poetry

Celebrating Scots Language

As today is International Mother Language Day, our blog post explores the history of Scots language to celebrate and promote Scottish linguistic heritage.

Scots is descended from a form of Anglo-Saxon brought to the south-east of present day Scotland by the Angles (Germanic-speaking peoples) around AD 600. The video below, from The University of Edinburgh, illustrates the origins of Scots language.

Like many European countries, early Scots speakers primarily used Latin for official and literary purposes. The earliest surviving written poem in Scots, dated to 1300, is a short lyric on the death of King Alexander III (ruled 1249-1286) which appeared in Andrew Wyntoun’s work entitled The Original Chronicle:

“Qwhen Alexander our kynge was dede, That Scotland lede in lauch and le, Away was sons of alle and brede, Off wyne and wax, of gamyn and gle. Our golde was changit into lede. Crist, borne into virgynyte, Succoure Scotland and ramede, That is stade in perplexitie”.

Yet, the first Scots poem of any length called The Brus by John Barbour was recorded in 1375. Composed under the patronage of Robert II, this poem’s tale follows the actions of Robert the Bruce through the first war of independence.

The History of Scots from the 14th– 18th Century

Between the 14th and 16th century, writing in the vernacular thrived during the reigns of James III (ruled 1460-1488) and James IV (ruled 1488-1513): Scots language truly came into its own. This period’s Scots poets are known as medieval makars or master poets, after William Dunbar’s the Lament for the Makaris, for the great literacy culture that was produced in lowland Scotland. Dunbar was a virtuosic poet with an impressive range, varying from elaborate religious hymns to scurrilous bawdy verse.

Also a makar, King James VI (ruled 1567-1625) laid down a standard writers were expected to follow in his essay on literary theory entitled The Reulis and Cautellis. However, after James VI also became James I of England in 1603, Scots language and makars were no longer supported by the Royal Court. Pre-1603, James VI voiced the differences between English and Scots but now, as ruler of the British Empire, he attempted to Anglicise Scottish society for cultural, linguistic and political union of his kingdoms. Herein, the literary activity of 17th century Scots poets declined as many, like William Drummond of Hawthornden, decided to write in English instead. This change of language was encouraged by the Royal Court alongside the larger and more lucrative English publishing markets. In Scotland, all classes continued to write and speak in Scots but, for publications writers had their texts ‘Englished’.

The Great Scots Poets of the 18th Century

In the 18th century, under the 1707 Treaty of Union, Scotland joined England to form the new state of Great Britain and poets began to utilise an increasingly bilingual literary situation. Poets combined Augustan English poetry with Scots songs, tales and older poems to create a vernacular revival in Scots verse. The work of poets such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns demonstrated the popularity and poetic nature of Scots as a literature. These poets, expressing a national identity, produced poems that were, and continue to be, widely read.

Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) was born in Lanarkshire and educated at Crawfordmoor Parish School. Following his mother’s death, Ramsay moved to Edinburgh to study wig-making and eventually opened a shop near Grassmarket. He was an eminent portrait painter and began writing poetry from the early 1700s. In 1721, Ramsay published his first volume as a blend of English language and Scots poems. He abandoned the wig-making trade to become a bookseller, opening a shop near Edinburgh’s Luckenbooths- this also became Britain’s first circulating library. Ramsay’s works, such as Tea-Table Miscellany (1724), The Ever Green (1724) and The Gentle Shepard (1725), laid the foundations for Scot writers like Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns.

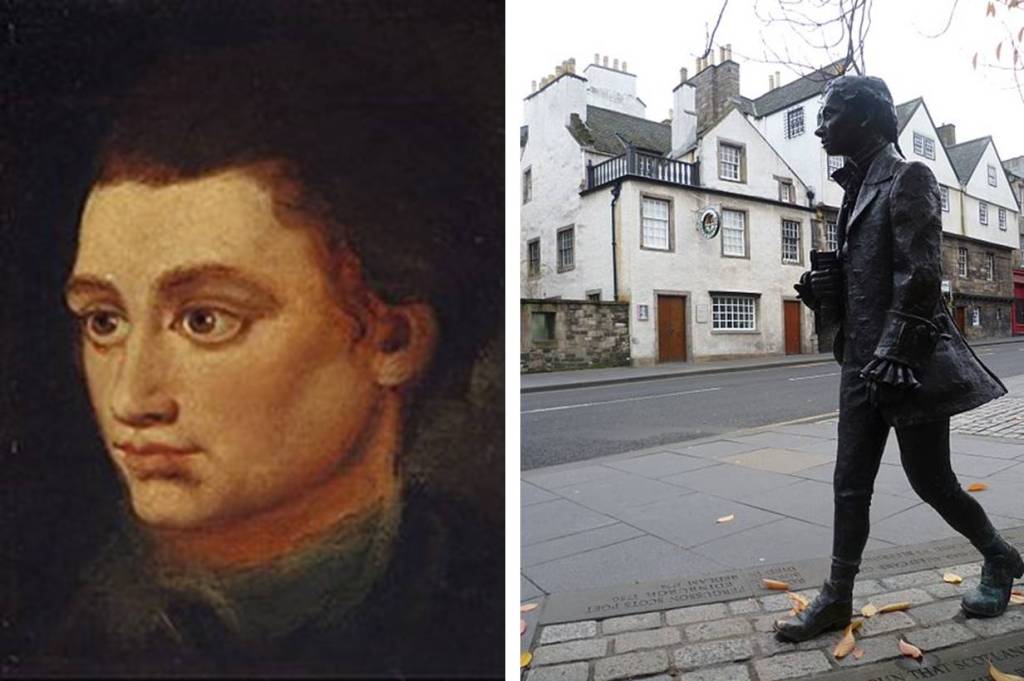

Robert Fergusson (1750-1774) was born in Edinburgh’s Old Town to Aberdeenshire parents. He attended St. Andrews University and became infamous for his pranks- for which he came close to expulsion. In 1771, Fergusson anonymously published his first trio of pastorals entitled Morning, Noon and Night. He amassed an exquisite range of about 100 poems, developing existing literary forms and contributing to contemporary debate. Aged 24, Fergusson experienced a fatal blow to his head falling down a flight of stairs, he was deemed ‘insensible’ and transferred to Edinburgh’s Bedlam madhouse where he later died. In 1787, Robert Burns erected a monument at his grave, commemorating Fergusson as ‘Scotia’s Poet’.

Robert Burns called Fergusson “my elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in muse”. Clearly inspired by the poet, Burns adopted both Fergusson and Ramsay’s use of Scots words and verse to master his own poetry and advance Scots literature. In doing this, Burns became Scots language’s most recognised voice with poems and songs read and sung worldwide. The Robert Burns Birthplace Museum displays volumes and poems by Fergusson and Ramsay (below), highlighting the similarities to Burns’ work in terms of tone, format, subject matter and, of course, Scots language.

The History of Scots Post-Burns to the Present

In the 19th century, building on the work of Scots poets, novelist began combining English and Scots in their writings. More often, English was used for the main narrative and Scots voiced Scots-speaking characters or short stories.

