museum

Meet the Team: Yves Laird

During this time of isolation and social distancing we find ourselves in, relying on digital technology to communicate has never been more important, and we wanted to help curb any loneliness and boredom by branching out with a new series of blogs about our staff. Our team were presented with ten questions to answer to help you to get to know them better. Next time you visit our Museum in Alloway, perhaps you’ll remember the name and the face of one of our staff members, helping you feel more connected #ForTheLoveOfScotland.

So without further ado, let us introduce to you…

1. Name

- Yves Laird

2. How long have you worked at RBBM?

- 11 Months

3. What is your position at RBBM?

- Visitor Services Assistant (Catering)

4. What is your favourite thing about working (or best memory) at RBBM?

- I love being able to work among a great team of people in the heart of Alloway to provide our local community and worldwide visitors with service fit for a bard!

5. What is your favourite fact, song and/or poem by Robert Burns?

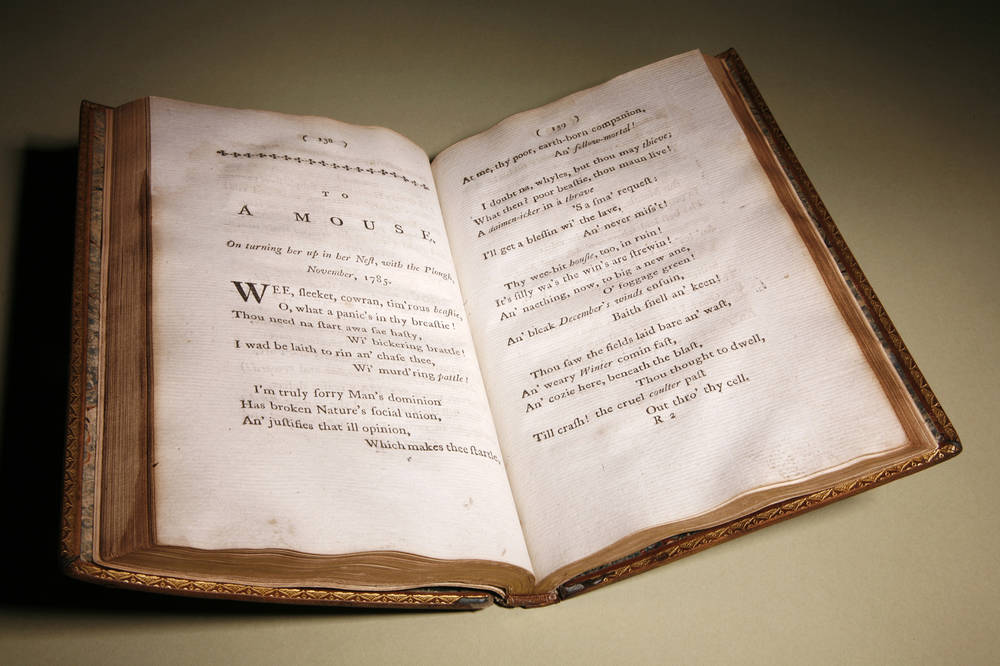

- As an English Literature student, not only do I appreciate Burns’s own work, but the works he provided inspiration for. His poetry is said to have inspired John Steinbeck’s 1937 novel ‘Of Mice and Men’, specifically by a line in the poem ‘To a Mouse’.

6. What is your favourite Scots word?

- Wheesht! Meaning be quiet as in “haud yer wheesht!”

7. Do you have any special skills/hobbies/talents? (Doesn’t need to be work related, let’s see your hidden talents!)

- I’m close to having an architectural degree, as seen in my Tunnocks teacake towers!

8. What is your dream vision/project?

- I would love to work in the emergency services! On a less realistic note, have my yet- to- be written novels published in the literary canon.

9. Who is your idol and why? (can be famous, could be your granny….up to you!)

- Prince! As a creative genius who wasn’t afraid to push boundaries, his commitment to his work and art form shines through his great works. The fact he wasn’t afraid to stand out from the crowd and was able to walk away from those who held him back is truly inspirational.

10. Where is your favourite place in the world and why?

- While the rain pours down 361 days of the year here, I’m proud to say home is Scotland. Nowhere can beat it with its rugged scenery, tranquil lochs and (mostly) friendly people!

Meet the Team: Chris Waddell

During this time of isolation and social distancing we find ourselves in, relying on digital technology to communicate has never been more important, and we wanted to help curb any loneliness and boredom by branching out with a new series of blogs about our staff. Our team were presented with ten questions to answer to help you to get to know them better. Next time you visit our Museum in Alloway, perhaps you’ll remember the name and the face of one of our staff members, helping you feel more connected #ForTheLoveOfScotland.

So without further ado, let us introduce to you…

1. Name

- Christopher Waddell

2. How long have you worked at RBBM?

- Seven Years

3. What is your position at RBBM?

- Downtrodden and defeated. Oh you mean work wise?! I am the Learning Manager.

