Robert Burns Birthplace Museum

Toasts, Tatties and Traditions: The Truth Behind Burns Night

By Rhiannon Griffith, Visitor Services Assistant

Down a cobblestone street in the town of Dumfries, there sits a red sandstone house where, in 1796, Robert Burns took his final breath, aged just 37. After years of suffering from rheumatism, it was a consequent heart infection that led him to a premature death.

Yet his memory was to live on.

Winding the clock forward to five years later; on the 21st of July 1801, nine of Burns’ close friends and patrons gathered in his childhood home, Burns Cottage, in Alloway. The evening’s main purpose was to celebrate the poet’s timeless works and compelling life in a way that Burns himself would have loved: dinner, drinks, poetry and laughter aplenty.

The men enjoyed this night of revelry so much so that they decided to honour Burns again the following year, on what would have been the poet’s 43rd birthday. However, a misunderstanding of the exact date resulted in the men celebrating on the 29th of January. Third time lucky, in 1803, Burns’ life was finally commemorated on his birthday, the 25th of January – a date which would become cemented in Scottish history as ‘Burns Night’.

Over two centuries later, Burns Night has reached almost every corner of the earth. The proof is in this interactive Burns Supper map, compiled by the Centre for Robert Burns Studies and the University of Glasgow (2020), which is currently the most detailed record of global Burns Night activities ever made.

If that doesn’t have you convinced of his worldwide stature, Burns remains the only poet in the literary canon to have a day in the calendar devoted to celebrating his works. Certainly, one doesn’t need to have Scottish roots to feel tears prickle their eyes during a rousing rendition of Auld Lang Syne!

Burns Night has evolved from a modest meeting of Burns’ friends to a globalised – yet still strongly national – cultural event. And one that carries a great sense of pride for many Scots. Scotland is not only known for her fortitude, wild beauty and language. The Scots also invented the toaster, the TV and the telephone. We are often the butt of jokes and the victims of history. In these times of great uncertainty, Burns’ shrewd interpretation of humanity prevailing is a theme that has survived the sands of time. Whether right here in Alloway, or scattered across the globe, Burns Night brings us together, knitting us all into the tapestry of tradition. From the young to the old, the wealthy to the working, the lassies to the laddies, the left-wing to the right-wing – a Burns Night welcomes all and rejects none.

As the decades passed, more rituals were added to Burns Night traditions, such as musical performances of Burns’ songs, reciting the Selkirk Grace before guests dine, an injection of humour with a Toast to the Lassies, and an amusing retort in a Toast to the Laddies. At the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, we have on display original menus from early Burns Suppers, dating back nearly two centuries!

The main ingredient to a successful Burns Supper remains the same as it did some 220 years ago – the haggis. Served alongside its faithful friends, tatties (potatoes) and neeps (turnips), and washed down with a glass of whisky (or Irn Bru if you’re under 18!), the haggis is regarded as the centrepiece of the evening. And rightly so.

It is believed that haggis has been served up since the 15th century in Scotland. Originally an economical way to make the most of a sheep’s offal, it was popular among both the richest and poorest in society. It was not until Burns’ Address to a Haggis was published in 1786 that haggis finally earned its status as Scotland’s national dish (for those of you wondering – no, a haggis is not a furry, four-legged, mountain-dwelling, heather-munching creature!).

Never before has a poem about the superiority of blended sheep entrails and oatmeal been revered the world over as Address to a Haggis. Yet there is more to haggis than meets the eye (or tastebuds) and Burns pays homage to this through his subtle nod to Scottish patriotism in his poem. Through lines such as;

Auld Scotland wants nae skinkin ware

That jaups in luggies;

But, if ye wish her gratefu’ prayer,

Gie her a haggis! (45-48).

Burns recognises that haggis is far greater than the sum of its parts, and adds his own splash of colour onto the canvas of patriotism, all the while in tongue-in-cheek jest of more continental dishes.

This celebration of Scotland and her pulsing past is precisely the fuel which keeps the lamp of Burns and his Suppers burning today.

Little did those nine men know when they sat down to dine and toast the memory of their late friend, that 220 years later, not even a global pandemic can keep us from raising a glass to our bard. Though our Burns Suppers may be a little different this year, there has never been a better time to appreciate life’s simple pleasures – just as Burns did.

So, when you tuck into your haggis, neeps and tatties, or lift a wee dram to Burns this 25th of January, you might perhaps ponder what Rabbie would have made of our virtual Suppers! Above all else, this Burns Night, we give thanks to all that he has given us and all that he is yet to inspire.

This year the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum and the National Trust for Scotland are celebrating Burns Night virtually, please visit our Facebook page for more details!

https://www.facebook.com/NationalTrustforScotland

Sources:

The Burns Encyclopaedia. http://www.robertburns.org/.

McGinn, C. 2018. The Burns Supper: A Concise History.

Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. https://www.nts.org.uk/stories/the-first-burns-supper.

Visit Scotland. https://www.visitscotland.com/about/famous-scots/robert-burns/burns-night/.

Meet the Team: Yves Laird

During this time of isolation and social distancing we find ourselves in, relying on digital technology to communicate has never been more important, and we wanted to help curb any loneliness and boredom by branching out with a new series of blogs about our staff. Our team were presented with ten questions to answer to help you to get to know them better. Next time you visit our Museum in Alloway, perhaps you’ll remember the name and the face of one of our staff members, helping you feel more connected #ForTheLoveOfScotland.

