Month: March 2015

Mrs Rabbit’s Carrot Cake

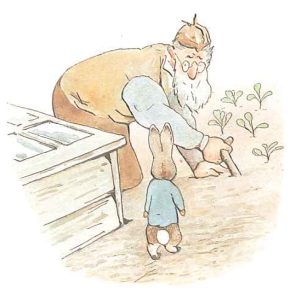

For this year’s Cadbury’s Easter Egg Trail we are celebrating the wonderful stories by Beatrix Potter. For me that is just a marvelous excuse to do some baking! From Peter Rabbit’s forays into Mr M

cGregor’s garden it is clear that he has some what of penchant for carrots. And what better way for Mrs Rabbit to make use of the carrots, than to make a delicious carrot cake!

Ingredients

Cake

2 cups self raising flour

1 teaspoon bicarbonate of soda

6 Eggs

300g melted butter

1 and 1/2 cups soft brown sugar

2 large carrots grated

Handful of raisins

Handful of chopped walnuts.

Teaspoon cinnamon

Teaspoon nutmeg

Cream Cheese Icing

280g full fat cream cheese.

280g softened butter.

Icing Sugar (1 cup or to taste)

Process:

In a bowl seive the flour and bicarbonate of soda. Add in the nutmeg and cinnamon and stir until combined.

Crack the 6 eggs into a separate bowl, with the brown sugar and melted butter. Whisk until mixture becomes thick and creamy.

Taking about a quarter at a time, fold the flour mixture into the wet ingredients until fully combined.

Fold in grated carrots.

Take a handful of raisins and a handful of chopped walnuts and fold those into the mixture.

Dollop mixture into two round cake tins. Remember to grease and line your tins or the cake will stick!

Cook in the oven for roughly 30 mins at 180c. You will know it is done if a toothpick inserted into the middle comes out clean, and if the sides of the cake are pulling away from the tin.

Place on a rack to cool.

Icing

With an electric whisk cream butter in a bowl until smooth and free of lumps.

Add in the cream cheese and whisk the two together until combined and free of lumps.

Add in icing sugar until it has reached your preffered sweetness.

Refigerate for several hours.

Assemblage

Put one of the cakes on a plate and coat the top with icing. Place the second cake on top and coat again with the icing. For decoration scatter some more walnuts.

Voila!

The Real Face of Burns

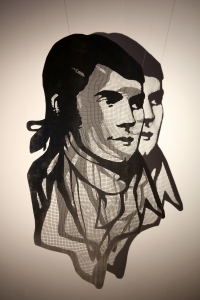

The range of interpretations of Robert Burns in The Real Face Burns shows us the variety of influences the poet has had in the past centuries. With artworks including new interpretations and ones which relate to more familiar ones the exhibition provides a vast insight into the representations of our bard.

I particularly like the variety of media used by the different artists: pin-heads, steel, gold leaf, ceramics, gesso, graphite and Indian ink. All the different processes of production are also very interesting: there are drawings, paintings, lego toys and photographic prints.

Facial depiction produced by Prof Caroline Wilkinson, Dr Chris Rynn, Caroline Erolin and Janice Aitken from the University of Dundee

The exhibition features works from world-famous artists, including To See Ourselves as Others See Us (b&w) and To See Ourselves as Others See Us (colour), by Graham Fagen (who is representing Scotland at the 2015 Venice Biennale). We have a life size model of Burns’ head, which was reconstructed using Burns’ skull and silhouette images of the poet, by forensic scientists at the University of Dundee. David Begbie’s Burns is a painted steel piece which represents an image of the poet that visitors familiar with him would recognise. The artist plays with space by lighting the sculpture strategically, creating a unique viewing experience!

Another artist who uses an interesting technique is Shannon Laing, who explains her piece The Young Ploughman Poet by stating: ‘Using other artists’ representations of what Burns may have looked like, in addition to descriptions of his appearance, I took photographs of men with similar features to Burns in a photographic studio under continuous lighting conditions. I then used photo editing software to combine these particular features to create a single face, and used this amalgam as a reference for my final graphite portrait.’ However, my personal favourite doesn’t feature Burns’ face at all. Tom Gallant’s To gie them music was his charge is an example of how folk culture paired with literary and social history can provide inspiration to contemporary artists. This work is made from cut paper and collage. Overall The Real Face of Burns is an incredibly inspiring exhibition featuring some of Scotland’s most prominent and emerging artists. Well worth a visit!