4. What is your favourite thing about working (or best memory) at RBBM?

- I really enjoy when we get a great class of kids who engage with the site and subject matter. They make me laugh and inspire me sometimes with their outlook and knowledge of the world. I enjoy working alongside the team too, despite my continual joking and rude comments I really am very fond of them. Mostly.

5. What is your favourite fact, song and/or poem by Robert Burns?

- Fact – Burns was familiar with literary heavyweights – such as Alexander Pope – when he was in his mid-teens, and drawing inspiration, was able to compose pieces such as ‘Now Westlin Winds’ at such an early age. This qualifies for me the notion that he was a genius.

- Song – The Lea Rig

- Poem – a bit obvious but probably ‘Tam O’ Shanter’.

6. What is your favourite Scots word?

- Gowdspink, but a’hm no tellin ye whit it means, ye’ve tae awa an fun oot fur yersel!

7. Do you have any special skills/hobbies/talents?

- I can identify most plants and beasts you’ll see on a walk through the Scottish countryside and then tell a whole raft of dull facts to anyone who will listen.

- I can play the moothie and recite the script from ‘Goodfellas’(not at the same time).

8. What is your dream vision/project?

- To completely immerse myself in a rural idyll.

9. Who is your idol and why? (can be famous, could be your granny….up to you!)

- Loads of people, but in reality my late father who was great inspiration to me and a good friend and I miss him very much, and, a bit soppy here, my lovely wife because she puts up with me with amazing good humour and endless tolerance.

10. Where is your favourite place in the world and why?

- Difficult to choose between Sicily or Arran, both places I have been very happy and always in the company of my wife.

Meet the Team: Lauren McKenzie

During this time of isolation and social distancing we find ourselves in, relying on digital technology to communicate has never been more important, and we wanted to help curb any loneliness and boredom by branching out with a new series of blogs about our staff. Our team were presented with ten questions to answer to help you to get to know them better. Next time you visit our Museum in Alloway, perhaps you’ll remember the name and the face of one of our staff members, helping you feel more connected to our property.

So without further ado, let us introduce to you…

1. Name

- Lauren McKenzie

2. How long have you worked at RBBM?

- 6 months (Started in September 2019)

3. What is your position at RBBM?

- Events Manager

4. What is your favourite thing about working (or best memory) at RBBM?

- My favourite memory so far has been delivering the Burns programme in January. The team put in an immense effort to pull together all of the elements for the weekend and it was a very proud moment for me to see the success of this. I, of course, have to mention the incredible team of staff and volunteers that work at RBBM that make everything so enjoyable and easy!!

5. What is your favourite fact, song and/or poem by Robert Burns?

- My favourite Burns song is ‘My Love Is Like A Red, Red Rose’.

6. What is your favourite Scots word?

- It has to be ‘braw’. Braw means beautiful, pretty, attractive… you could call a lassie braw or you could say “it’s a braw day the day”.

7. Do you have any special skills/hobbies/talents?

- I have played in a brass band for over 12 years and somehow manage to find the time to compete on regional and national levels in between events at the museum!

8. What is your dream vision/project?

- My dream is to visit every continent in the world – only South America and Australia to go!!

9. Who is your idol and why?

- I am going to cheat a wee bit and have two – both my grannies! Although, I am biased, they are just the BEST in the world and have taught me everything I know.

- If it was to be someone famous, it has to be the Spice Girls (again, cheating because there is five of them!) I have loved them since a really young age – GIRL POWER!

10. Where is your favourite place in the world and why?

- I have travelled to a few places but there is nothing quite like being home in Ayrshire – it’s fair braw.

Fragments

Two memorialising students from the University of Glasgow Scottish Literature department visited the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum recently to do research and blog-writing as part of their course. The following blog was researched and written by Struan McCorrisken.

Two objects in particular represent a curious facet of the cult of Burns, that is the accumulation and preservation of any and all tangible aspects of the Bards’ life. A fragment, no more than the size of a matchbox, of Jean Armour and Robert Burns’ marital bed, is encased in a large wooden discus and visible beneath a glass plate. The other is a small board containing two strips of material roughly large enough to make a small sock out of. The black silk is merely silk; and the piece of wood, just wood. What truly matters is the association these objects possess; an aspect so powerful it has driven them to be curated and displayed despite being only tiny fragments of the original whole.

This sort of collecting exemplifies precisely why these objects are valuable. Not the objects themselves, but the connection to the past they offer, the prospect of tangibility that they represent. The type of collecting and commemoration that Burns undergoes is similar almost to that of a medieval saint. This sort of fervent reverence began very soon after Burns’ death, and we may well consider it a sign that Calvinist Scotland, devoid of pomp and pageantry through the stifling presence of the Kirk and the absence of the king, was looking for something to fill the gap. This perhaps was a search for joyful veneration of a figure beyond the austere auspices of the Kirk. Burns’ own rebellious stance against much of the Kirk’s posturing may have added to that attraction. While the comparison of Burns to a saint may sound fanciful, but it’s worth considering how saints are venerated. They are commemorated with talismans, awards and honours are given in their names, statues are erected at places they had a connection to, and they have specific symbols and icons associated with them. Some have specific days they are venerated on, or specific shrines dedicated to them. We certainly manufacture talismans of Burns, as any glance around a Scottish gift shop reveals. There are awards in his name, such as the Robert Burns Humanitarian Award, and a multitude of organisations associated with him. Scotland is replete with statues and plaques of Burns, miniature shrines almost, at places associated with his life and the lives of those associated with him. Images such as the mouse, the plough and the rose are associated with Burns, arguably his very own attributes. He certainly has his own day, and the proposed desire for ritual in the Scots certainly comes to the fore here, reinforced heartily by Walter Scott’s own contributions to images of Scottish culture (tartan, kilts etc). We eat food associated with Burns and toast his “immortal memory”. Items from his life, however fragmentary, are collected and displayed in museums. A new form of reliquary perhaps?