So without further ado, let us introduce to you…

1. Name

- Yves Laird

2. How long have you worked at RBBM?

- 11 Months

3. What is your position at RBBM?

- Visitor Services Assistant (Catering)

4. What is your favourite thing about working (or best memory) at RBBM?

- I love being able to work among a great team of people in the heart of Alloway to provide our local community and worldwide visitors with service fit for a bard!

5. What is your favourite fact, song and/or poem by Robert Burns?

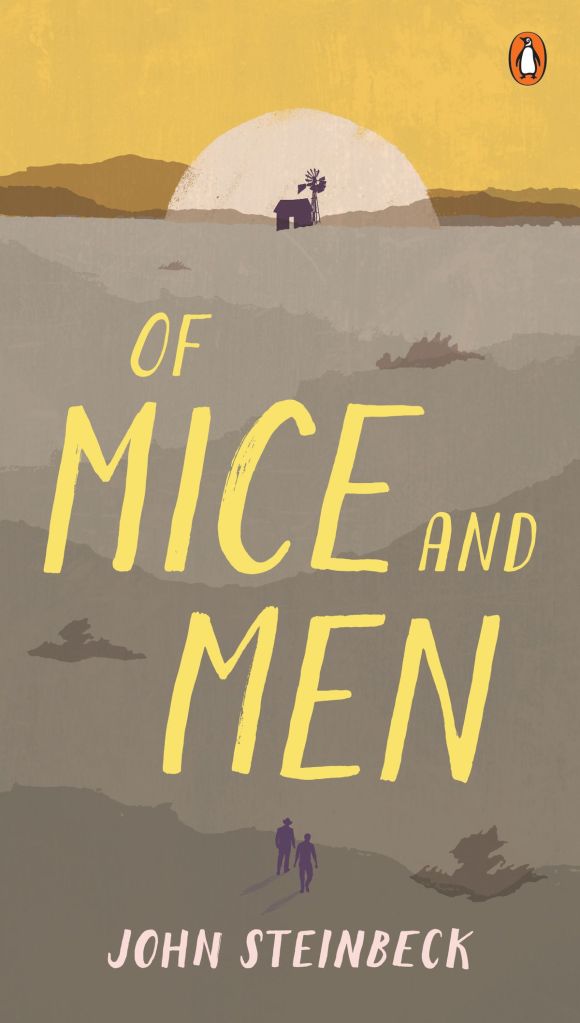

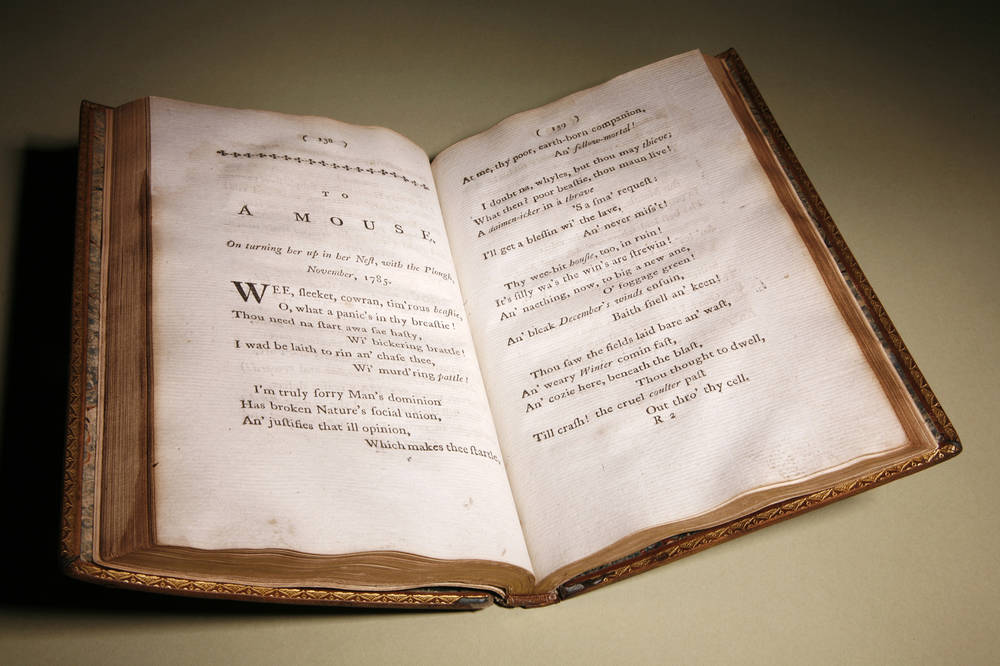

- As an English Literature student, not only do I appreciate Burns’s own work, but the works he provided inspiration for. His poetry is said to have inspired John Steinbeck’s 1937 novel ‘Of Mice and Men’, specifically by a line in the poem ‘To a Mouse’.

6. What is your favourite Scots word?

- Wheesht! Meaning be quiet as in “haud yer wheesht!”

7. Do you have any special skills/hobbies/talents? (Doesn’t need to be work related, let’s see your hidden talents!)

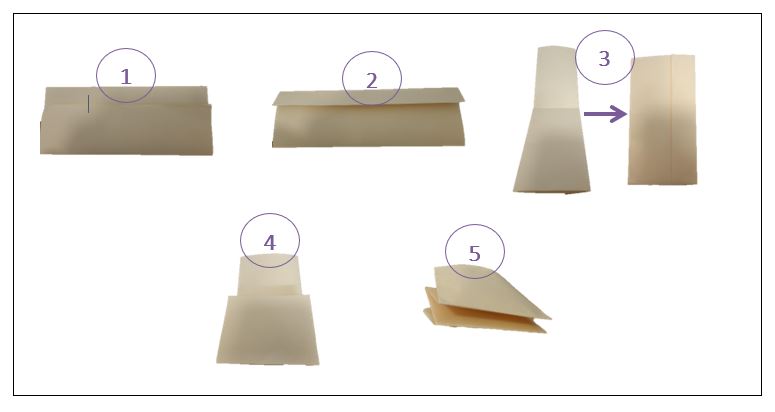

- I’m close to having an architectural degree, as seen in my Tunnocks teacake towers!