After this period, the 20th century saw a radical renaissance of Scots poetry, primarily through Hugh MacDiarmid (pen name of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid’s work The Scottish Chapbook, reassessed early Scots verse by using words from across different regions. Later, Edinburgh poet Robert Garioch reopened links to the Scots verse MacDiarmid devalued. Garioch, to a greater extent than MacDiarmid, developed a form of Scots united to any particular locality and produced a model that future writers could follow. Other 20th century poets, included Edwin Morgan, and his translation of Vladmir Mayakovsky’s poetry into Scots, as well as Tom Leonard’s Six Glasgow Poems.

Today, Scots language continues to thrive. In communities across Scotland, people use Scots as a language to write and speak. As the 2011 Scottish Census reported, there are 1.5 million speakers of Scots within Scotland, which is around 30% of the population.

So, why not challenge yourself? And join them? To celebrate Scots language and International Mother Language Day, learn a new word or a new phrase or more!

Check out the links below for more ways to learn Scots:

- On social media, we run a Scots word of the week campaign, encouraging our followers to guess and discuss what they mean. We often get international audiences commenting on the similarities between Scots and various European languages. Check it out on Facebook (@RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum) and Twitter (@RobertBurnsNTS).

- Search our blog for Scots language posts: https://burnsmuseum.wordpress.com/tag/scots-language/

- For Scots on Twitter, take a look at these pages: @lairnscots, @scotslanguage, @ScotsScriever, @tracyanneharvey @rabwilson1 and @TheScotsCafe.

- Join the Open University’s FREE online Scots language and culture course: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705

- Or, check out some of these websites: https://www.scotslanguage.com/

https://www.gov.scot/policies/languages/scots/

http://www.cs.stir.ac.uk/~kjt/general/scots.html

https://education.gov.scot/improvement/Documents/ScotsLanguageinCfEAug17.pdf

Gang oan, gie it an ettle!

English Poems Owerset intae Scots Leid!

Parris Joyce, Learning Officer fur the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, as pairt o Tracy Harvey’s recent Scots leid wirkshoaps, hus been owersettin some poetry intae Scots.

Owersettin is a gey gid way o engagin wae the leid an makin ye think haird aboot wit wirds wirk best. It’s a useful way o usin wirds ye already ken but micht o forgotten as weel as lairnin new yins tae.

Here is twa poems she owersit intae Scots. Enjoy!

The Walrus and the Carpenter by Lewis Carroll

(or The Muckle Flabby Selch an the Jiner)

The sin wis beekin oan the sey,

Beekin wae aw his micht!

He did his gey best tae mak

Tha billows sleekit an bricht –

An this wis unco, cause it wis

The middle o the nicht.

The muin wis beekin fungily,

Cause she thoucht tha sin

Hud goat nae business tae be thir

Efter tha day wis done –

‘It’s gey misbehadden o him’, she said,

‘Tae cum an tash the fun!’

The sey wis wet as wet cud be

The saunds were dry as dry.

Ye cuddnae see a clud, cause

Nae clud wis in the sky:

Nae burds wir fleein owerheid –

Thir wir nae burds tae fly.

The Muckle Flabby Selch an the Jiner

Wir daunerin nar at haun:

They gret lich ownyhing tae sei

Such quantities o saund:

‘If this wur only red oot’,

They said, ‘it wid be graund!’

If seeven lassies wae seeven besoms

Sweeped it fir hauf a year,

Dae ye reckin, the Muckle Flabby Selch spaikit,

‘Thit they cud git it red clear?’

‘I doot it’ said the Jiner,

An shed a wersh tear.

‘O Oysters, cum an dauner wae us!’

The Muckle Flabby Selch did fleetch.

‘A bonnie dauner, a braw blether,

Alang the briny beach:

We cannae dae wae mair thin fower,

Tae gee a haun tae each.’

The auldest Oyster luiked at hum,

But never a wird he said:

The auldest Oyster winked his ee,

And shoogled his heavy heid –

Meaning tae say he didnae choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But fower wee Oysters scrambled up,

Aw buzzin fir the treat:

Their jaikets were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat –

And this wis unco, cause, ye ken,

They hudnae any feet.

Fower ither Oysters follaeed thum,

An yit anither fower;

An thick an fast they came at last,

An mair, an mair, an mair –

Aw hoppin through the frothy waves,

And scrambling tae the shore.

The Muckle Flabby Selch an the Jiner

Daunered oan a mile or so,

An then they rested oan a rock

Conveniently low:

An aw the wee Oysters stood

An waited in a row.

The time has come, the Muckle Flabby Selch said,

To spaikit o mony hings:

O shoes – an ships – an sealing-wax –

O cabbages – an kings –

An why the sea is bilin hoat –

An whether sows hae wings.

But wait the noo, the Oysters gret,

Afore we huv oor chat:

Fir sum o us are oot o breath,

An aw o us are fat!

Nae rush! Said the Jiner.

They thanked him much fir that.

A loaf o breed, the Muckle Flabby Selch said,

Is wit we chiefly need:

Pepper an vinegar besides

Are gey guid indeed –

Now if yer ready, Oysters dear,

We cun stairt tae feed.

But naw oan us! The Oysters gret,

Turning a wee bit blue.

After such kindness, thit wid be,

A rotten hing tae do!

The nicht is braw, the Muckle Flabby Selch spaikit.

Do you admire the view?

It wis so kind of ye tae cum!

An ye are awfy nice!

The Jiner said nowt but

Cut us inither slice:

I wish ye werenae quite so deef –

I’ve had tae ask ye twice!

It seems a shame, the Muckle Flabby Selch spaikit,

To play them such a trick,

After we’ve broucht them oot so far,

An made them trot so quick!

The Jiner said nowt but

The butter’s spread too thick!

I greet fir ye, the Muckle Flabby Selch spaikit:

I deeply sympathize.

Wae sobs and tears he sorted oot

Those o the mucklest size,

Haudin his hanky

Afore his greetin eyes.

O Oysters, said the Jiner,

Ye’ve had a bonnie run!

Shall we be trotting hame again?

But reply came there nane –

An this was scarely unco, cause

They’d scoffed every yin!

Twas The Night Before Christmas by Clement C. Moore

(or Twis The Nicht Afore Yule)

Twas the nicht afore Yule,

when aw throu the hoose

Nae a beastie wis steerin,

nae e’en a moose;

The stockings were hung

by the lum wae care,

In houps thit St. Nic

soon wid be thir.

The weans were cooried

aw snog in their beeds,

While veesions o sugarplums

birled in thir heids;

An Maw in her mutch

an a in ma cap,

Had juist corried doon

fir a lang winter’s nap –

When oot oan the gairdin

there heaved such a clatter,

A boonced fae ma beed

to luik wit wis the matter.

Awa tae the windae

a fleed like a flash,

Teared open the shutters

an chucked up the sash.

The muin on the breist

o the new-fawen snaw,

Gave a lustre o twaloors

tae objeects ablow.

When, wit tae ma ferlie een

Shood kythe,

But a wee sleigh

An aucht wee Yule deer,

Wae a wee auld driver

so swippert an quick,

A kent in a blink

it must be St. Nick.