Indeed, it may be postulated that Burns is a new form of saint for a modern, more secular, Scotland. A person of great achievement whom we admire, commemorate, and attempt to emulate. A part of this commemoration is undoubtedly the use of objects, in any condition, to help us connect with the man, long since passed.

Celebrating Scots Language

As today is International Mother Language Day, our blog post explores the history of Scots language to celebrate and promote Scottish linguistic heritage.

Scots is descended from a form of Anglo-Saxon brought to the south-east of present day Scotland by the Angles (Germanic-speaking peoples) around AD 600. The video below, from The University of Edinburgh, illustrates the origins of Scots language.

Like many European countries, early Scots speakers primarily used Latin for official and literary purposes. The earliest surviving written poem in Scots, dated to 1300, is a short lyric on the death of King Alexander III (ruled 1249-1286) which appeared in Andrew Wyntoun’s work entitled The Original Chronicle:

“Qwhen Alexander our kynge was dede, That Scotland lede in lauch and le, Away was sons of alle and brede, Off wyne and wax, of gamyn and gle. Our golde was changit into lede. Crist, borne into virgynyte, Succoure Scotland and ramede, That is stade in perplexitie”.

Yet, the first Scots poem of any length called The Brus by John Barbour was recorded in 1375. Composed under the patronage of Robert II, this poem’s tale follows the actions of Robert the Bruce through the first war of independence.

The History of Scots from the 14th– 18th Century

Between the 14th and 16th century, writing in the vernacular thrived during the reigns of James III (ruled 1460-1488) and James IV (ruled 1488-1513): Scots language truly came into its own. This period’s Scots poets are known as medieval makars or master poets, after William Dunbar’s the Lament for the Makaris, for the great literacy culture that was produced in lowland Scotland. Dunbar was a virtuosic poet with an impressive range, varying from elaborate religious hymns to scurrilous bawdy verse.

Also a makar, King James VI (ruled 1567-1625) laid down a standard writers were expected to follow in his essay on literary theory entitled The Reulis and Cautellis. However, after James VI also became James I of England in 1603, Scots language and makars were no longer supported by the Royal Court. Pre-1603, James VI voiced the differences between English and Scots but now, as ruler of the British Empire, he attempted to Anglicise Scottish society for cultural, linguistic and political union of his kingdoms. Herein, the literary activity of 17th century Scots poets declined as many, like William Drummond of Hawthornden, decided to write in English instead. This change of language was encouraged by the Royal Court alongside the larger and more lucrative English publishing markets. In Scotland, all classes continued to write and speak in Scots but, for publications writers had their texts ‘Englished’.

The Great Scots Poets of the 18th Century

In the 18th century, under the 1707 Treaty of Union, Scotland joined England to form the new state of Great Britain and poets began to utilise an increasingly bilingual literary situation. Poets combined Augustan English poetry with Scots songs, tales and older poems to create a vernacular revival in Scots verse. The work of poets such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns demonstrated the popularity and poetic nature of Scots as a literature. These poets, expressing a national identity, produced poems that were, and continue to be, widely read.

Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) was born in Lanarkshire and educated at Crawfordmoor Parish School. Following his mother’s death, Ramsay moved to Edinburgh to study wig-making and eventually opened a shop near Grassmarket. He was an eminent portrait painter and began writing poetry from the early 1700s. In 1721, Ramsay published his first volume as a blend of English language and Scots poems. He abandoned the wig-making trade to become a bookseller, opening a shop near Edinburgh’s Luckenbooths- this also became Britain’s first circulating library. Ramsay’s works, such as Tea-Table Miscellany (1724), The Ever Green (1724) and The Gentle Shepard (1725), laid the foundations for Scot writers like Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns.