8. What is your dream vision/project?

- I would love to work in the emergency services! On a less realistic note, have my yet- to- be written novels published in the literary canon.

9. Who is your idol and why? (can be famous, could be your granny….up to you!)

- Prince! As a creative genius who wasn’t afraid to push boundaries, his commitment to his work and art form shines through his great works. The fact he wasn’t afraid to stand out from the crowd and was able to walk away from those who held him back is truly inspirational.

10. Where is your favourite place in the world and why?

- While the rain pours down 361 days of the year here, I’m proud to say home is Scotland. Nowhere can beat it with its rugged scenery, tranquil lochs and (mostly) friendly people!

Meet the Team: Chris Waddell

During this time of isolation and social distancing we find ourselves in, relying on digital technology to communicate has never been more important, and we wanted to help curb any loneliness and boredom by branching out with a new series of blogs about our staff. Our team were presented with ten questions to answer to help you to get to know them better. Next time you visit our Museum in Alloway, perhaps you’ll remember the name and the face of one of our staff members, helping you feel more connected #ForTheLoveOfScotland.

So without further ado, let us introduce to you…

1. Name

- Christopher Waddell

2. How long have you worked at RBBM?

- Seven Years

3. What is your position at RBBM?

- Downtrodden and defeated. Oh you mean work wise?! I am the Learning Manager.

4. What is your favourite thing about working (or best memory) at RBBM?

- I really enjoy when we get a great class of kids who engage with the site and subject matter. They make me laugh and inspire me sometimes with their outlook and knowledge of the world. I enjoy working alongside the team too, despite my continual joking and rude comments I really am very fond of them. Mostly.

5. What is your favourite fact, song and/or poem by Robert Burns?

- Fact – Burns was familiar with literary heavyweights – such as Alexander Pope – when he was in his mid-teens, and drawing inspiration, was able to compose pieces such as ‘Now Westlin Winds’ at such an early age. This qualifies for me the notion that he was a genius.

- Song – The Lea Rig

- Poem – a bit obvious but probably ‘Tam O’ Shanter’.

6. What is your favourite Scots word?

- Gowdspink, but a’hm no tellin ye whit it means, ye’ve tae awa an fun oot fur yersel!

7. Do you have any special skills/hobbies/talents?

- I can identify most plants and beasts you’ll see on a walk through the Scottish countryside and then tell a whole raft of dull facts to anyone who will listen.

- I can play the moothie and recite the script from ‘Goodfellas’(not at the same time).

8. What is your dream vision/project?

- To completely immerse myself in a rural idyll.

9. Who is your idol and why? (can be famous, could be your granny….up to you!)

- Loads of people, but in reality my late father who was great inspiration to me and a good friend and I miss him very much, and, a bit soppy here, my lovely wife because she puts up with me with amazing good humour and endless tolerance.

10. Where is your favourite place in the world and why?

- Difficult to choose between Sicily or Arran, both places I have been very happy and always in the company of my wife.

Meet the Team: Lauren McKenzie

During this time of isolation and social distancing we find ourselves in, relying on digital technology to communicate has never been more important, and we wanted to help curb any loneliness and boredom by branching out with a new series of blogs about our staff. Our team were presented with ten questions to answer to help you to get to know them better. Next time you visit our Museum in Alloway, perhaps you’ll remember the name and the face of one of our staff members, helping you feel more connected to our property.

So without further ado, let us introduce to you…

1. Name

- Lauren McKenzie

2. How long have you worked at RBBM?

- 6 months (Started in September 2019)

3. What is your position at RBBM?

- Events Manager

4. What is your favourite thing about working (or best memory) at RBBM?

- My favourite memory so far has been delivering the Burns programme in January. The team put in an immense effort to pull together all of the elements for the weekend and it was a very proud moment for me to see the success of this. I, of course, have to mention the incredible team of staff and volunteers that work at RBBM that make everything so enjoyable and easy!!

5. What is your favourite fact, song and/or poem by Robert Burns?

- My favourite Burns song is ‘My Love Is Like A Red, Red Rose’.

6. What is your favourite Scots word?

- It has to be ‘braw’. Braw means beautiful, pretty, attractive… you could call a lassie braw or you could say “it’s a braw day the day”.

7. Do you have any special skills/hobbies/talents?

- I have played in a brass band for over 12 years and somehow manage to find the time to compete on regional and national levels in between events at the museum!

8. What is your dream vision/project?

- My dream is to visit every continent in the world – only South America and Australia to go!!

9. Who is your idol and why?

- I am going to cheat a wee bit and have two – both my grannies! Although, I am biased, they are just the BEST in the world and have taught me everything I know.