Mair fest than aigles

his coursers they came,

An he fussled, an rousted,

an cried them by name –

“Noo, Dasher! Noo, Dancer!

Noo, Prancer an Vixen!

Oan, Comet! Oan, Cupid!

Oan, Donder an Blitzen!

Tae the tap o the entry,

tae the tap o the wa!

Noo, hurl awa! Hurl awa!

Hurl awa aw!”

As dry leaves afore

the gallus hurricane flicht,

When they meet wae an obstacle

rise tae the lift,

So up tae the hoosetap

the coursers they fleed away,

Wae sleigh fu o thingamajigs –

an St. Nicholas tae;

An then in a glenting,

a heard oan the roof

The linkin an luifin

o each wee huif.

As a drew in ma heid

an wis birlin aroon,

Doon the lum St. Nicholas

came wae a boond.

He wis set-on aw in fur

fae his heid to his fut,

And his claes were aw tarnished

wae ashes and suit.

A haunfie o thingamajigs

he hud chucked oan his back,

An he luiked lik a peddler

juist opening his pack.

His een hoo they twinkled!

His dimples hoo mirkie!

His chowks were lik roses,

his neb lik a cherry!

His unco wee mou

wis drawn up lik a bow,

An the baird oan his chin

wis as fite as the snaw!

The stock o a gun

He held ticht in his teeth,

An the reek it encircled

his heid lik a wreath.

He hud a braid face

an a wee roon belly

Thit shoogled when he buckled

lik a bowlie fu o jelly.

He wis pluffie an sonsie –

a richt gawsie auld elf,

an a keckled when a saw him,

in maugre o masel.

A glimmer o his een

an a skew o his heid,

Soon gave me tae ken

A hud nowt tae dreid.

He spaikit nae a wird,

but when straucht tae his wirk,

An fillt aw the stockings

then birled wae a yerk,

An pittin his pinkie

aside o his neb,

An geein a nod,

Up the lum he fled.

He legged it tae his sleigh,

tae his fleeto gave a whustle,

An awa they aw flew

like the doon o a thrissel.

But a harked him goller

as he hurled oot o sicht,

“Joco Yule tae aw

an tae aw a gid nicht!”

Bards, Burns an Blether in The Bachelors’

It’s owre twa hunner year syne The Bachelors’ Club in Tarbolton saw the young Robert Burns an his cronies speirin aboot the issues o thaur day. It is therefore a braw honour tae gie this historic biggin a heize ainst mair by bein involved in organisin and hostin monthly spoken word an music nichts in the place whaur Robert Burns fordered his poetic genius, charisma an flair fir debate.

The Bachelors’ Club nichts stairtit in March this year eftir Robert Burns Birthplace Museum volunteer Hugh Farrell envisaged the success of sic nichts in sic an inspirational setting.

Tuesday the third o September saw the eighth session, an it wis wan we will aye hae mind o. Wullie Dick wis oor compère as folk favoured the company wi a turn.

Oor headliner wis Ciaran McGhee, singer, bard an musician. Ciaran bides an works in Embra an I first shook his haun some twa year syne at New Cumnock Burns Club’s annual Scots verse nicht. The company wis impressed then an agin at the annual “smoker” an at a forder Scots verse nicht. Ciaran traivelled doon tae Ayrshire tae play fir us, despite haen jist duin a 52 show marathon owre the duration o Embra festival.

Ciaran stertit wi a roarin rendition o “A Man’s a Man for a That”, an we hud a blether aboot hoo this song is as relevant noo, in these days o inequality an political carnage, as it wis twa hunner year syne, a fine example o Burns genius an insicht. Ciaran follaed wi Hamish Imlach’s birsie “Black is the Colour”, the raw emotion gien us aa goosebumps!! Ciaran also performed Johnny Cash’s cantie “Folsom Prison Blues”, an then Richard Thomson’s classic “Beeswing”, a version sae bonnie it left us hert-sair! Ciaran also performed tracks fae his album “Don’t give up the Day Job”.

The company wir then entertained by Burns recitals an poetry readins fae a wheen o bards an raconteurs. A big hertie chiel recited “The Holy Fair”, speirin wi the company on hoo excitin this maun hae buin in Burns day, amaist lik today’s “T in the Park”.

We hud “Tam the Bunnet” a hilarious parody o Tam o Shanter an Hugh Farrell telt us aboot the dochters ca’ad Elizabeth born tae Burns by different mithers, Burn’s first born bein “Dear bocht Bess”, her mither servant lass Bess Paton. Later oan cam Elizabeth Park, Anna Park’s dochter, reart by Jean Armour, an thaur wis wee Elizabeth Riddell, Robert an Jean’s youngest dochter wha deid aged jist 3 year auld. A “Farrell factoid” we learned wis that in Burns day, if a wee lassie wis born within mairrage, she was ca’ad fir her grandmither, if she wis born oot o wedlock she taen her mither’s first name. Hugh recited “A Poet’s Welcome To His Love-Begotten Daughter” fir us, the tender poem Burns scrievit, lamentin his love fir his first born wean, Elizabeth Paton.

We hud spoken word by various bards on sic diverse topics as a hen doo, a sardonic account o an ex girlfriend’s political tendencies, an a couthie poem inspired by a portrait o a mystery wummin sketched by the poets faither. In homage tae Burn’s “Poor Mailie’s Elegy”, we hud a lament in rhyme scrievit in the Scots leid, featurin the poet’s pet hen.

We learned o the poetess Janet Little, born in the same year as Burns, who selt owre fowre hunner copies o the book o her poetry she scrievit. This wummin wis kent as “The Scotch Milkmaid” an wis connected tae Burn’s freen an patron, Mrs Frances Anna Dunlop.

We also learned o hoo Burns wis spurned by Wilhelmina Alexander, “The Bonnie Lass of Ballochmyle” an hoo, eftir her daith, she wis foun tae hae kept a copy o the poem Burns scrievit fir her.

We hud mair hertie music fae Burness, performin Burns an Scottish songs sic as “Ye Jacobites by Name” an a contemporary version o “Auld Lang Syne” wi words added by Eddie Reader tae an auld Hebrew tune.

We hud “Caledonia” an “Ca the Yowes tae the Knowes” sung beautifully by a sonsie Auchinleck lass wha recently performed it at Lapraik festival in Muirkirk (oan Tibby’s Brig nae less!).

The newly appointed female president o Prestwick Burns Club entertained us on her ukelele wi the Burns song “The Gairdner wi his Paiddle” itherwise kent as “When Rosie May Comes in with Flowers”.

At the hinneren wi hud a sing alang tae Seamus Kennedy’s “The Little Fly” on the guitar an Ciaran feenished wi “Ae Fond Kiss”, interrupted by his mammy wha phoned tae see when he wis comin haim tae New Cumnock!

We hud sae muckle talent in The Bachelors’, that we didnae hae time fir a’body to dae a turn, so thaim that didnae will be first up neist time.

A hertie thanks tae a the crooners, bards an raconteurs an tae a’body in the audience fir gien up thaur time, sharin thaur talent an ken an gien sillar tae The Bachelors’ fund. Sae faur we hae roused £862 which hus been paid intae the account fir the keepin o The Bachelors’ Club.