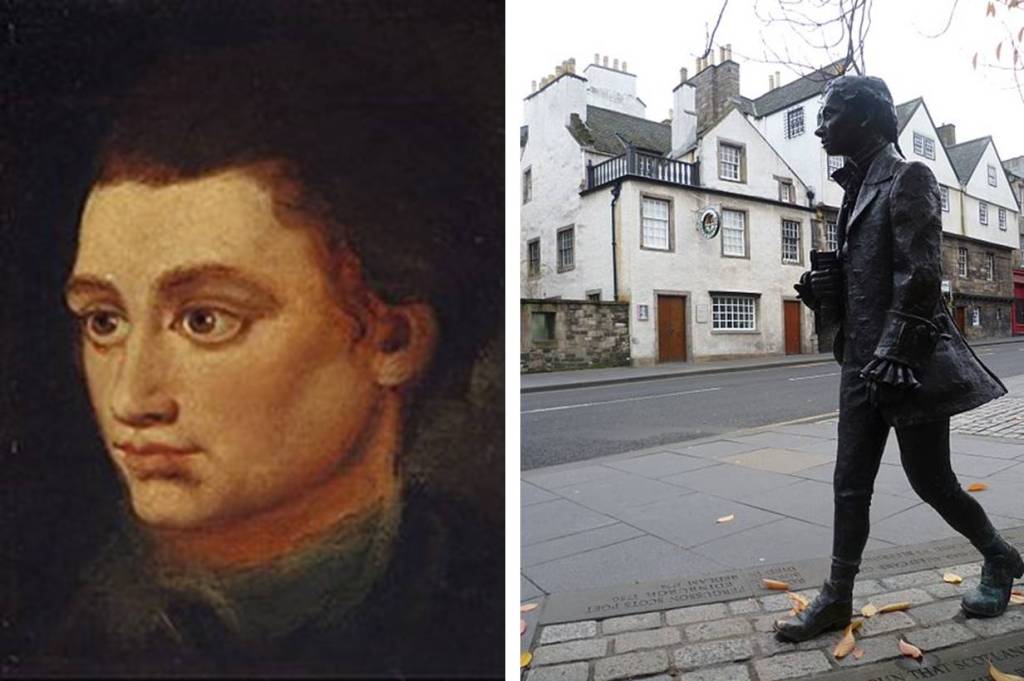

Robert Fergusson (1750-1774) was born in Edinburgh’s Old Town to Aberdeenshire parents. He attended St. Andrews University and became infamous for his pranks- for which he came close to expulsion. In 1771, Fergusson anonymously published his first trio of pastorals entitled Morning, Noon and Night. He amassed an exquisite range of about 100 poems, developing existing literary forms and contributing to contemporary debate. Aged 24, Fergusson experienced a fatal blow to his head falling down a flight of stairs, he was deemed ‘insensible’ and transferred to Edinburgh’s Bedlam madhouse where he later died. In 1787, Robert Burns erected a monument at his grave, commemorating Fergusson as ‘Scotia’s Poet’.

Robert Burns called Fergusson “my elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in muse”. Clearly inspired by the poet, Burns adopted both Fergusson and Ramsay’s use of Scots words and verse to master his own poetry and advance Scots literature. In doing this, Burns became Scots language’s most recognised voice with poems and songs read and sung worldwide. The Robert Burns Birthplace Museum displays volumes and poems by Fergusson and Ramsay (below), highlighting the similarities to Burns’ work in terms of tone, format, subject matter and, of course, Scots language.

The History of Scots Post-Burns to the Present

In the 19th century, building on the work of Scots poets, novelist began combining English and Scots in their writings. More often, English was used for the main narrative and Scots voiced Scots-speaking characters or short stories.

After this period, the 20th century saw a radical renaissance of Scots poetry, primarily through Hugh MacDiarmid (pen name of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid’s work The Scottish Chapbook, reassessed early Scots verse by using words from across different regions. Later, Edinburgh poet Robert Garioch reopened links to the Scots verse MacDiarmid devalued. Garioch, to a greater extent than MacDiarmid, developed a form of Scots united to any particular locality and produced a model that future writers could follow. Other 20th century poets, included Edwin Morgan, and his translation of Vladmir Mayakovsky’s poetry into Scots, as well as Tom Leonard’s Six Glasgow Poems.

Today, Scots language continues to thrive. In communities across Scotland, people use Scots as a language to write and speak. As the 2011 Scottish Census reported, there are 1.5 million speakers of Scots within Scotland, which is around 30% of the population.

So, why not challenge yourself? And join them? To celebrate Scots language and International Mother Language Day, learn a new word or a new phrase or more!

Check out the links below for more ways to learn Scots:

- On social media, we run a Scots word of the week campaign, encouraging our followers to guess and discuss what they mean. We often get international audiences commenting on the similarities between Scots and various European languages. Check it out on Facebook (@RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum) and Twitter (@RobertBurnsNTS).

- Search our blog for Scots language posts: https://burnsmuseum.wordpress.com/tag/scots-language/

- For Scots on Twitter, take a look at these pages: @lairnscots, @scotslanguage, @ScotsScriever, @tracyanneharvey @rabwilson1 and @TheScotsCafe.

- Join the Open University’s FREE online Scots language and culture course: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705

- Or, check out some of these websites: https://www.scotslanguage.com/

https://www.gov.scot/policies/languages/scots/

http://www.cs.stir.ac.uk/~kjt/general/scots.html

https://education.gov.scot/improvement/Documents/ScotsLanguageinCfEAug17.pdf

Gang oan, gie it an ettle!

A Blether Aboot the Scots Leid!

