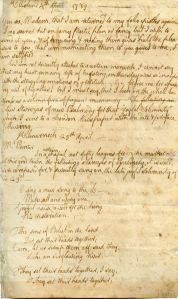

Thrack Hooks, or sickles, were used by the young Robert Burns as he went about his daily agricultural duties. Born into a farming family and raised on a smallholding until the age of seven, his upbringing not only earned him the nickname of ‘Ploughman Poet’, but hugely influenced his later works, probably inspiring the love of nature apparent in poems such as ‘To a Mouse’. Sickles were used during the harvest to chop the stems of crops such as barley, wheat and corn, and it was with thrack hooks that, in 1774, a fourteen year old Robert removed nettle stings from the hand of his work partner, a local girl and ‘bewitching creature’ probably named Helen Kilpatrick. This awakened in him a ‘certain delicious Passion’ and inspired him to write his first song: ‘O once I lov’d a bonnie lass’ or ‘Handsome Nell’. Burns’s modest upbringing caused him to doubt his abilities as a poet, but after learning that a local farmer had written a song about his sweetheart, he decided to try it out himself… and never looked back! Unfortunately for our Bard, the lady in question did not return his feelings and the poem was not written down until twelve years later, on this very manuscript.

It is now part of the Stair manuscript collection, a group of eight poems and songs Burns copied and sent to Mrs Alexander Stewart of Stair in 1786, and remains a lasting legacy of the farm girl who inspired Burns to write.