Hugh Farrell is repeatin history by stertin a debatin group in The Bachelors’ on Monday 11th November, 239 year tae the day syne Burns launched it first time roon. Thaur will be a wee chainge tae the rules hooever, ye dinnae hae tae be a Bachelor an ye dinnae need tae be a man tae tak pairt!!

The Bachelors’ sessions are oan the 1st Tuesday o every month 7pm tae 10.30pm an a’body wi an enthusiasm for Burns is welcome.

Scrievit by Tracy Harvey, Resident Scots Scriever fir RBBM

We Get By With A Little Help From Our Friends

Friends of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum is a registered independent charity which was created in February 2013 to support the museum. Initially, the Friends group was set up in order to raise funds for the Burns Monument Restoration Appeal – this was a tremendous success, with the Friends donating £30,000 to the Burns Monument Fund in 2017, and a further £6000 donated in 2018. Since then, the Friends have continued to raise funds through a variety of means, and these are donated to the museum for use in other restoration and development projects.

The Friends fundraise in many different ways. Chief amongst them is the Garden Shop: in 2013, the Friends took over the old ticket kiosk in the Burns Monument Garden and set about converting it into a shop. Open during the summer season, the Garden Shop sells plants, bulbs and seeds, as well as Burns-related crafts, drinks and ice-creams to enjoy. Whilst the shop is closed throughout winter, the dedicated volunteers sell Christmas trees and wreaths during the festive season as well. Now in its seventh year, the Garden Shop is set to re-open in the very near future; it is opening later than usual due to work being done on the electronics within the shop.

A number of events also run throughout the year – for example, next month the Friends are putting on a Big Band Night at the museum, featuring the highly popular band That Swing Sensation. Further details can be found on the RBBM website. The Friends also hold an annual quiz night, as well as raffles and tombolas throughout the year.

Finally, it is thanks to the Friends of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, and in particular the Chair, Hugh Farrell, that the Burns Supper returned to the Burns Cottage. The first ever Burns Supper was held in July 1801, when nine friends of the late Robert Burns gathered in his childhood home to dine, read his poetry and deliver an ode to the Bard before raising a glass in his name. The suppers continued to be held in the Cottage until 1809, before moving to the King’s Arms Hotel in Ayr in 1810. After a gap of two hundred and seven years, on 25th January 2016, a Burns Supper was once again held in Burns Cottage. This event has become the Friends’ major fundraiser.

The Supper has been a regular event every year since and attracts guests from all over the world. The traditional order of a Burns Supper is delivered, complete with piper, fiddler, poetry recitals, songs, and, of course, haggis, neeps and tatties. The names of the nine gentlemen who attended that first supper are listed on the programme, as are the names of all performers and guests at the current supper; a copy of the programme is then placed in the museum archives to become part of the history of the cottage. Attendees at the Burns Cottage Supper are also lucky enough to interact with an object from RBBM’s own collection (with the curator watching closely nearby!). And each year, the Gregg Fiddle that Robert Burns learned to dance to is played: a magical moment.

The Friends of Robert Burns Birthplace Museum are an integral part of RBBM, and the work they do to fundraise for our restoration and development projects is invaluable. We would like to thank them endlessly for the contributions they have made so far, and we look forward to many more years working successfully with them to ensure as many people as possible can enjoy the birthplace of the Bard.

More information on the Friends can be found on their Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/friendsofrbbm/

Four Women Who Inspired Burns

In honour of Women’s History Month, throughout March the RBBM Facebook and Twitter have shared poems linked to influential women in Robert Burns’s life. We thought we’d round off the month with a blog exploring each of these ladies in more detail!

First up is Jean Armour, Robert’s wife. She was born 25th February 1765 in Mauchline, Ayrshire. Whilst growing up, Jean was renowned for her beauty and was part of a group of young women often referred to as ‘the Belles of Mauchline’. She met Robert when she was around eighteen, and less than two years later she was pregnant with his child – her father famously fainted when told that Robert was the father! He refused to allow the couple to marry – this meant he would rather Jean be a single mother than married to Robert, which speaks volumes about Robert’s reputation!

Despite this less than promising start to their relationship, Jean and Robert were formally married on 5th August 1788 – Jean’s father had come round to the idea after Robert’s poetry success. They had a mostly happy marriage, despite Robert’s famous infidelities – Jean herself said that he should have had ‘twa wives’.

Jean and her family moved to Dumfries in 1791 and this is where Robert died in 1796. Jean could not attend his funeral as she was in labour with their ninth child, Maxwell. Tragically, Maxwell died at the age of two – just four of the couple’s children survived to adulthood. However, Jean did also look after Betty Park (Robert’s child to Ann Park) and they had a good relationship. After Robert’s death, Jean never remarried, and she lived in the house they had shared in Dumfries until she died 26th March 1834 – she outlived her husband by thirty-eight years.

Next is Agnes Burnes, née Broun – the Bard’s mother. Agnes was born 17th March 1732 near Kirkoswald in Ayrshire. Her mother died when she was just ten years old; being the eldest sibling, it was then Agnes’s responsibility to care for the family until her father remarried two years later. However, Agnes and her new step-mother did not get on well, and Agnes was sent to live with her maternal grandmother in Maybole. She instilled in Agnes a great love for Scottish folk song and music.

Agnes met William Burnes (spelled differently but pronounced the same as ‘Burns’) in 1756 and they married on 3rd December 1757. They settled in the clay biggin William had built in Alloway; Robert Burns was the eldest of their seven children. It is thought that Agnes was a great influence on Robert’s own love of Scottish folk song and music, just as her grandmother had been to her. After William died in 1784, Agnes went to live with her son Gilbert. She moved around with his family until her death, at the age of eighty-seven, on 14th January 1820.

The third woman we featured this month is Frances Dunlop, a wealthy heiress almost thirty years older than Burns. Born 16th April 1730, her maiden name was Wallace, and her family claimed descent from William Wallace himself! Frances married at eighteen, when her husband, John Dunlop, was in his forties. They had a happy life together – however, John died in 1785. In the same year, Frances’s childhood home and lands were lost to the family. These incidents caused her humongous grief and she fell into a prolonged depression.

What finally roused her was Robert Burns’s poem ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’. She enjoyed reading it so much that she contacted Robert to ask for more copies and to invite him to her home – this began a long and friendly correspondence that lasted until the end of Robert’s life. Frances treated him almost like another son, praising his achievements and admonishing his indiscretions. She even offered advice on drafts of poetry and songs he would send her, the most famous of these being ‘Auld Lang Syne’! Although there was a two-year gap in their correspondence after Burns had offended Frances with some comments she deemed radical, Frances sent him a reconciliatory letter mere days before Robert’s death. She outlived him by nearly twenty years, dying 24th May 1815.