Fir twa hours oan Saturday 19th Oct masel an hawf a dozen ithir fowk wi a birr fir the Scots tongue speirt awa aboot oor language, or leid, in the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum biggin.

We blethert aboot hoo we feel whin we hear fowk yaisin Scots words, yon sense o connection that we feel an hoo the leid taks us back tae guid memories o whin we wir weans. It’s aa aboot hoo oor brains are wired an hoo certain pathways in oor harns licht up whin we hear language that we ken. The Scriever fir Scotland, Michael Dempster, explains this in a Ted Talk oan You-Rube, which is weel worth a wee swatch.

Gien that this is the International Year o Indigenous Languages, we jaloused aboot hoo maist linguists gree that Scots is a leid in its ain richt an hoo Scots is kent by oor ain government an the European Commission as wan o the 3 indigenous leids o Scotland, alang wi English an Gaelic.

We luiked at hoo Scots language hus evolved owre the centuries wi Brythonic, Anglo-Saxon, Norwegian an Scandinavian, French an Auld English influences as weel as fae the Celts an the Picts. An hoo, it’s kent as a Germanic leid wi close ties tae Auld English.

We speirt aboot hoo oor Scots leid hus maistly been a spoken leid, due tae hoo historic documents wir aften scrievit in Latin an French. Poetry hooivver hus aye buin scrievit in Scots, stertin wi the magneeficent poem BRUS scrievit aboot Robert the Bruce by John Barbour in the 1370’s.

We spaik aboot hoo, eftir the union o Scotland an England, the nabbery stertit tae learn tae read an scrieve in English, we jaloused that mibbe they thocht this wuid be beneficial tae them in terms o trade, status an siller. White’er thaur thochts wir, the ootcome wis a dingin doon o the Scots leid an the stairt o a penchant tae tell fowk speikin Scots tae “speik properly”.

We spaik o the Scottish enlightenment in the 18th century whin makars sic as Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson an Robert Burns hud the smeddum tae scrieve in Scots tae mak siccar the Scots Leid wis uphaudit tae this day. We jaloused that aiblins oor bonnie leid wid hae bin lost itherwise. We spaik o hoo, nooadays, wi the world gaun the way its gaun at the meenit, we are hell bent oan preserving oor leid, itherwise, wi media influences we micht aa end up wi transatlantic accents!! We got yokit in aboot this, speirin aboot hoo oor weans are sayin words lik “Trick or Treating” insteid o “gaun guisin”!!

We spaik aboot hoo literature, parteecularly fir weans, is being scrievit an owerset intae Scots mair an mair an hoo this is a gey guid way o airtin fir the future.

We aa hud different life experiences and thochts but we aa agreed that we want tae preserve oor rich an descriptive Scots leid an pass it oan tae oor weans an granweans.

A wheen o Scots words hae been dinged doon as bein “slang” an we luiked at some examples an whaur they micht originate fae;

- “A WEE STOATER” – meanin “first class” or a fine example o somehin, eg, a “stoater” o a goal, or a wee smasher. Nae doot related tae STOTTIT – BOUNCED and mibbe even tae STOT – an auld Scots word for a bullock.

- “UP THE SKYTE” – meanin pregnant. KYTE wis originally the Scots word fir belly. So if somebody’s “skyted” their belly hus gotten big, they are pregnant. Also the medical term for fluid in the abdomen is ASCITES (latin) from ASKITES (Greek).

- SCUNNERT – as in “ocht ah’m fair scunnert the day, ah cannae get oot ma ain road”, auld Scots an Northern English word, Robert Fergusson an Robert Burns baith yaisd it in their poetry. Literal meanin wis originally tae flinch / tae shrink back. Noo means “fed up.” Comes fae the 14TH century Norse word SKONERON.

- BLETHER – meanin tae chat, “hae a wee blether” or someone who is “a wee blether”, wee chatterbox, Originated fae the auld Norse word blathra or blaora.

- HUNKERS– ie “doon oan yir hunkers”, meanin squattin doon – Dutch or German in origin.

- WINTER DYKES – clothes horse – in the summer fowk yaist tae pit thaur claes owre stane dykes tae dry, as they hud nae washin lines, so in the winter they wuid dry the claes in the hoos, in front o the fire owre a wuiden frame, which they caad the “winter dykes”.

- SMEEKIT – nooadays meanin steamin fu’, intoxicated. Originates fae auld Scots word SMEEK meanin smoke or fumes so, in the case o the modern yis o SMEEKIT, the fumes comin fae somebody intoxicated wi alcohol.

- GUISIN – comes fae Scots an North England meanin “disguised as”. Swipperly bein taen owre by “Trick or Treating”.

- OXTER – armpit. Norse in origin – Dutch word is Oksel.

- REDD UP – as in “awa an redd up yir room”, yaisd in Scotland an Northern England, comin fae the word “rid”, “get rid of”.

- BARE SCUDDIE – goes back tae the 18 hunners, meanin nooadays naked, but originally meanin a wee fledgling burd that’s no got oany feathers.