Elena Trimarchi – Learning Intern

The exhibition will be running until Sunday 14th June, entry is free with admission to the Museum.

The Inspirations of Burns and Beatrix

Robert Burns was not just a great poet; he was also an avid reader. Remembered by many as a lad who loved his books so much he would read at the table, we have honoured this with an artwork by Su Blackwell that represents his favourite childhood book: The Life of Hannibal. Regarding this book, Burns was to say: ‘Hannibal gave my young ideas such a turn that I used to strut in raptures up and down after the recruiting drum and bagpipe.’

We all remember books like this that inspired us when we were children and which have special places in our hearts. To celebrate this, each Easter we focus on a specific children’s author. This year we have selected Beatrix Potter, whose books have become some of the earliest stories we are introduced to. However, we haven’t selected Potter merely due to her fame, but also due to her love of the countryside.

Both Burns and Potter were inspired by the Scottish countryside and by the people they met there. For Burns, the Ayrshire he grew up in became his muse, but for town-bred Beatrix, her family holidays in Perthshire were to be a revelation. Staying with her family at Dalguise House, a young Beatrix honed her artistic skills in hours of painting and sketching. This in adulthood would earn her good money – not only through her stories – but through commissions for scientific illustrations. While the Lake District was the place Potter was to ultimately make her home, it was Perthshire again which helped her make her mark. On holiday with her rabbit in a house owned by a Mr McGregor, Beatrix sent a ‘picture letter’ to a friend’s son with a story of four rabbits: Flopsy, Mopsy, Cotton-Tail, and Peter. Like Burns, Potter also creates characters for the animals and people that surround her. While Burns immortalised Souter Johnnie, Potter turns local washer woman, Kitty MacDonald, into Mrs Tiggy-Winkle –a mysterious washer of pocket handkins and pinnies.

So come along to the museum from Friday 3rd to Monday the 6th of April, and see Burns Cottage transformed and alive with with inspiration from Peter Rabbit’s world. Take part in our Cadbury’s Peter Rabbit Easter Egg Trail and you’ll make the day even better with some delicious chocolate!

To Agnes Burnes, For Mother’s Day

In celebration of Mothers Day this Sunday, it seems appropriate that this week’s blog post should be dedicated to Robert Burns’s mother, Agnes.

The first of six children, Agnes Brown was born in March 1732 in Kirkoswald, Ayrshire, the daughter of Agnes Rennie and Gilbert Brown. However, as was tragically far too often the case, Agnes’s mother died, leaving a ten year old Agnes to keep the house and look after her younger siblings. Two years later, when her father remarried, this responsibility was lifted from Agnes’s shoulders as she sent to live with her maternal grandmother, Mrs Rennie. As to whether this arrangement was one that had been decided amiably, or was the result of a family argument, we are sadly in the dark, but for the next thirteen years Maybole was to become the home of Agnes Brown, and Mrs Rennie, her family.

In Maybole Agnes was to have two main romances. The first one was with ploughman William Nelson, but a long seven year engagement ended, perhaps due to improper actions by her fiancee. Then in 1756, at a fair in Maybole, Agnes had her second romance. Meeting William Burnes, where Maybole Health Centre stands today, she fell in love and married Wiliam a year later in 1757. Over the years of their marriage, Agnes was to have seven children, but the eldest, as we know, was to become the most remarkable.

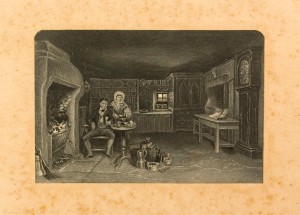

Settling down in the Alloway cottage, Agnes gave birth to Robert Burns two years into her marriage, in 1759. In his early years, Agnes is said to have had a huge influence on Burns through her love of singing Scottish songs, hymns and psalms, so much so that historian Robert Crawford said that ‘she was his first source and teacher of song.’ One song Robert Burns recalled her singing was the Highland Song: Leiger m’chose.