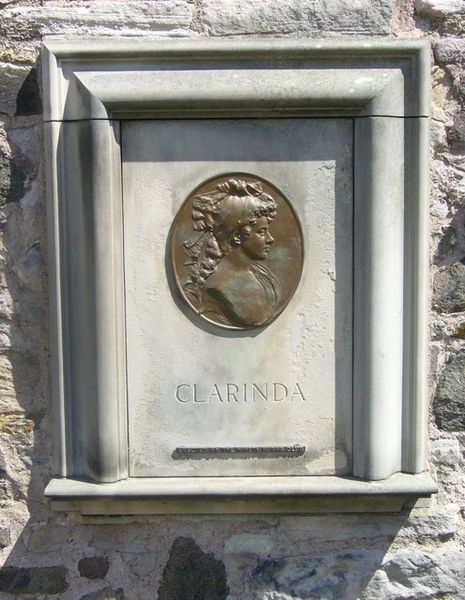

The last woman featured is Agnes Maclehose, aka the ‘Clarinda’ to Burns’s ‘Sylvander’. Agnes was born 26th April 1758 in Glasgow. She grew up to be a very articulate, well-educated and beautiful woman. She married at eighteen, but the marriage was an unhappy one and she separated from her husband in 1780.

Agnes met Robert Burns several years later at a party in Edinburgh – they were immediately taken with each other, and she wrote to him to invite him to tea at her home. Although an accident prevented this from happening, there began a long series of love letters and love poetry sent between the two. They used the pseudonyms ‘Clarinda’ and ‘Sylvander’. Despite the intensity of their correspondence, it is widely-thought that their affair was unconsummated. As Agnes was an incredibly pious woman and, although separated, still married, this makes sense.

In 1791 Agnes sailed for Jamaica to attempt to reconcile with her husband – however, he had started a family with another woman, so she returned to Scotland after only a few months. She met Robert for the last time in December of that year. For the rest of her life Agnes took great care of her letters from Robert, and after his death she even negotiated to have the letters she had sent to him returned to her.

In 1821 Agnes had tea with Jean Armour in Edinburgh. The two women, who could have been viewed as rivals of sorts, got on well and talked at length about their families, as well as their shared regard for Robert Burns. Agnes died twenty years later, at the age of eighty-three, on 23rd October 1841.

You can find the original Facebook and Twitter posts at https://www.facebook.com/RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum/ and https://twitter.com/RobertBurnsNTS.

Burns and his Wumin: The Attitudes to Women Found in Burns’s Poetry

As it’s Women’s History Month, one of the Learning Trainees here at RBBM, Caitlin Walker, has written about the attitudes to women found in Burns’s poetry. She has written the post in a similar way to how she would speak it, which is why there is a mixture of Scots and English language.

Maist folk know that Robert Burns enjoyed the company of women – his famous love affairs, the hundreds of poems and songs they inspired and the thirteen (that we know of!) weans he fathered attest to that. But what did he actually think of women?

Burns was born and lived his life during the latter half of the eighteenth century, a time when women couldnae vote and were rarely, if ever, formally educatit. Gender roles were strictly prescribed – for instance, women of the working class were given no formal education but taught how to run a hoose and look after a faimlie. Tasks were divided by gender completely, to the extent that women milked the coos but men mucked oot the byre, and during harvest time men used the scythe while women used the heuk. Women of higher classes would have learned literacy and maybe even another language or a musical instrument, but the expectation was the same – get merrit and raise a faimlie.

Different poems by Burns depict varying attitudes to women. For instance, ‘Willie Wastle’ – which is perhaps an unsuitably-named poem as it’s really about Willie Wastle’s wife – is hardly complimentary towards women. Burns describes her using terms such as ‘dour’, ‘din’, ‘bow-hough’d’ and ‘hem-shin’d’. She allegedly has ‘but ane’ e’e, ‘five rusty teeth, forbye a stump’, ‘a whiskin beard’ and ‘walie nieves like midden-creels’. Burns rounds off every stanza with the line, ‘I wad na gie a button for her’. This Burns is a far cry from the adorer of women the world recognises – he is being extremely disrespectful and takin nae prisoners in mocking her appearance!

This photograph shows the sign for the Willie Wastle Inn in Crosshill, Ayrshire. It depicts Willie’s wife as she is described in the poem.

This photograph shows the sign for the Willie Wastle Inn in Crosshill, Ayrshire. It depicts Willie’s wife as she is described in the poem.