We then brainstormed some mair Scottish words an phrases lik:

- TUMMLE THE CRAN(forward roll)

- FANKLE(mixed up), eg, Ah wuid get intae a fankle if ah tried tae dae a tummle the cran!

- GRUMPHIE (pig)

- PUNTIE UP (help tae sclim up)

- HUNTIGOWK (April fools day)

- BOAK (be sick)

- BRACE (mantelpiece)

- OWRE THE THRAPPLE (doon the throat), we hud a guid laugh mindin oor granny’s gien us butterbaas tae cure a sair throat! Gadz!

Eftir that we compared some scrievins in Scots Leid, yin lass read a poem scrievit in Doric fae Lallans Scots leid journal, an this lead tae a blether aboot Sheena Blackhall’s braw Doric poetry, sic as “The Check Oot Quine’s Lament.” Anither lass hud owreset Wordsworth’s “Composed Upon Westminster Bridge” intae Scots an anither lass hud us heehawin an laffin at some o her social media posts in Scots.

We hud a wee laugh at hoo a few o us in the group hud been threatened wi elocution lessons as weans. We also speirt aboot hoo Scots words vary fae airt tae airt an hoo we can get crabbit an frustrated aboot hoo tae spell Scots words, gien we huv never buin tocht this an are self tocht. This is whaur guid scrievins come intae thaur ain an we hud a luik at James Andrew Begg’s buik “The Man’s The Gowd for a that”, which ah hae read recently an it baith brocht back words ah hud forgotten aa aboot an tocht me new wans tae. As Scots Scriever Michael Dempster telt us in his Ted Talk “it fair lit up the pathways in ma harns.”

We read a cutty extract fae chapter 9, “The Killie Fleshers” pages 108 – 109, based oan a fictional blether set in Kilmarnock in 1786, atween a fermer chiel an the printer o the Kilmarnock First Edition, Johnie Wilson, wha is speirin aboot “this Rob the Rhymer” an hoo “at the stert ah wis sweirt tae tak it on, fir his verses are aa in the Scotch tung…since aa thaim that can afford tae buy buiks are learnin tae speak in English”. We felt this extract wis relevant tae the pynt we wir makin earlier aboot hoo Burns wis instrumental in preservin the Scots Leid an hoo he mak’d siccar it wisnae gauntae be dinged doon. No on his shift. An we are fair gled that Wilson did “tak it oan”.

At the hinneren oor tungs taiglt us that much that we didnae dae oany scrievin!! Hoo an ever, we greed that it hud been an awfy guid blether an we’ll dae it again at the neist Scots Leid wirkshoap oan Setturday 09.11.19 1pm tae 3pm in the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum biggin.

Aabody welcome. Aefaulds .

Tracy Harvey, Resident Scots Scriever fir Robert Burns Birthplace Museum

Burns on Beasties

On the BBC’s website it is listed that there are 118 poems written by our beloved bard Robert Burns with the theme of nature, however, I would argue that there is so many more as nature – a subject which was very close to his heart – is inextricably intertwined in a number of his works.

The reason nature is a genre featured so heavily within Burns’s works can be traced back to his upbringing and lifestyle. Being born in the but-and-ben Burns Cottage in Alloway, he was introduced to the ways of farmlife from childhood. He worked with his family closely there and at multiple farms thereafter such as Mount Oliphant and Lochlea Farm. Burns and his brother Gilbert even farmed at Mossgiel Farm when his father died. He did not just have connections with the land in his younger years but as an adult as well as he worked as a farmer alongside his career as a poet and songwriter. His last farming endevaour was at Ellisland Farm in Dumfrieshire. His rural upbringing and argicultural employment earned him his nickname as “The Ploughman Poet” by the artistocratic society of Edinburgh. Burns lived in Edinburgh for only two years – the city which he described as “noise and nonsense” – to return to his rural roots.

Firstly, I would ask: what is nature? It is defined as the phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals and the landscape. Burns did not neglect any of these three aspects and used them frequently as the inspiration of his works. He did various works which refer to plants such as To a Mountain Daisy, My Luve is Like a Red Red Rose and The Rosebud. Some of my personal favourite works of Burns which talk about other environmental features include Sweet Afton (about a river) and My Heart’s in the Highlands (which of course is about one of the most rugged, scenic and breath-taking landscapes in the world).

However, what this blog will mainly focus on is that Burns was most notably an animal lover. This is conveyed in his works On Glenriddell’s Fox Breaking his Chain, The Wounded Hare, Address to a Woodlark, The Twa Dogs, To a Louse and the renowned and much adored To a Mouse. This last poem – which was written in 1786 and published in the Kilmarnock Edition – is a perfect example of Burns’s humanity as this poem reflects his concern for animal welfare, his consciousness of humankind’s effect on nature and has empathy for a small creature which is widely considered as “vermin”. This was very ahead of his time and is a concern that is currently proving to be a huge issue as more and more animals become extinct because of human’s destructive actions in the twenty-first century.