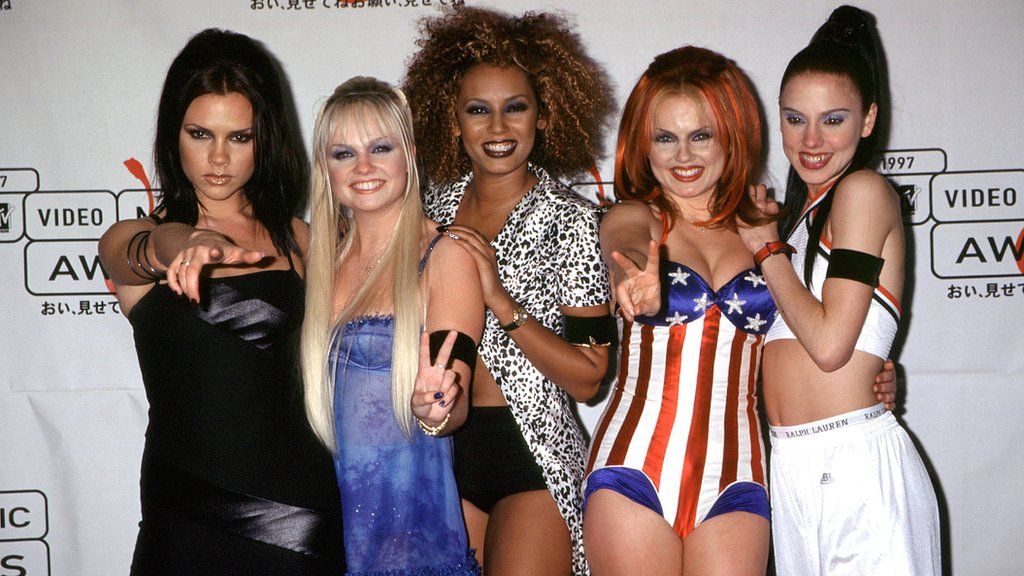

- If it was to be someone famous, it has to be the Spice Girls (again, cheating because there is five of them!) I have loved them since a really young age – GIRL POWER!

10. Where is your favourite place in the world and why?

- I have travelled to a few places but there is nothing quite like being home in Ayrshire – it’s fair braw.

Fragments

Two memorialising students from the University of Glasgow Scottish Literature department visited the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum recently to do research and blog-writing as part of their course. The following blog was researched and written by Struan McCorrisken.

Two objects in particular represent a curious facet of the cult of Burns, that is the accumulation and preservation of any and all tangible aspects of the Bards’ life. A fragment, no more than the size of a matchbox, of Jean Armour and Robert Burns’ marital bed, is encased in a large wooden discus and visible beneath a glass plate. The other is a small board containing two strips of material roughly large enough to make a small sock out of. The black silk is merely silk; and the piece of wood, just wood. What truly matters is the association these objects possess; an aspect so powerful it has driven them to be curated and displayed despite being only tiny fragments of the original whole.