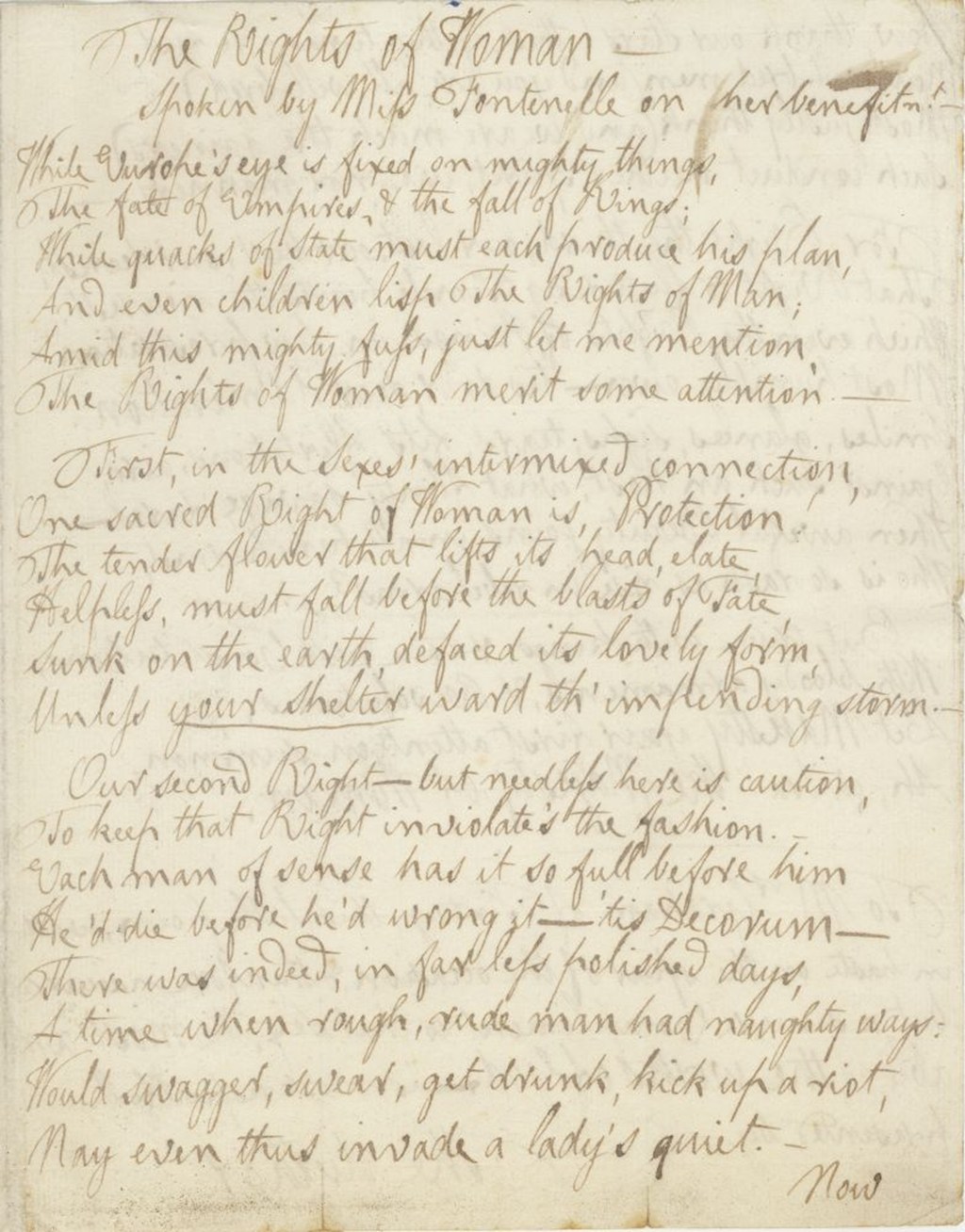

Contrast this with ‘The Rights of Woman’, Burns’s call for folk to remember the rights of women amongst the turbulent atmosphere of the eighteenth century, when ‘even children lisp the Rights of Man’. At first glance this seems like Burns being exceptionally forward-thinking for the 1700s – however, the ‘rights’ in question are: the right to protection, the right to decorum and the right to admiration. So really, Burns’s progressive rally for the rights of women is patronising and objectifying, which is a step up from outright insulting maybe, but still no brilliant.

This is a copy of ‘The Rights of Woman’ written by Burns in 1793 and sent to Mrs Graham of Fintry.

Then we have ‘It’s na, Jean, thy bonie face’ – and thank goodness! This poem is an outpouring of Burns’s love for his wife, Jean Armour – but crucially, it is ‘na her bonie face’ that he admires, ‘altho’ [her] beauty and [her] grace/ Might weel awauk desire’. Instead, it is her mind he loves. This shows Burns’s respect for Jean as a person with her own thoughts and desires. He goes on to say that even if he was not the one to make her happy, that someone would and that she’d be ‘blest’. He even says that he would die for her: this selfless desire to see her happy chimes much more with the image of Burns as the great lover of women that the world knows.

This photograph shows a case containing Jean’s wedding ring, as well as a ring containing a lock of her hair and a ring containing a lock of Burns’s.

Of course, cynics may just read ‘It’s na, Jean…’ as a soppy, hyperbolic gesture to get back in Jean’s good books – ye can make up yer ain mind.

A Fragment of History: Robert Burns’s Glossary Manuscript

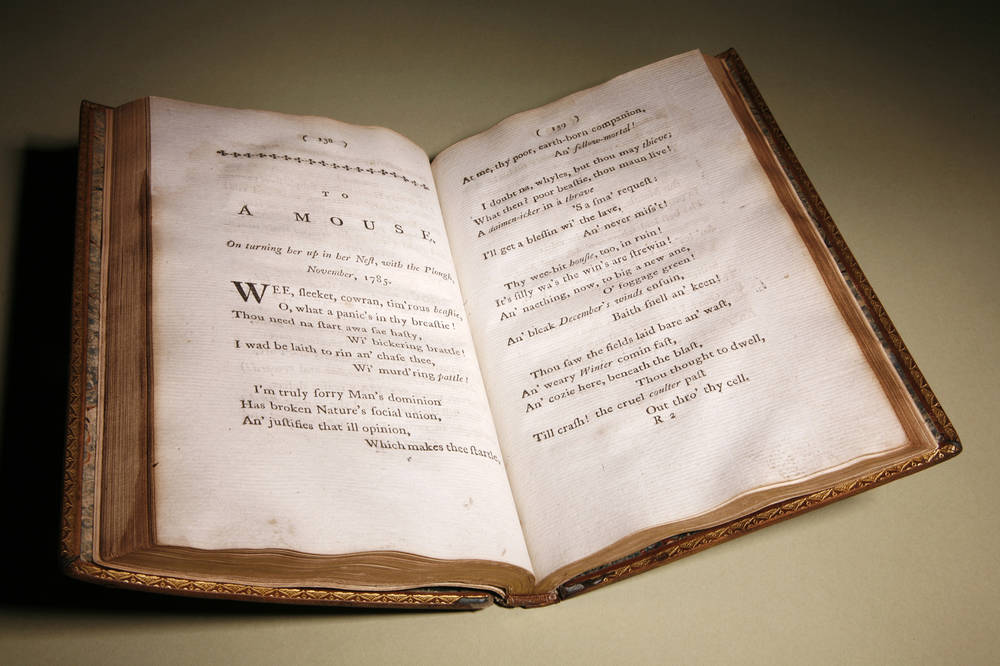

The second edition of Robert Burns’s poetry, known as the ‘Edinburgh Edition’ and published in 1787, contained a few differences from his first ‘Kilmarnock’ edition of 1786. For example, the Edinburgh Edition contained 22 more works, as well as a list of subscriber names and a 24-page glossary of Scots words. The collection at the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum contains a fragment of the original manuscript of this glossary:

Written by Burns himself in 1787, each entry has been subsequently scored out; this may have been as each was copied into a new, neater copy which itself has not survived. Words which Burns has glossed include ‘kaittly’, which means ‘to tickle’ or ‘ticklish’, ‘kebbuck’ which means ‘a (usually whole, homemade) cheese’ and ‘kelpies’, ‘mischievous Spirits that haunt fords at night’.

So why was Burns having to define words in his own native language to an audience of people who were also from Scotland?

The inclusion of the glossary is very indicative of the status of Scots language at the end of the 18th century. Since as far back as the Reformation in the mid-16th century, Scots had been subject to a great deal of anglicising influences – for example, English translations of the Bible, the removal of the royal court to London in 1603 and, of course, the Union of the Parliaments between Scotland and England in 1707. All of these influences meant that Scots had undergone a massive change in how it was written and also, we can probably assume, how it was spoken. Some Scottish people even went to elocution-style classes in order to eliminate ‘Scotticisms’ from their speech; Scots was seen as the language of the common people and therefore not fit for the ‘high’ subjects of politics, religion, culture or trade.

Burns was part of a tradition of writers who bucked this trend and started writing in Scots again. However, his Scottish audience were in need of a little assistance when it came to understanding some of the Scots words he used – hence, the glossary. Of course, Burns had fans out-with Scotland as well: before the 18th century was over, editions of his work had been published in Dublin, Belfast, London and New York. Audiences in each of these places would have needed plenty of help to understand Scots language as well.

Burns’s popularisation of Scots took inspiration from writers like Allan Ramsay (father of Allan Ramsay, the painter) and Robert Ferguson (Burns’s ‘elder brother in the muse’). Although the Scots was changed in some ways to make it more intelligible to non-Scots-speaking audiences – for example, inserting apostrophes where English versions of words would have other letters – it did mean speakers of other languages could understand and enjoy Scots literature and language.

The sheer stardom of Burns elevated people’s perception of it further, to the point where people across the globe sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ – a traditional Scottish folk song with words, in Scots – at Hogmanay. Although there is still a long way to go until Scots is back at the same level of recognition it would’ve been at in the early 16th century, campaigns by the Scottish Government and the work of contemporary writers in Scots show its well on its way there. Without Burns, and his predecessors, the Scots language would definitely be in a very different position nowadays.

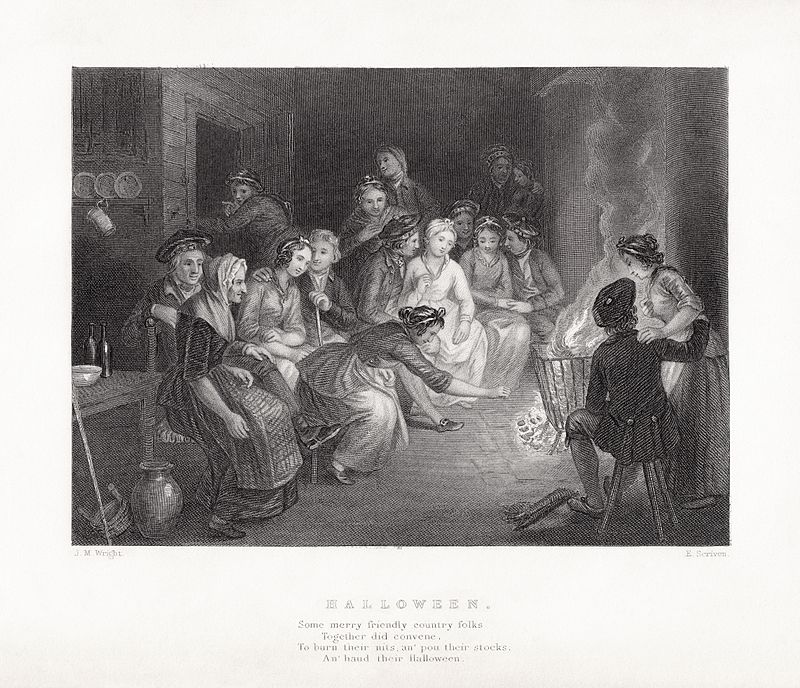

Halloween

Burns’s poem “Halloween” is a treat to read but a bit of a trick too…

Any reader from the twenty-first century would assume from the title that it is about the now widely celebrated commercial and secular annual event held on the 31st of October. Activities include trick-or-treating – or guising in the Scots language which Burns wrote in and promoted – attending costume parties, carving pumpkins into jack-o’-lanterns (or traditionally turnips in Scotland and Ireland – turnip is tumshie or neep in Scots), dooking for aipples, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories and watching horror films. However, the poem focuses on Scottish folk culture and details courting traditions which were performed on Halloween itself. Interestingly, it is widely believed that many Halloween traditions originated from ancient Celtic harvest festivals – particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain – and that Samhain itself was Christianized as Halloween by the early Church. Thus, there is obviously a deep-rooted connection between Scotland, its people and the celebration of All Hallows Eve.

The poem itself was written in 1785 and published in 1786 within Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect – or commonly known as the Kilmarnock Edition – because it was printed and issued by John Wilson of Kilmarnock on 31 July 1786. Although it focuses more on Scottish customs and folklore as opposed to superstition, Burns was interested in the supernatural. His masterful creation of “Tam o’ Shanter” is proof of that as well as his admittance in a letter written in 1787 to Dr. John Moore, a London-based Scottish physician and novelist, as he states:

‘In my infant and boyish days too, I owed much to an old Maid of my Mother’s, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity and superstition. She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the county of tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, inchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery’.

Burns in the first footnote writes that Halloween was thought to be “a night when witches, devils, and other mischief-making beings are abroad on their baneful midnight errands; particularly those aerial people, the fairies, are said on that night to hold a grand anniversary.”

Unlike Burns’s other long narratives such as “Tam o’ Shanter,” “Love and Liberty,” and “The Cotter’s Saturday Night,” “Halloween” has never enjoyed widespread popularity. Critics have argued that is because the poem is one of the densest of Burns’s poems, with a lot of usage of the Scots language, making it harder to read; that its cast of twenty characters often confounds the reader; that the poem’s mysterious folk content alienates readers who do not know anything of the traditions mentioned. Indeed, Burns felt it necessary to provide explanations throughout the poem. Only fourteen of Burns’s works employ his own footnotes. Of the fourteen footnoted works, “Halloween” outnumbers all others with sixteen notes of considerable length. The poem also includes a prose preface, another infrequent device used by Burns in only three other poems. The introduction for the poem states:

The following poem, will, by many readers, be well enough understood; but for the sake of those who are unacquainted with the manners and traditions of the country where the scene is cast, notes are added to give some account of the principal charms and spells of that night, so big with prophecy to the peasantry in the west of Scotland.

Indeed, the footnotes are most illuminating at detailing the intricacies of the rituals and are a crucial part of the poem. Some of my personal favourites are as follows:

[Footnote 5: The first ceremony of Halloween is pulling each a “stock,” or

plant of kail. They must go out, hand in hand, with eyes shut, and pull the

first they meet with: it’s being big or little, straight or crooked, is

prophetic of the size and shape of the grand object of all their spells-the

husband or wife. If any “yird,” or earth, stick to the root, that is “tocher,”

or fortune; and the taste of the “custock,” that is, the heart of the stem, is

indicative of the natural temper and disposition. Lastly, the stems, or, to

give them their ordinary appellation, the “runts,” are placed somewhere above

the head of the door; and the Christian names of the people whom chance brings

into the house are, according to the priority of placing the “runts,” the

names in question.-R. B.]

[Footnote 8: Burning the nuts is a favorite charm. They name the lad and lass to each particular nut, as they lay them in the fire; and according as they burn quietly together, or start from beside one another, the course and issue of the courtship will be.-R.B.]

[Footnote 10: Take a candle and go alone to a looking-glass; eat an apple

before it, and some traditions say you should comb your hair all the time; the

face of your conjungal companion, to be, will be seen in the glass, as if

peeping over your shoulder.-R.B.]

[Footnote 15: Take three dishes, put clean water in one, foul water in another, and leave the third empty; blindfold a person and lead him to the hearth where the dishes are ranged; he (or she) dips the left hand; if by chance in the clean water, the future (husband or) wife will come to the bar of matrimony a maid; if in the foul, a widow; if in the empty dish, it foretells, with equal certainty, no marriage at all. It is repeated three

times, and every time the arrangement of the dishes is altered.-R.B.]

Arguably, the poem has been appreciated more as a kind of historical testimony rather than artistic work. However, it is still a fascinating piece of poetry and definitely should be celebrated for its documentation and preservation of divination traditions and folklore customs which were performed on now one of the most widely celebrated festive days in Western calendars.

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)

Read the full poem here: http://www.robertburns.org/works/74.shtml

An Awfie Symbolic Seat

Date: 1858

Object Number: 3.4521

On display: in the museum exhibition space

This remarkable chair is made of wood sourced from the Kilmarnock printing press which produced the first edition of Robert Burns’s work Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect known as ‘The Kilmarnock Edition’. It was published on the 31st July 1786 at the cost of three shillings per copy. 612 copies were printed and the edition was sold out in just over a month after publication. The printing press no longer exists but in its stead there are two statues: one of Burns and one of John Wilson (the owner of the press) to commemorate the publication of Burns’s first works.

This chair was constructed in 1858, just before the Burns Centenary Festival in Ayr in 1859. The one hundredth year anniversary of the bard’s birth was celebrated far and wide by many. One contemporary counted 676 local festivals in Scotland alone, thus, showing the widespread popularity of Burns.