The Twa Dogs poem, written in 1796, is another great work of Burns’s which gives the two dogs human-like intellect and the ability to express themselves as it has an upper-class pedigree, Caesar, and an ordinary working collie, Luath, who chat about the differing lives of the social classes. The name “Luath” comes from Ossian’s epic poem Fingal. The Twa Dogs immortalizes Burns’s own dog Luath who came to a cruel end. On the morning of 13th February 1784 Robert and his sister Isabella were distressed to find the poisoned body of Robert’s dog Luath outside their door – the act of a vengeful neighbour. Arguably, Burns intended this poem as a memorial to his canine friend.

An example of one of Burn’s lesser-known poems is The Wounded Hare which was written in 1789. Below are the first three stanzas out of five that complete this poem:

Inhuman man! curse on thy barb’rous art,

And blasted be thy murder-aiming eye;

May never pity soothe thee with a sigh,

Nor ever pleasure glad thy cruel heart!

Go live, poor wand’rer of the wood and field!

The bitter little that of life remains:

No more the thickening brakes and verdant plains

To thee a home, or food, or pastime yield.

Seek, mangled wretch, some place of wonted rest,

No more of rest, but now thy dying bed!

The sheltering rushes whistling o’er thy head,

The cold earth with thy bloody bosom prest.

The word choice makes the moral message of this poem is clear: Burns is vehemently opposed to shooting. The passion and intensity of Burns’s thoughts on this is quite surprising as one would think that as a farmer he would be used to or even dependent on killing animals, however, meat consumption was not as prominent in the eighteenth century as farm animals were only killed for food in old age or special occasions. The family’s provision of milk, cheese, butter and wool came directly from their own animals, and the health and wellbeing of these creatures were paramount. Furthermore they would share the same roof over their heads with them, thus creating strong bonds with their farm animals, and apparently Burns lost his temper with a farm-worked once when the man did not cut the potatoes small enough and Burns was frantic that the beasts might choke on them.

Below is the third stanza of the powerful poem On Glenriddell’s Fox Breaking His Chain written in 1791:

Glenriddell! Whig without a stain,

A Whig in principle and grain,

Could’st thou enslave a free-born creature,

A native denizen of Nature?

How could’st thou, with a heart so good,

(A better ne’er was sluiced with blood!)

Nail a poor devil to a tree,

That ne’er did harm to thine or thee?

Again, you can clearly see that Burns is opposed to the cruel treatment of a “free-born creature” and is in disbelief of the actions of the good-hearted Glenriddell’s actions.

However, one could argue that nature was so deeply rooted in Burns’s psyche – and he quite literally was surrounded by it living on a farm – that he could not escape from being inspired to write about it. An example of this is in his masterpiece Tam o’ Shanter. It is an epic narrative poem written in 1790 which features folklore, superstition, witchcraft and gothic themes… but it also has one of his most poignant and beautiful quotes in which Burns really philosophically details the nature of nature:

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white–then melts for ever;

Or like the borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.–

Nae man can tether time or tide;

The hour approaches Tam maun ride;

Burns is saying that nature’s beauty is wistful, forever-changing and is out of the control of humankind as he insightfully states “nae man can tether time or tide”.

In terms of this poem, another point is worth mentioning: the hero of this tale is a horse. Again Burns’s admiration and respect for animals is encompassed in the heroism of Meg, Tam’s horse, who against all odds does get him home in one piece although the same cannot be said for her. Burns was a brilliant horse-rider and would have relied heavily on his four-legged companion as a mode of transportation to socialise, to plough fields and to work as an excise man.

All in all Burns would have been regarded nowadays as an advocate for animal welfare and his works which have animals or nature at their core reflect his love for nature and are some of his most passionate, most thought-provoking and most heart-rending.

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)

‘The descendant of the immortal Wallace’

Throughout his life, Robert Burns was inspired by women. He grew up listening to the Scottish songs and folklore of his mother, Agnes, and distant cousin, Betty Davidson; fell in love time and again with a new bonnie lassie; and fathered several much loved daughters of his own who inspired his affections and poetry. Few relationships however are as well documented or as important to his works as his friendship with Mrs Frances Anna Wallace Dunlop, whose support and patronage were invaluable to the Bard for the majority of his publishing life.

Born in 1730, Frances Anna Wallace was the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas Wallace of Craigie and Dame Eleanora Agnew. Sir Thomas claimed to have been a descendant of Sir Richard, cousin of William Wallace – a connection which Burns was later delighted by. At the age of 17, Frances married John Dunlop of Dunlop and the couple went on to have 7 sons and 6 daughters. Their happiness was not to last however, as John died in 1785 resulting in Frances falling into a ‘long and severe illness, which reduced her mind to the most distressing state of depression’. This would have been an affliction Burns was also all too used to.

