Month: July 2018

Was He a Fighter too?

One of the main stereotypes on Robert Burns is that he was a womaniser; it is true he had many female companions in his lifetime. So with that in mind, was Burns a lover or a fighter? The truth is he was a bit of both, well let’s be honest, definitely more of a lover. Yet Burns was willing to fight for something he believed in, especially when it helped to keep him on the right side of the authorities. Consequently, while Burns was living in Dumfries he became a member of the local army unit, The Royal Dumfries Volunteers, and he was an active participant at its meetings and drill sessions.

So why did this widely known ‘lover’ join? Burns supported the principals of republicanism and he was not afraid to voice his controversial opinions to his friends around Dumfries. Unfortunately for him, his behaviour was noticed by his superiors at the Excise office. The recent revolutions in France and the American War of Independence had struck fear into the hearts of the British authorities. Therefore during this time of social and political unrest in the 1790s, the British government and Robert Burns’s employer did not look kindly on any revolutionist sympathisers. Despite this, Burns’s behaviour during this time is certainly questionable. For example, in October 1792 at the Theatre Royal in Dumfries, Burns was seen singing along to the French revolutionary song Ça Ira with a group of radicals. In addition to this he purchased four carronades (cannons) from a public auction, which he later donated to the French Legislative Assembly. For a highly educated and politically interested man, these actions lacked forethought and astuteness.

As a result of this Burns needed to do some ‘grovelling’ as it were, to get back into the good graces of his superiors. In order to prove his loyalty to the British Crown and save his desperately needed position at the Excise; Burns took an Oath of Allegiance and signed the Rules, Regulations and By-Laws on the 28th March 1795 to join the Volunteers. To further prove his allegiance to the British authorities, Burns wrote a song in April 1795 called Does Haughty Gaul Invasion Threat? (more commonly known as The Dumfries Volunteers). The song praises the recently formed Royal Dumfries Volunteers, whose duty was to defend Britain from a French attack. This however did not stop him from writing revolutionary poems and letters anonymously; after all, even this song’s last line is ‘We’ll ne’er forget The People!’

Although he never lost or completely put aside his politically radical thoughts, Burns proved himself to be a committed and hardworking Private in the Royal Dumfries Volunteers. This was not merely an empty gesture to the authorities; he worked hard to fulfil his duties. Burns attended the training sessions, which often lasted for two hours twice a week. He also served on the committee for three months from August 1795, which involved supplying the corps with weapons and other necessary equipment. Furthermore, unlike many of his comrades in the unit he was never fined for absenteeism, drunkenness or insolence. These duties and additional responsibilities were supplementary to his tiring job as an exciseman and a poet. Nevertheless he took them very seriously for the year and half he served with the Dumfries Volunteers.

His position and dedication to the Volunteers is evident, even though so little of his military career is now considered. On the day of his funeral it was not his writing that had the most pervasive presence, but his military career instead. His volunteer uniform, hat and sword rested upon the coffin, which was carried from his home to his final resting place in St Michael’s Churchyard. On Monday 25th July 1796, Burns received a military funeral that included the Dumfries Volunteers, the Cinque Port Cavalry and the Angusshire Fencibles. His comrades from the Volunteers were the pallbearers for his coffin, while the Cinque Port Cavalry band played Handel’s solemn Dead March from Saul. The slow procession moved in time to the music and the occasional toll of the great Church Bells until they reached the graveyard. The funeral party formed two lines and the coffin was carried between them to the grave. Although there are claims that Burns’s dying words were ‘don’t let the awkward squad fire over me,’ three volleys were fired over the coffin when it was deposited into the earth.

St Michael’s Churchyard, Dumfries

St Michael’s Churchyard, Dumfries

This truly was a grand spectacle, a fitting ceremony to represent the general regret and sorrow at Robert Burns’s passing. If Robert had not joined the Royal Dumfries Volunteers, would his funeral have been a much quieter affair? Would such an impressive ceremony have been awarded to him, if he had been just an exciseman and poet? We will never be able to answer those questions, but it is interesting that the job we least associate with Burns, is the one that played a defining role in his funeral. Days after his passing, death elegies began pouring out, as people across the country wanted to pay tribute to Scotia’s Bard.