Leiger m’chose, my bonnie wee lass

An leiger m’ chose, my dearie

A’ the lee-lang winter night

Leiger m’ chose, my dearie.

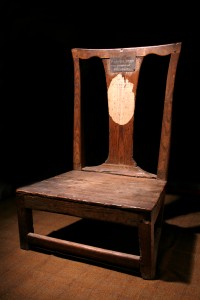

At the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum we celebrate Agnes by recreating the sounds of her singing in the cottage kitchen, and furnishing the house with items she would have used in her everyday life: milking stools, kirns, rolling pins, and spurtles, while her nursing chair is displayed in the museum. Sadly, not much history has survived of Agnes. Having received little education, she was unable to write letters, and thus what we know of her comes second hand, and passed down. Nonetheless, Agnes Burns must have been a strong woman. From taking care of a large family at the age of ten, to looking after her own large family as an adult, working a hard farming life, watching her husband die, living beyond the years of many of her own children, not to mention dealing with Robert’s many drama’s, Agnes Burnes was no doubt quite a woman.

So here’s to you Agnes Burnes: Happy Mothers Day!

Wardrobe Secrets: 6 Facts about 18th Century Female Fashion

Alexander Banks, Artist; John Miers, Artist

While many women in Robert Burns’s life came from the same poor and rural background as he did, one lady he fell in love with came from a much higher social strata. This lady was Agnes McLehose, (or Clarinda, as Burns called her). Agnes was part of the capital’s wealthy society and, through this; she met our bard in 1887. But what did the high class ladies of Burn’s lifetime look like? Here we have 6 unusual facts that lie behind 18th century female fashions!

1) No pants.

In the 18th century ladies might wear a long chemise, a corset, and then layers of petticoats, but no pants would feature in this ensemble of undergarments. Pants for women do not come in until the early 19th century, and even then they are split at the crotch, and tied at the waist: hence why we say ‘pair of pants.’

2) Mouse skin eyebrows.

Timorous beasties! It was fashionable for ladies to glue eyebrows made of mouse skin to their forehead. Why? This was largely due to make up practises at the time causing hair loss, which leads to fun fact number three:

3) Lead white paint

Ever wished to have that wonderful contrast between white skin and blushing cheeks? Well ladies would have achieved it by daubing white lead paint onto their faces, followed by red carmine (also containing lead). While this might have given you a temporary beautiful complexion, it would also have slowly poisoned you and perhaps led to hair loss.

4) Dimity Pockets

Pockets sewn into clothing arrive late in history. In the medieval period, people would string their bags and pouches from their belts. By this time in history, however, pockets for ladies were separate, and had ties attached so they could fasten them under their dress and around their waist.

5) Wigs

Powdered wigs became very fashionable in this period, for both men and women. Marie Antoinette would become very famous for her towering ‘pouffe’ (said at one point to have reached a height of 6ft!). For those who could afford these wigs, they had to be treated with care, while particularly huge wigs would involve sleeping upright with two or three pillows.

6) Teeth

Where’er that place be priests ca’ hell,

Where a’ the tones o’ misery yell,

An’ ranked plagues their numbers tell,

In dreadfu’ raw,

Thou, Toothache, surely bear’st the bell,

Amang them a’!

Address to a Toothache

Toothache was an unwanted visitor for rich and poor alike, with figures, such as George Washington, known for their fake teeth! So our ladies of the 18th century would probably hide behind a fan rather than flash their pearly whites. If you could afford it, you could buy Ivory dentures, but those often rotted quickly leaving a bad smell.

1860

W. H. Midwood

So behind the silks and embroidered dresses, it is clear that our 18th century ladies have a lot they keep hidden! As to whether Clarinda ever sported a ‘pouffe’ wig, or daubed on white paint for the perfect complexion, we will never really know. Sadly, aside from a silhouette, there are no contemporary paintings, or anything remaining from her wardrobe. Yet, by looking at the secrets on the 18th century wardrobe, we can create a picture of what Edinburgh ladies might have looked like in the time of Robert Burns.