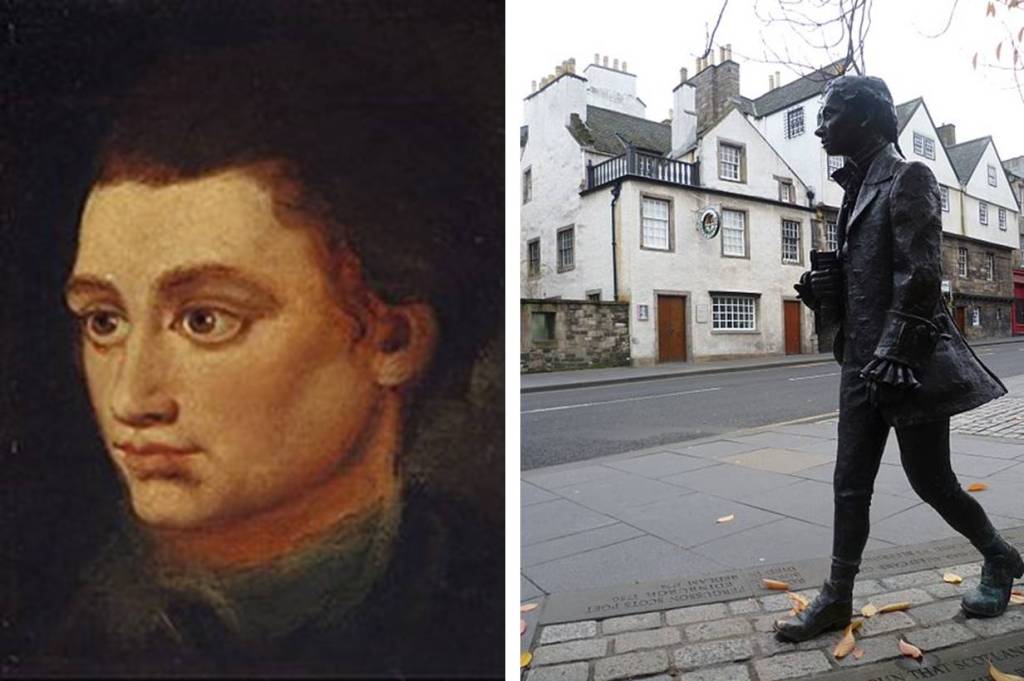

This sort of collecting exemplifies precisely why these objects are valuable. Not the objects themselves, but the connection to the past they offer, the prospect of tangibility that they represent. The type of collecting and commemoration that Burns undergoes is similar almost to that of a medieval saint. This sort of fervent reverence began very soon after Burns’ death, and we may well consider it a sign that Calvinist Scotland, devoid of pomp and pageantry through the stifling presence of the Kirk and the absence of the king, was looking for something to fill the gap. This perhaps was a search for joyful veneration of a figure beyond the austere auspices of the Kirk. Burns’ own rebellious stance against much of the Kirk’s posturing may have added to that attraction. While the comparison of Burns to a saint may sound fanciful, but it’s worth considering how saints are venerated. They are commemorated with talismans, awards and honours are given in their names, statues are erected at places they had a connection to, and they have specific symbols and icons associated with them. Some have specific days they are venerated on, or specific shrines dedicated to them. We certainly manufacture talismans of Burns, as any glance around a Scottish gift shop reveals. There are awards in his name, such as the Robert Burns Humanitarian Award, and a multitude of organisations associated with him. Scotland is replete with statues and plaques of Burns, miniature shrines almost, at places associated with his life and the lives of those associated with him. Images such as the mouse, the plough and the rose are associated with Burns, arguably his very own attributes. He certainly has his own day, and the proposed desire for ritual in the Scots certainly comes to the fore here, reinforced heartily by Walter Scott’s own contributions to images of Scottish culture (tartan, kilts etc). We eat food associated with Burns and toast his “immortal memory”. Items from his life, however fragmentary, are collected and displayed in museums. A new form of reliquary perhaps?

Indeed, it may be postulated that Burns is a new form of saint for a modern, more secular, Scotland. A person of great achievement whom we admire, commemorate, and attempt to emulate. A part of this commemoration is undoubtedly the use of objects, in any condition, to help us connect with the man, long since passed.

Celebrating Scots Language

As today is International Mother Language Day, our blog post explores the history of Scots language to celebrate and promote Scottish linguistic heritage.

Scots is descended from a form of Anglo-Saxon brought to the south-east of present day Scotland by the Angles (Germanic-speaking peoples) around AD 600. The video below, from The University of Edinburgh, illustrates the origins of Scots language.

Like many European countries, early Scots speakers primarily used Latin for official and literary purposes. The earliest surviving written poem in Scots, dated to 1300, is a short lyric on the death of King Alexander III (ruled 1249-1286) which appeared in Andrew Wyntoun’s work entitled The Original Chronicle:

“Qwhen Alexander our kynge was dede, That Scotland lede in lauch and le, Away was sons of alle and brede, Off wyne and wax, of gamyn and gle. Our golde was changit into lede. Crist, borne into virgynyte, Succoure Scotland and ramede, That is stade in perplexitie”.

Yet, the first Scots poem of any length called The Brus by John Barbour was recorded in 1375. Composed under the patronage of Robert II, this poem’s tale follows the actions of Robert the Bruce through the first war of independence.

The History of Scots from the 14th– 18th Century

Between the 14th and 16th century, writing in the vernacular thrived during the reigns of James III (ruled 1460-1488) and James IV (ruled 1488-1513): Scots language truly came into its own. This period’s Scots poets are known as medieval makars or master poets, after William Dunbar’s the Lament for the Makaris, for the great literacy culture that was produced in lowland Scotland. Dunbar was a virtuosic poet with an impressive range, varying from elaborate religious hymns to scurrilous bawdy verse.

Also a makar, King James VI (ruled 1567-1625) laid down a standard writers were expected to follow in his essay on literary theory entitled The Reulis and Cautellis. However, after James VI also became James I of England in 1603, Scots language and makars were no longer supported by the Royal Court. Pre-1603, James VI voiced the differences between English and Scots but now, as ruler of the British Empire, he attempted to Anglicise Scottish society for cultural, linguistic and political union of his kingdoms. Herein, the literary activity of 17th century Scots poets declined as many, like William Drummond of Hawthornden, decided to write in English instead. This change of language was encouraged by the Royal Court alongside the larger and more lucrative English publishing markets. In Scotland, all classes continued to write and speak in Scots but, for publications writers had their texts ‘Englished’.

The Great Scots Poets of the 18th Century

In the 18th century, under the 1707 Treaty of Union, Scotland joined England to form the new state of Great Britain and poets began to utilise an increasingly bilingual literary situation. Poets combined Augustan English poetry with Scots songs, tales and older poems to create a vernacular revival in Scots verse. The work of poets such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns demonstrated the popularity and poetic nature of Scots as a literature. These poets, expressing a national identity, produced poems that were, and continue to be, widely read.

Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) was born in Lanarkshire and educated at Crawfordmoor Parish School. Following his mother’s death, Ramsay moved to Edinburgh to study wig-making and eventually opened a shop near Grassmarket. He was an eminent portrait painter and began writing poetry from the early 1700s. In 1721, Ramsay published his first volume as a blend of English language and Scots poems. He abandoned the wig-making trade to become a bookseller, opening a shop near Edinburgh’s Luckenbooths- this also became Britain’s first circulating library. Ramsay’s works, such as Tea-Table Miscellany (1724), The Ever Green (1724) and The Gentle Shepard (1725), laid the foundations for Scot writers like Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns.

Robert Fergusson (1750-1774) was born in Edinburgh’s Old Town to Aberdeenshire parents. He attended St. Andrews University and became infamous for his pranks- for which he came close to expulsion. In 1771, Fergusson anonymously published his first trio of pastorals entitled Morning, Noon and Night. He amassed an exquisite range of about 100 poems, developing existing literary forms and contributing to contemporary debate. Aged 24, Fergusson experienced a fatal blow to his head falling down a flight of stairs, he was deemed ‘insensible’ and transferred to Edinburgh’s Bedlam madhouse where he later died. In 1787, Robert Burns erected a monument at his grave, commemorating Fergusson as ‘Scotia’s Poet’.

Robert Burns called Fergusson “my elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in muse”. Clearly inspired by the poet, Burns adopted both Fergusson and Ramsay’s use of Scots words and verse to master his own poetry and advance Scots literature. In doing this, Burns became Scots language’s most recognised voice with poems and songs read and sung worldwide. The Robert Burns Birthplace Museum displays volumes and poems by Fergusson and Ramsay (below), highlighting the similarities to Burns’ work in terms of tone, format, subject matter and, of course, Scots language.