The chair has plush red velvet on the cushion and is elaborately carved with symbolism and references to some of Burns’s most loved works. Each arm rest ends with a carving of a dog, Luath and Caesar, from the poem ‘The Twa Dogs’.

A carving of Robert Burns himself, after the artist Alexander Nasmyth’s famous portrait – whereby he is shown fashionably dressed in a waistcoat, tailcoat and stalk – is placed in the centre at the highest point of the back of the chair with the infamous characters Tam and Souter Johnnie from the narrative poem ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ on either side. Thistles, commonly regarded as the floral national emblem of Scotland, decorate the gaps between the figures.

The central carving is of the climactic scene of Tam crossing the Brig o’ Doon atop of his trusty cuddie (horse in Scots) Meg with Nannie the witch at their heels. The Brig o’ Doon is actually a real bridge and is located in Alloway where Burns was born and lived for seven years.

A small plaque above this quotes a verse from Burns’s poem ‘The Vision’ which was written in 1785 and published in Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. It takes the form of a poetic ‘dream vision’, a form used in medieval Scottish verse and revived by Allan Ramsay in his own poem ‘The Vision’, from which Burns takes his title and was influenced and inspired by immensely. In the long narrative poem, Burns as speaker returns from a hard day in the fields and, after resting by the fireside, falls into a dream state in which he is visited by Coila, a regional muse. Coila (whom the speaker is clearly attracted to) addresses Burns, describing how she watched his development from a young age – thereby offering an imaginative reworking of Burns’s emergence as a poetic talent. She ends with a confirmation of his poetic mission and crowns him as bard. The striking thing here is the self-consciousness Burns displays about his position even this early in his career.

The inclusion of these particular carvings could be symbolism of the themes in which Burns explored most through his works: nature with the dogs representing this; the supernatural via the Brig o’ Doon scene; comradery through Tam and Souter Johnnie the “drouthy cronie” and the nature of the self and humankind through the quote from ‘The Vision’ and Robert Burns himself.

Interestingly, during a visit to Burns Cottage in 1965, the boxing legend Muhammad Ali was pictured sitting in this chair. Following this visit he was made an honorary member of Alloway Burns Club. If you are intrigued by this then please read a previous blog by volunteer Alison Wilson about an extraordinary meeting to do with this celebrity visit to Alloway here: https://burnsmuseum.wordpress.com/2016/06/13/memories-of-muhammad-ali/.

By Parris Joyce, Learning Trainee.

An Insight Into Ae Fond Kiss

Ae Fond Kiss is one of Robert Burns’s most famous love songs, one that outlines not the joy that love can bring but the acute pain of a broken-heart. It is moving, emotional and tender.

The song was written in 1791 and sent in a letter to Mrs Agnes McLehose (addressed as ‘Nancy’ in this instance). Burns met Agnes (1758–1841) in Edinburgh when she arranged an introduction to the bard by a mutual friend, Miss Erskine Nimmo. They engaged in an intense yet unconsummated love affair, largely through a series of passionate letters exchanged between the two.

Following Burns’s departure from Edinburgh in 1788, the bard’s relationship with Agnes suffered owing to his reunion with and eventual marriage to Jean Armour, not to mention an affair with Jennie Clow, Agnes’s maid, which resulted in a child. In 1792, Agnes returned to the West Indies at the request of her estranged husband (only to return after finding out he had started another family). Upon learning of her planned departure, Burns was inspired and sent her the heart-rending song Ae Fond Kiss. The song was first published in 1792 in James Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum (which can be seen on display at RBBM).

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever;

Ae fareweel, alas, for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

Who shall say that Fortune grieves him,

While the star of hope she leaves him?

Me, nae cheerful twinkle lights me;

Dark despair around benights me.

I’ll ne’er blame my partial fancy,

Naething could resist my Nancy:

But to see her was to love her;

Love but her, and love for ever.

Had we never lov’d sae kindly,

Had we never lov’d sae blindly,

Never met-or never parted,

We had ne’er been broken-hearted.

Fare-thee-weel, thou first and fairest!

Fare-thee-weel, thou best and dearest!

Thine be ilka joy and treasure,

Peace, Enjoyment, Love and Pleasure!

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever!

Ae fareweeli alas, for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

In the third verse, the speaker reflects upon his infatuation with Nancy, suggesting that he could not resist her charms. Notice how the emphasis is on her appearance rather than other attractions: “But to see her was to love her”. Nancy may have had a great personality, came from a respectable background but here the speaker is idealizing the external beauty only. This is classic Burns as he himself and some of his works do have undertones of machoism, for example, cheating on his wife and in Tam o’ Shanter with Kate at home ‘nursing her wrath’ whilst Tam is drunk, flirting with Kirkton Jean and eyeing up Nannie!

The language is relatively straightforward and is polished compared to some of Burns’s other poems in Scots. Scots pronunciations are used throughout – for example, ‘nae’ for ‘no’ and ‘weel’ for ‘well’. Scots terms are limited to ‘ilka’ for ‘each’ or ‘every’ in the fifth verse. Perhaps Burns’s reasoning for this is because Nancy was included in polite 18th century society in Edinburgh and would have spoken in English rather than Scots?

The heavily romanticized and iconic quote from this poem is:

But to see her was to love her;

Love but her, and love for ever.

This would make any romantic swoon but one should keep in mind that on a biographical level, Burns writes to Agnes long after their initial infatuation. We know that Burns had returned to his own wife and he had also got Agnes’ servant pregnant. Can we still see this song as a true outpouring of emotion? Or, should we see it as a carefully crafted piece of poetry? I think it is both – Burns had a tendency to have bursts of illogical emotion when it came to his love affairs, like confessing undying love to one whilst happily married to another, but that does not mean it was not real to him – but I do not think it matters either way you interpret it. It is what it is: and that is a beautiful love song.

In the main exhibition space within the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, there is a display case dedicated to Ae Fond Kiss which has four objects on display as well as an interesting contemporary interpretation of the work through images.

There are five snapshots taken from Hollywood movies that are about unrequited love: Romeo and Juliet, Casa Blanca, Gone with the Wind, Brokeback Mountain and Atonement. This reference to popular culture throughout the 20th and 21st centuries is a great way to convey how love and heart-ache has and always will be a topic of interest and an inspiration for artists no matter their medium.

Also, there is a teacup that belonged to Agnes which is used to represent the different social classes of Burns and her; a letter from Burns to Agnes saying he has included a song for publication (i.e. Ae Fond Kiss); another letter from Burns to Agnes in which they use their code names ‘Sylvander’ and ‘Clarinda’ because though separated, Agnes was deeply concerned with propriety and confidentiality; and Ae Fond Kiss shown in the Scots Musical Museum book.

Other objects within the museum’s collection which are worth noting are the silhouette miniature of Agnes, the pair of wine glasses Burns gifted Agnes and a letter from Agnes to Burns.

1878

Creator:

Alexander Banks Artist: John Miers,

Object No.:

3.8126

You can listen to a beautiful rendition of Ae Fond Kiss here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ax021N4iaFU

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)