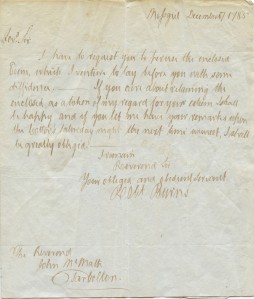

It was as she was recovering from this illness that a friend gave her a copy of The Cotter’s Saturday Night to read. So delighted was she with it that she sent, according to Gilbert Burns, ‘a very obliging letter to my brother, desiring him to send her half a dozen copies of his Poems, if he had them to spare, and begging he would do her the pleasure of calling at Dunlop House as soon as convenient’. The Bard responded by sending her 5 copies of his Kilmarnock Edition and a promise to call on her on return from his trip to Edinburgh. It was the start of a very important friendship.

Burns visited Mrs Dunlop at least five times throughout his life, and wrote more often to her than any other correspondent, sending her copies of his poems and drafts of letters intended for others. She in return wrote to him of her family troubles, as well as counselling him on career choices and urging him to modify what she described as his ‘undecency’ in relation to his affairs with women. She described his correspondence as ‘an acquisition for which mine can make no return, as a commerce in which I alone am the gainer; the sight of your hand gives me inexpressible pleasure…’ It would appear, in saying this, that she underestimated the value Burns placed on her friendship, as his increasingly desperate attempts to illicit a response from her after their falling out demonstrate.

This falling out occurred in 1794. With two of her daughters marrying French refugees and various members of her family having army connections, Mrs Dunlop had hinted at her disapproval of Burns’s apparent sympathies with revolutionaries in France in previous correspondence. He failed to take the hint and wrote in a letter of December 1794, referring to King Louis and Marie Antoinette, ‘What is there in the delivering over a purged Blockhead & an unprincipled Prostitute to the hands of the hangman, that it should arrest for a moment, attention in an eventful hour…?’ This offence was a step too far.

Burns sent Mrs Dunlop two further letters without reply, apparently completely oblivious to what could have caused her anger. ‘What sin of ignorance I have committed against so highly a valued friend I am utterly at a loss to guess’ he wrote in January 1796, ‘…Will you be so obliging, dear Madam, as to condescend on that my offence which you seem determined to punish with a deprivation of that friendship which once was the source of my highest enjoyments?’ On receiving no response, his final letter to her was sent just days before his death informing her that his illness would ‘speedily send me beyond that bourne whence no traveller returns’ and bestowing praise upon her friendship. It is believed that she did relent on receiving this, and one of the last things Burns was able to read was a message of reconciliation from her.

Mrs Dunlop survived the poet by another 19 years, dying in 1815. Her friendship and patronage were hugely valued by Burns, and her impact on the poet’s life and works should be regarded as just as important as that of other key women in his life. She is buried in Dumfries, Scotland but her words and thoughts live on in her letters to Scotland’s National Bard.

Forging the Bard

From the moment of Burns’s death in 1796, a hunger to obtain original versions of his works, letters and personal items began. Naturally, this led to a number of unscrupulous individuals creating forgeries, or passing off unconnected objects as having belonged to the Bard. Few were as prolific or notorious however as one Alexander Howland Smith, known as ‘Antique Smith’, a Scottish document forger of the late C19th whose efforts are now collection items in their own right.

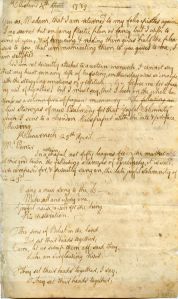

Born in 1859, Smith was forging documents in Edinburgh by the 1880s, and began selling his forgeries in 1886. He frequented second hand bookshops, purchasing volumes of old books with blank fly leaves, which he then insisted upon carrying home himself rather than asking for them to be delivered – despite their weight (a practise many bookshop owners found strange!). From these blank fly leaves, Smith forged poems, autographs and historical letters purportedly written by a number of historical figures including Mary Queen of Scots, Walter Scott and Burns himself. He gave his documents an antique appearance by dipping them in weak tea!

Things started to go wrong for Smith when manuscript collector James MacKenzie put some of the letters in his ‘Rillbank Collection’ up for auction in 1891, and the auctioneer himself cast doubt on their authenticity by refusing to verify their provenance. A little while later MacKenzie published a letter, supposedly written by Burns, in the Cumnock Express. After a bit of research, one reader discovered that the recipient of this supposed letter, John Hill, had never actually existed, throwing doubt on the entire Rillbank Collection. MacKenzie later published two ‘Burns’ poems in the same paper, only to discover that one of them had been written when Burns was only 7 by an entirely different poet! Other forgeries were discovered in the collection of an American, who had purchased letters from Edinburgh manuscript collector James Stillie.

By now, word was spreading about the forgeries. In 1892, The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch published an article on the issue, and a reader recognised the handwriting on the facsimiles included as that of Smith, at that time working as chief clerk for a lawyer, Thomas Henry Ferrie. Smith was duly arrested and his trial began on June 26th 1893.

Smith was charged with selling forgeries under false pretences. He was found guilty, but the jury recommended leniency and he was sentenced to 12 months. Experts later said that some of his forgeries were not of particularly high quality – often they were dated after the death of their supposed writer, or created using modern paper or writing tools. It is more than possible that many of those who sold his forgeries on would have been fully aware that they were not genuine. It is unknown exactly how many of ‘Antique’ Smith’s forgeries are still around, but we do know that we have some of them in our collection!