The History of Scots Post-Burns to the Present

In the 19th century, building on the work of Scots poets, novelist began combining English and Scots in their writings. More often, English was used for the main narrative and Scots voiced Scots-speaking characters or short stories.

After this period, the 20th century saw a radical renaissance of Scots poetry, primarily through Hugh MacDiarmid (pen name of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid’s work The Scottish Chapbook, reassessed early Scots verse by using words from across different regions. Later, Edinburgh poet Robert Garioch reopened links to the Scots verse MacDiarmid devalued. Garioch, to a greater extent than MacDiarmid, developed a form of Scots united to any particular locality and produced a model that future writers could follow. Other 20th century poets, included Edwin Morgan, and his translation of Vladmir Mayakovsky’s poetry into Scots, as well as Tom Leonard’s Six Glasgow Poems.

Today, Scots language continues to thrive. In communities across Scotland, people use Scots as a language to write and speak. As the 2011 Scottish Census reported, there are 1.5 million speakers of Scots within Scotland, which is around 30% of the population.

So, why not challenge yourself? And join them? To celebrate Scots language and International Mother Language Day, learn a new word or a new phrase or more!

Check out the links below for more ways to learn Scots:

- On social media, we run a Scots word of the week campaign, encouraging our followers to guess and discuss what they mean. We often get international audiences commenting on the similarities between Scots and various European languages. Check it out on Facebook (@RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum) and Twitter (@RobertBurnsNTS).

- Search our blog for Scots language posts: https://burnsmuseum.wordpress.com/tag/scots-language/

- For Scots on Twitter, take a look at these pages: @lairnscots, @scotslanguage, @ScotsScriever, @tracyanneharvey @rabwilson1 and @TheScotsCafe.

- Join the Open University’s FREE online Scots language and culture course: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705

- Or, check out some of these websites: https://www.scotslanguage.com/

https://www.gov.scot/policies/languages/scots/

http://www.cs.stir.ac.uk/~kjt/general/scots.html

https://education.gov.scot/improvement/Documents/ScotsLanguageinCfEAug17.pdf

Gang oan, gie it an ettle!

The First Burns Supper and Beyond!

With Burns Night approaching, let’s delve in to the origins of the very first Burns Supper in Alloway, and how this grew into the global Burns Suppers held today!

The first Burns Supper was held in July 1801 at the Burns Cottage in Alloway, five years after Burns’ death. Led by Freemason Reverend Hamilton Paul, it was an informal affair between a small gathering of his fellow freemasons. Burns was also part of the Freemasons at Tarbolton, which allowed him to form a large network of friends and acquaintances, and the nine men present at the first Burns Supper were closely connected with him. This first supper was a toast to Burns’ life, and the men recited his most lively works to symbolise his exciting and accomplished legacy as a bard. They considered the first supper a huge success, and arranged to hold a second Burns Supper for his birthday in January. From this the tradition of the Burns Supper began.

At this time Clubs, where (usually) men met regularly to eat, drink and socialise, were well established, and so the format of the Burns Supper lent itself well to this popular style of social gathering in Scotland. At the first Burns Supper ‘To a Haggis’ was read before the haggis was eaten and several rounds of toasts were given; these key rituals have remained the integral components of Burns Suppers throughout the years. Hamilton Paul’s interpretation of these most important elements of Burns’ work and life allowed for the supper format to be easily adapted to other sites out-with the Burns Cottage.

According to writer Clark McGinn the Burns Supper evolved through two phases; the charismatic period and the traditional period. The charismatic period began from the first Burns Supper, and includes the more informal suppers between those directly connected to Burns, or Ayrshire. These were taken on by members of literary clubs in particular.

In Burns’ Day, the literary scene was close-knit and active in meeting at clubs and other occasions. This must have greatly accelerated the popularity of Burns Suppers as these passionate literary fans and writers were proactive in gathering regularly, spreading the idea across Scotland. Spontaneous Burns Suppers began to be held across Ayrshire, and eventually in other parts of Scotland.

Although informal to begin with, they gradually became more regulated and standardised, with stricter rules regarding the format as those outside of Burns’ circles and even Ayrshire circles became involved. The first Burns Supper held in Edinburgh in 1815 was alike to the informal suppers held in clubs across Ayrshire, however the supper for the following year was presented as a formal public dinner, to be held every three years. Attended by Sir Walter Scott, the 1816 Burns Supper pledged to give Robert Burns the honorary tribute he deserved, and so magnificence and splendour were at the forefront of the event. This marked the transition into the traditional period of the Burns Supper format.

What had started out as a Burns Supper had grown into bigger and grander events, which helped Burns’ popularity all over the country intensify. Burns Suppers held in London in the early 1800s introduced the idea to a wider audience, and they were also appearing in India, Australia and America. The traditional period continued throughout the Victorian era, which saw the Burns Festival Procession of 1844 in Alloway and the Burns Federation established in 1885. The Burns Federation sought to unite all of the Burns Clubs across the world, and still exists today as a common link for Burns fans globally.

Today Burns Supper celebrations continue all over the world, from the Cottage where the first Supper was held, all the way to Canada and New Zealand. The toast to the haggis is still a key feature of the Burns Supper, and all of the traditions of the first Supper have remained important throughout the years. For Burns Night 2020 we have lots of exciting events on the 25th and 26th of January at the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, we hope to see you there!

By Kirsty Reid, Learning Trainee

Further Reading: ‘The Burns Supper: A Comprehensive History’, by Clark McGinn

Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot?

Sung at Hogmanay (Scots for New Years Eve) the world over, ‘Auld Lang Syne’ is arguably the most recognisable and the most performed of all Robert Burns’s songs, but how much do you actually know about this iconic song?

The song we are so familiar with is actually a reworking of earlier Scottish songs, and therefore exemplifies the process by which Burns collected and reworked pre-existing material. Burns read either one or both of Robert Aytoun’s (b.1570 but published in 1711 in volume 3 of Watson’s Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems) and Allan Ramsay’s (published 1720) texts which have similar lines like “on old long syne” and “as they did lang syne”. These texts differ in theme; Aytoun’s is about lovers and then Ramsay’s is about love, war and comrades. Burns is inspired by these but he retains very little from earlier versions save the famous opening line ‘Should auld acquaintance be forgot’; he adapts the lyric to make it a more universal song, suitable to the late eighteenth-century, with a theme of friendship. Moreover, the tune with which we are familiar was not the only one available…

In Burns’s ‘Auld Lang Syne’, note the familiar ‘objects in nature’ he mentions like “braes” or hillsides covered in “gowans” or daisies/buttercups and “burns” or streams in which one might paddle. Burns was very inspired by nature and this is reflected in all his works including ‘Auld Lang Syne’!

Robert Burns sent his first draft of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ to a very important woman before it was even published! Frances Dunlop was a wealthy heiress almost thirty years older than Burns and they became friends because she contacted Burns after reading his ‘Kilmarnock Edition’ book of poetry. She enjoyed it so much, it roused her out of a long period of depression and she wrote to Burns for more copies, which resulted in a long friendship which lasted till Burns’s death. The Bard sought advice and guidance from Frances, who was a maternal figure in his life, and he clearly valued her opinion.

collection at Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, in Alloway, Scotland.

This handwritten copy of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ ISN’T an original by Robert Burns – although it has convinced some in the past…

Scotland’s collection at Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, in Alloway, Scotland.

It is in fact a forgery by the prolific Alexander Howland Smith – also known as ‘Antique Smith’. Smith was an Edinburgh law clerk who produced a large quantity of forgeries during the 1880s and early 1890s. He forged documents from a number of high profile figures, including Burns, Mary Queen of Scots, James VI, Oliver Cromwell, William Wordsworth, Walter Scott and many others! He was exposed in 1892, when an Edinburgh newspaper published one of his forgeries and an acquaintance recognised his handwriting. Smith was brought to trial in 1893 (not for forgery, but instead for selling forgeries) and was sentenced to 12 months imprisonment.

Did you know that in 2009 a special edition ‘Auld Lang Syne’ £2 coin was released? The special edition celebrated the 250th anniversary of Robert Burns’s birth (25 January 1759). Although not the rarest of the £2 coins, it’s not very common either. Next time you get your change, have a wee look for it!

Burns’s famous song has made it into popular culture too! Remember Harry declaring his love for Sally to the sound of Burns in When Harry Met Sally (1989)? Did you catch Bob’s serenade to a rat in Minions (2015)?

You can also hear the song in the Sex and the City Movie (2008), Elf (2003) – as well as in the classic films The Gold Rush (1925), Wee Willie Winkie (1937) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

Most recently, did anyone notice in Netflix’s TV programme The Crown, season 3 (2019), episode 5 entitled “Coup”, a large group singing it to say farewell to Lord Mountbatten as he retired from a long-standing post?

Furthermore, countless recording artists have also covered the song throughout this time, including performers as diverse as Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, B.B. King, The Beach Boys, Jimi Hendrix, John Travolta and Olivia Newton John, Rod Stewart, and Mariah Carey, to name only a few. Such widespread interest in the song has largely been driven by its association with the festive period.

Listen to a cover of the version here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qqtkDU72yrg

It has connections with countries across globe – and not just countries historically where a lot of Scottish people emigrated. Two countries have used the tune most commonly associated with ‘Auld Lang Syne’ for their national anthem: the Maldives and, from 1901 until the middle of the last century, Korea. A version of the tune with new lyrics related to graduation, ‘Hotaru no Kikari’, has been sung in Japan since the late nineteenth century and is used also in some Japanese stores to signal closing-time.

The song is connected to war history as well! It was frequently played by regimental bands of the Union army in the time of the American Civil War during the 1860s. Apparently, with its associations of parting and absence from home, its tugging on the heartstrings was thought to be bad for morale and it was consequently banned. However, on accepting the surrender terms of the Confederacy in 1865, General Ulysses S. Grant of the victorious union side apparently ordered the tune to be played as a concession to his troops.

Again in the theatre of war, during the famous World War I Christmas truce of 1914, British and German soldiers joined together to sing the song (among several others). A poignant reminder of the power of the song; to imagine it drifting across ‘no man’s land’ is tragic indeed.

So, why is it so famous nowadays anyway? Well, Burns’s song was transmitted across the generations and is now claimed by communities far broader than expatriate Scots around the world, because a Canadian dance band, the Guy Lombardo Band, became a feature of New York’s 1st January celebrations from 1929 at the Roosevelt Hotel in the city. Over the next thirty years the band’s choice of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ as a signature part of their Hogmanay performance made the song a world-wide phenomenon, and a recording of the Lombardo version is still heard today in Times Square, New York, as the New Year is brought in.

Final fun fact to conclude: ‘Auld Lang Syne’ is the most frequently performed song after ‘Happy Birthday’. We hope you listen to, sing and join hands to one of Burns’s most precious gifts to the world this Hogmanay.

Bards, Burns an Blether in The Bachelors’

It’s owre twa hunner year syne The Bachelors’ Club in Tarbolton saw the young Robert Burns an his cronies speirin aboot the issues o thaur day. It is therefore a braw honour tae gie this historic biggin a heize ainst mair by bein involved in organisin and hostin monthly spoken word an music nichts in the place whaur Robert Burns fordered his poetic genius, charisma an flair fir debate.

The Bachelors’ Club nichts stairtit in March this year eftir Robert Burns Birthplace Museum volunteer Hugh Farrell envisaged the success of sic nichts in sic an inspirational setting.

Tuesday the third o September saw the eighth session, an it wis wan we will aye hae mind o. Wullie Dick wis oor compère as folk favoured the company wi a turn.

Oor headliner wis Ciaran McGhee, singer, bard an musician. Ciaran bides an works in Embra an I first shook his haun some twa year syne at New Cumnock Burns Club’s annual Scots verse nicht. The company wis impressed then an agin at the annual “smoker” an at a forder Scots verse nicht. Ciaran traivelled doon tae Ayrshire tae play fir us, despite haen jist duin a 52 show marathon owre the duration o Embra festival.

Ciaran stertit wi a roarin rendition o “A Man’s a Man for a That”, an we hud a blether aboot hoo this song is as relevant noo, in these days o inequality an political carnage, as it wis twa hunner year syne, a fine example o Burns genius an insicht. Ciaran follaed wi Hamish Imlach’s birsie “Black is the Colour”, the raw emotion gien us aa goosebumps!! Ciaran also performed Johnny Cash’s cantie “Folsom Prison Blues”, an then Richard Thomson’s classic “Beeswing”, a version sae bonnie it left us hert-sair! Ciaran also performed tracks fae his album “Don’t give up the Day Job”.

The company wir then entertained by Burns recitals an poetry readins fae a wheen o bards an raconteurs. A big hertie chiel recited “The Holy Fair”, speirin wi the company on hoo excitin this maun hae buin in Burns day, amaist lik today’s “T in the Park”.

We hud “Tam the Bunnet” a hilarious parody o Tam o Shanter an Hugh Farrell telt us aboot the dochters ca’ad Elizabeth born tae Burns by different mithers, Burn’s first born bein “Dear bocht Bess”, her mither servant lass Bess Paton. Later oan cam Elizabeth Park, Anna Park’s dochter, reart by Jean Armour, an thaur wis wee Elizabeth Riddell, Robert an Jean’s youngest dochter wha deid aged jist 3 year auld. A “Farrell factoid” we learned wis that in Burns day, if a wee lassie wis born within mairrage, she was ca’ad fir her grandmither, if she wis born oot o wedlock she taen her mither’s first name. Hugh recited “A Poet’s Welcome To His Love-Begotten Daughter” fir us, the tender poem Burns scrievit, lamentin his love fir his first born wean, Elizabeth Paton.

We hud spoken word by various bards on sic diverse topics as a hen doo, a sardonic account o an ex girlfriend’s political tendencies, an a couthie poem inspired by a portrait o a mystery wummin sketched by the poets faither. In homage tae Burn’s “Poor Mailie’s Elegy”, we hud a lament in rhyme scrievit in the Scots leid, featurin the poet’s pet hen.

We learned o the poetess Janet Little, born in the same year as Burns, who selt owre fowre hunner copies o the book o her poetry she scrievit. This wummin wis kent as “The Scotch Milkmaid” an wis connected tae Burn’s freen an patron, Mrs Frances Anna Dunlop.

We also learned o hoo Burns wis spurned by Wilhelmina Alexander, “The Bonnie Lass of Ballochmyle” an hoo, eftir her daith, she wis foun tae hae kept a copy o the poem Burns scrievit fir her.

We hud mair hertie music fae Burness, performin Burns an Scottish songs sic as “Ye Jacobites by Name” an a contemporary version o “Auld Lang Syne” wi words added by Eddie Reader tae an auld Hebrew tune.

We hud “Caledonia” an “Ca the Yowes tae the Knowes” sung beautifully by a sonsie Auchinleck lass wha recently performed it at Lapraik festival in Muirkirk (oan Tibby’s Brig nae less!).

The newly appointed female president o Prestwick Burns Club entertained us on her ukelele wi the Burns song “The Gairdner wi his Paiddle” itherwise kent as “When Rosie May Comes in with Flowers”.

At the hinneren wi hud a sing alang tae Seamus Kennedy’s “The Little Fly” on the guitar an Ciaran feenished wi “Ae Fond Kiss”, interrupted by his mammy wha phoned tae see when he wis comin haim tae New Cumnock!

We hud sae muckle talent in The Bachelors’, that we didnae hae time fir a’body to dae a turn, so thaim that didnae will be first up neist time.

A hertie thanks tae a the crooners, bards an raconteurs an tae a’body in the audience fir gien up thaur time, sharin thaur talent an ken an gien sillar tae The Bachelors’ fund. Sae faur we hae roused £862 which hus been paid intae the account fir the keepin o The Bachelors’ Club.

Hugh Farrell is repeatin history by stertin a debatin group in The Bachelors’ on Monday 11th November, 239 year tae the day syne Burns launched it first time roon. Thaur will be a wee chainge tae the rules hooever, ye dinnae hae tae be a Bachelor an ye dinnae need tae be a man tae tak pairt!!

The Bachelors’ sessions are oan the 1st Tuesday o every month 7pm tae 10.30pm an a’body wi an enthusiasm for Burns is welcome.

Scrievit by Tracy Harvey, Resident Scots Scriever fir RBBM