Does Haughty Gaul Invasion Threat?

Does haughty Gaul invasion threat?

Then let the louns beware, Sir!

There’s wooden walls upon our seas,

And volunteers on shore, Sir!

The Nith shall run to Corsincon,

And Criffel sink in Solway,

Ere we permit a Foreign Foe

On British ground to rally!

O let us not, like snarling tykes,

In wrangling be divided,

Till, slap! come in an inco loun,

And wi’ a rung decide it!

Be Britain still to Britain true,

Amang oursels united!

For never but by British hands

Maun British wrangs be righted!

The Kettle o’ the Kirk and State,

Perhaps a clout may fail in’t;

But Deil a foreign tinkler loun

Shall ever ca’a nail in’t.

Our father’s blude the Kettle bought,

And wha wad dare to spoil it;

By Heav’ns! the sacrilegious dog

Shall fuel be to boil it!

The wretch that would a tyrant own,

And the wretch, his true-born brother,

Who would set the Mob aboon the Throne,

May they be damn’d together!

Who will not sing “God save the King,”

Shall hang as high’s the steeple;

But while we sing “God save the King,”

We’ll ne’er forget The People!

By Learning Trainee Kirstie Bingham

Goudie’s Dazzling Tam o’ Shanter Paintings

Tam o’ Shanter is Robert Burns’s masterpiece. A long, narrative, epic poem written in 1790 by Burns whilst living at Ellisland Farm, Dumfriesshire and published in Captain Francis Grose’s Antiquities of Scotland in 1791. Burns apparently wrote this in only one night and it appeared in the book just as a footnote! Now Burns was known to have enjoyed superstitious, supernatural stories as a child. His Aunty- a Betty Davison – told him many and Burns said that“[she] had, I suppose, the largest collection in the country of tales and songs, concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, inchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery.”[1] The poem is full of wild scenes, dramatic and exciting twists and turns, bloody and gothic content as well as witty machoism through the characters and their antics.

Many artists have been inspired by the poem and some of the artwork produced really brings the poem to life. Some of the most expansive and impressive works are that of Alexander Goudie. He was apparently totally obsessed by Tam o’ Shanter and his lifelong aim was to create 54 complete cycles of images inspired by the epic tale. He accomplished this and the results are spectacular. A select few will be shown and analysed below.

This painting refers to the first two lines of the poem:

When chapman billies leave the street,

And drouthy neibors, neibors meet;

This scene is full of vibrant colours, objects and action: Tam looks well, as does Meg, and they are surrounded by other animals and people greeting them warmly. It is arguably one of the best paintings in the cycle as it has been painted with such attention to detail. This could reflect that this is the part of the poem before Tam boozes at the nappy, thus, he is not intoxicated and he will have a clearer vision now compared to the rest of the poem. The reflection in the window is very life-like as is the woman pulling the curtain aside to have a good nosey at what is happening on the street. It is worth noting that this painting is number twelve – even though it refers to the first two lines of the poem – so Goudie has used his artistic licence and imagination to fill in the gaps of what happened before this point as well as not putting the images in order according to the lines of the poem i.e. No. 11 “As market days are wearing late” is the line after No. 12 “And drouthy neibors, neibors meet” but it comes before it in the cycle.

This of course refers to the beautiful and philosophical extract:

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed;

Or like the Borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the Rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.

This is typical Burns: returning to nature which is his greatest source of inspiration. In the painting Goudie has shown a scene that is a delicate paradise. A moment captured in time with two lovers lying in a field, with the man picking a poppy, and the rainbow overhead. This is very contradictory to the shock and horror that is to follow…

This is one of three images that are in black and white; although this one here has Tam’s clothes clearly visible, with the famous blue tam hat and yellow waistcoat drawing the eye, which isolates him even more so. The crack of lightning has inspired the use of black and white and Goudie has depicted a truly spooky scene with the trees looking ghostly bare and the town and bridge totally empty. It is preparing the viewer for what is about to come next…

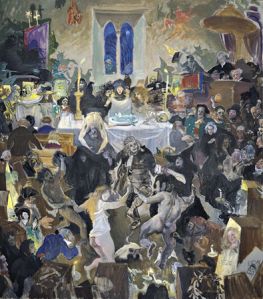

This is one of the treasures of the collection. It depicts the chaotic and shocking scene Tam beholds once he has approached the kirk: as a viewer you do not know where to look as it is so full of action and faces. This refers to the below section of the poem which is full of vivid imagery:

Warlocks and witches in a dance:

Nae cotillion, brent new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

A winnock-bunker in the east,

There sat auld Nick in shape o’ beast;

A towzie tyke, black, grim, and large,

To gie them music was his charge:

He screw’d the pipes and gart them skirl,

Till roof and rafters a’ did dirl.

Coffins stood round, like open presses,

That shaw’d the Dead in their last dresses;

And ( by some devilish cantraip sleight)

Each in its cauld hand held a light.

You can clearly see the devil glowering in the back corner, with his bagpipes in hand and mouth, casting a huge shadow on the back wall; the witches and warlocks are in a dance spinning each other around; the numerous coffins encircling the dancers with their skeletons holding candles as light. There is nakedness; there is sorcery going on at the table; the full moon can be seen through the window and the party-goers are oblivious to Tam’s presence.

This is another gem of the collection which is similar in the colour and the grotesque but exciting scene depicted as No.31. Tam and Meg are at the mouth of hell itself about to be devoured by the bright flames and are surrounded by all sorts of characters and mythical creatures who are all armed with weapons. Interestingly, the priest and lawyer are present, this inclusion of was famously shocking of Burns back in the eighteenth century. This is a scene which Tam and Meg did not actually suffer but it is a prediction – an insight into the future – of what will happen if they do not escape the ghoulish mob.

This is the moment which Nannie latches onto Meg’s tail just before they get to the key-stone. It refers to this section of the poem:

Now do thy speedy utmost, Meg,

And win the key-stane o’ the brig:

There, at them thou thy tail may toss,

A running stream they dare na cross.

But ere the keystane she could make,

The feint a tale she had to shake!

For Nannie, far before the rest,

Hard upon noble Maggie prest.

And flew at Tam wi’ furious ettle;

But little wist she Maggie’s mettle!

Ae spring brought off her master hale,

But left behind her ain grey tail:

The carlin claught her by the rump,

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

What I like about this interpretation most is that Tam is positively terrified, not composed at all, and has come off his saddle and is hanging around poor Meg’s neck. Tam o’ Shanter has a bit of sexism in it with all the drinking, men will be men, flirting with the barmaid whilst the wife is at home worrying drama in it but here Goudie has depicted Tam as being utterly at the mercy of a powerful female character: more so than as how Burns depicted him as Goudie has him literally hanging on for dear life.

This final image is in reference to the conclusion of the poem:

Now, wha this tale o’ truth shall read,

Ilk man and mother’s son, take heed:

Whene’er to Drink you are inclin’d,

Or Cutty-sarks rin in your mind,

Think! ye may buy the joys o’er dear;

Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mare.

Here Goudie has used his artistic licence again to create the scene he must have imagined when reading this ending. With only Tam and Meg in the painting: your sole focus is on them. Tam looks haggard, totally drained and panting heavily with his tongue sticking out. He looks like he has aged ten years form his traumatic experience. Meg – the hero of the poem – has also suffered this dramatic change same as Tam. Yes, her tail is gone with only the bloody stump left but she looks aged, thin – bony even – and is cowering by Tam with her head down in fear and she has soiled herself. Altogether, it is not a pretty sight, but a great visualisation of the moral warning in which the poem ends.

All of these paintings are now in the collection of Rozelle House Galleries (and some are on permanent display). This is situated in a historic mansion, surrounded by beautiful grounds and also boasts a tea room too. It is just a two minute drive away from the Burns Cottage and only six minutes from Ayr town centre. I would thoroughly recommend any art or Tam o’ Shanter lover to visit.

By Parris Joyce, Learning Trainee

[1] The Bard by Robert Crawford, p20

Useful link: