Exhibition

Scots Leid: It Isnae Deid Yit!

Scots Language: It Isn’t Dead Yet!

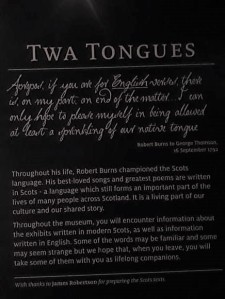

We had a guest speaker at one of our weekly Highlight Talks on the 13th February 2019, a Mr Derek Rogers, who delivered a presentation titled “Did Robert Burns Use Scots and Does the Scots Language Exist?” It proved to be an interesting event – the Scots language tends to be an engaging albeit sometimes controversial topic – and amongst the following debate that ensued at the end of the talk, a visitor quite rightly stated that they had observed that the Scots language seems to be being lost, through younger generations not using or understanding it, as older generations of Scots once did. There are several reasons why this is the case (and is worthwhile of another separate blog within itself) but the visitor then asked the audience: what could be done to keep it alive? Thus, I felt inspired to write a piece on how we provide the perfect opportunity for younger generations to learn more about the Scots language by visiting us with their school and/or their families.

When you google “the Scots language it states: ‘Scots is one of three native languages spoken in Scotland today, the other two being English and Scottish Gaelic. Scots is mainly a spoken language with a number of local varieties, each with its own distinctive character.’ That in a nutshell is the Scots language.

It is an essential element of the educational experience we provide here at RBBM because Robert Burns chose to use both Scots and English to write his works in. To quote our bard, he said “I think my ideas are more barren in English than in Scottish.” Thus, it is an important part of the Burns legacy.

Scots is recognised as a language by our governments and we believe it makes up an important part of Scotland’s heritage, it is in our strategy to promote Scots, and furthermore, the learning and sharing of languages could not be more relevant in the 21st century as our world becomes more globalised and international (there is research that proves that there are multiple benefits of being bilingual).

In regards to our formal school workshops, we have Scots language elements running through all of them; however, three in particular have Scots at their core. Tim’rous Beasties, which is suitable for Nursery – Primary 1 aged children, learn about the poem Tae a Moose and the Scots words for the song Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes – or Heid, Shouthers, Knaps n Taes – as well as animals native to Scotland. Did you know that the Scots word for badger is brock? Another workshop tailored for the same age group is Cantie Capers which focuses on farmyard tools and animals assisted with the setting of the Burns Cottage. Then for Primary 5 – 7 aged pupils, we have Being Burns, which uses costume and the Burns Cottage to assist discussing Scots words for numerous everyday items like peenies, bunnets, luggies and kirns.

Furthermore, we have Scots interpretation throughout our museum, play park and the Burns Cottage itself. Visitors can read and learn the meanings of words Burns and his family members would have undoubtedly have used.

Do you live outside of Scotland? Or don’t envision being able to visit us anytime soon but want to learn more about Scots? Then you might be interested in knowing that we also run a Scots word of the week campaign on our Facebook (@RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum) and Twitter (@RobertBurnsNTS) pages, encouraging our followers to guess what they mean or to discuss if or how they use the words. We often get international audiences commenting on fond memories these words bring to mind or the similarities between Scots and various other European languages like Dutch, Norwegian, Danish and German.

Other pages worth a follow on Twitter include: @lairnscots, @scotslanguage, @ScotsScriever and @TheScotsCafe.

Also, there is a Scots Dictionary app you can download onto your phone: type ‘Scots Dictionary for Schools’ and you’ll see the Abc Scottish flag icon.

So, we absolutely hope that by visiting us or following our social media channels, you feel inspired to use Scots: to celebrate it, discuss it and learn about it. If it was good enough for Burns, then it is good enough for our bairns!

By Parris Joyce, Learning Officer at RBBM.

PS. The irony of this blog being in English when it is discussing and celebrating the Scots language was too great to not act upon. So, here is the blog in Scots for you to read and enjoy!

Scots Language: it isnae deid yit!

We hud a guest speiker at ane o oor weekly Heichlicht Talks oan the 13th Februar 2019, a Mr Derek Rogers, wha gien an ootsettin entitled “Did Robert Burns Use Scots and Does the Scots Language Exist?” It pruived tae be an interestin event – the Scots leid is aye-an-oan a thocht provokin topic that e’en these days can heize up a guid gaun collishangie amangst oor audiences – at the hinnerend o the ongauns ane o wir veesitors quite richtly stated that they hud observed that the Scots leid seemt tae be gettin loast due tae oor young fowk no uisin or unnerstaunin it the same as aulder generations o Scots aince did. Thair a hauntle o raisons why this micht be the case (an this micht be warthy o anither separate blog in itsel!) but the veesitor then spiert o the audience: whit micht be duin tae keep the Scots leid alive? Syne, then ah felt inspired tae scrieve a piece oan hou we provide the perfit chaunce fir younger generations tae lairn mair anent the Scots leid bi veesitin us here at the RBBM wi their schuil and/or their faimilies.

When ye google “the Scots language” it kythes: ‘‘Scots is one of three native languages spoken in Scotland today, the other two being English and Scottish Gaelic. Scots is mainly a spoken language with a number of local varieties, each with its own distinctive character.’ That, short an lang, is the Scots language or leid.

Scots is a perteecular pairt o the educational ongauns we provide here at RBBM because Robert Burns chose tae uise baith Scots an English tae scrieve his warks. Tae quote oor bard, he said “I think my ideas are more barren in English than in Scottish.” Thus, Scots is an aefauld important pairt o the Burns legacy.

Scots is offeeshully recognized as a leid bi oor governments an it is oor thocht that it maks up a verra important pairt o Scotland’s heritage. It kythes in oor strategy to promote Scots, an forby, the lairnin an sharin o languages cuidnae be mair relevant in the 21st century as oor warld turns e’en mair globalised an international (thair’s alsae an awfie loat o faur-i-the-buik resairch that ettles that there are a wheen o benefits fir us aa frae bein bilingual).

In regairds tae oor formal schuil warkshoaps, we hae Scots leid elements rinnin throu the hail jing-bang o thaim; houanevir, three in perteecular hae Scots at their hairt. Tim’rous Beasties, that’s suitable fir Nursery – Primary 1 aged weans, whaur they lairn aboot the poem Tae a Moose an the Scots wirds fir the sang ‘Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes’ – or Heid, Shouthers, Knaps an Taes. Forby this we alsae teach thaim the nems fir native animals o Scotland. Did you ken the Scots wird fir a Badger is a Brock? Anither warkshoap tailored fir the samen age group is Cantie Capers , this focuses oan fairmyaird tools an animals conneckit athin the settin o the Burns Cottage. Syne, fir Primary 5 – 7 aged weans, we hae Being Burns, that uises costumes an the Burns Cottage tae gie a heeze in the discussion o Scots wirds fir a thrang o ilk-a-day knick-knackets, lik peenies, bunnets, luggies an kirns.

Forby, we hae Scots information athort oor museum, its playpark an the Burns Cottage itsel. Veesitors can read an lairn the meanins o wirds Burns an his faimily wid nae dout hae uised in their ilka day spik.

Dae you bide furth o Scotland? Or dinnae ettle oan bein able tae veesit us ony time suin but wid fair like tae lairn mair anent Scots? Then ye micht be keen tae luik the gate o some o the ither ongauns we hae anent the Scots leid; we rin a Scots wird o the week campaign oan oor Facebook (@RobertBurnsBirthplaceMuseum) an Twitter (@RobertBurnsNTS) pages, giein a heeze tae oor follaers tae guess whit the wirds mean or collogue oan hou they micht uise the wirds. We gey aften get international audiences haudin furth oan aefauld memories that these wirds bring tae mind, or the seemilarities atween Scots an sindrie ither European leids, sic as Dutch, Norwegian, Danish and German. Ither pages warth follaein oan Twitter include: @lairnscots, @scotslanguage, @ScotsScriever and @TheScotsCafe.

Alsae, there is a free Scots Dictionary app ye can dounload oantae yer phone that is byordnar uisefu fir aa age groups. Jist type in ‘Scots Dictionary for Schools’ in yer app store an ye’ll see the Abc Scottish flag icon.

We fair howp that bi veesitin us or follaein oor social media channels ye wull feel inspired tae uise Scots: tae celebrate it, discuss it an lairn aboot it. Gin it wis guide enow fir Burns, then it is guid enow fir oor bairns!

Owerset intil Scots by RBBM Scots Scriever an Poet Rab Wilson.

Haud forrit – an keep a guid Scots tung in yer heid!

Sites warth veesitin wi regairds tae the Scots leid:

- https://education.gov.scot/improvement/documents/scotslanguageincfeaug17.pdf

- https://www.scotslanguage.com/

- https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2011/may/20/the-return-of-scots

- https://www.gov.scot/publications/scots-language-policy-english/

- http://www.robertburns.org.uk/scots_tongue.htm

- https://burnsmuseum.wordpress.com/2017/10/09/scots-language-at-rbbm/

- http://www.burnsmuseum.org.uk/scots-language-strategy/

An Insight Into Ae Fond Kiss

Ae Fond Kiss is one of Robert Burns’s most famous love songs, one that outlines not the joy that love can bring but the acute pain of a broken-heart. It is moving, emotional and tender.

The song was written in 1791 and sent in a letter to Mrs Agnes McLehose (addressed as ‘Nancy’ in this instance). Burns met Agnes (1758–1841) in Edinburgh when she arranged an introduction to the bard by a mutual friend, Miss Erskine Nimmo. They engaged in an intense yet unconsummated love affair, largely through a series of passionate letters exchanged between the two.

Following Burns’s departure from Edinburgh in 1788, the bard’s relationship with Agnes suffered owing to his reunion with and eventual marriage to Jean Armour, not to mention an affair with Jennie Clow, Agnes’s maid, which resulted in a child. In 1792, Agnes returned to the West Indies at the request of her estranged husband (only to return after finding out he had started another family). Upon learning of her planned departure, Burns was inspired and sent her the heart-rending song Ae Fond Kiss. The song was first published in 1792 in James Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum (which can be seen on display at RBBM).

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever;

Ae fareweel, alas, for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

Who shall say that Fortune grieves him,

While the star of hope she leaves him?

Me, nae cheerful twinkle lights me;

Dark despair around benights me.

I’ll ne’er blame my partial fancy,

Naething could resist my Nancy:

But to see her was to love her;

Love but her, and love for ever.

Had we never lov’d sae kindly,

Had we never lov’d sae blindly,

Never met-or never parted,

We had ne’er been broken-hearted.

Fare-thee-weel, thou first and fairest!

Fare-thee-weel, thou best and dearest!

Thine be ilka joy and treasure,

Peace, Enjoyment, Love and Pleasure!

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever!

Ae fareweeli alas, for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

In the third verse, the speaker reflects upon his infatuation with Nancy, suggesting that he could not resist her charms. Notice how the emphasis is on her appearance rather than other attractions: “But to see her was to love her”. Nancy may have had a great personality, came from a respectable background but here the speaker is idealizing the external beauty only. This is classic Burns as he himself and some of his works do have undertones of machoism, for example, cheating on his wife and in Tam o’ Shanter with Kate at home ‘nursing her wrath’ whilst Tam is drunk, flirting with Kirkton Jean and eyeing up Nannie!

The language is relatively straightforward and is polished compared to some of Burns’s other poems in Scots. Scots pronunciations are used throughout – for example, ‘nae’ for ‘no’ and ‘weel’ for ‘well’. Scots terms are limited to ‘ilka’ for ‘each’ or ‘every’ in the fifth verse. Perhaps Burns’s reasoning for this is because Nancy was included in polite 18th century society in Edinburgh and would have spoken in English rather than Scots?

The heavily romanticized and iconic quote from this poem is:

But to see her was to love her;

Love but her, and love for ever.

This would make any romantic swoon but one should keep in mind that on a biographical level, Burns writes to Agnes long after their initial infatuation. We know that Burns had returned to his own wife and he had also got Agnes’ servant pregnant. Can we still see this song as a true outpouring of emotion? Or, should we see it as a carefully crafted piece of poetry? I think it is both – Burns had a tendency to have bursts of illogical emotion when it came to his love affairs, like confessing undying love to one whilst happily married to another, but that does not mean it was not real to him – but I do not think it matters either way you interpret it. It is what it is: and that is a beautiful love song.

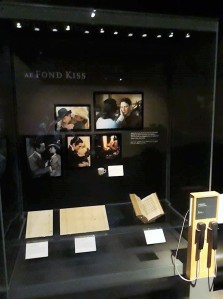

In the main exhibition space within the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, there is a display case dedicated to Ae Fond Kiss which has four objects on display as well as an interesting contemporary interpretation of the work through images.

There are five snapshots taken from Hollywood movies that are about unrequited love: Romeo and Juliet, Casa Blanca, Gone with the Wind, Brokeback Mountain and Atonement. This reference to popular culture throughout the 20th and 21st centuries is a great way to convey how love and heart-ache has and always will be a topic of interest and an inspiration for artists no matter their medium.

Also, there is a teacup that belonged to Agnes which is used to represent the different social classes of Burns and her; a letter from Burns to Agnes saying he has included a song for publication (i.e. Ae Fond Kiss); another letter from Burns to Agnes in which they use their code names ‘Sylvander’ and ‘Clarinda’ because though separated, Agnes was deeply concerned with propriety and confidentiality; and Ae Fond Kiss shown in the Scots Musical Museum book.

Other objects within the museum’s collection which are worth noting are the silhouette miniature of Agnes, the pair of wine glasses Burns gifted Agnes and a letter from Agnes to Burns.

1878

Creator:

Alexander Banks Artist: John Miers,

Object No.:

3.8126

You can listen to a beautiful rendition of Ae Fond Kiss here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ax021N4iaFU

By Parris Joyce (Learning Trainee)

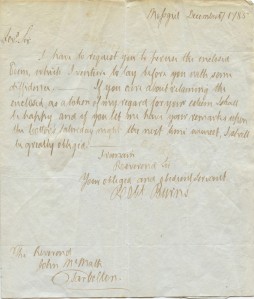

Forging the Bard

From the moment of Burns’s death in 1796, a hunger to obtain original versions of his works, letters and personal items began. Naturally, this led to a number of unscrupulous individuals creating forgeries, or passing off unconnected objects as having belonged to the Bard. Few were as prolific or notorious however as one Alexander Howland Smith, known as ‘Antique Smith’, a Scottish document forger of the late C19th whose efforts are now collection items in their own right.

Born in 1859, Smith was forging documents in Edinburgh by the 1880s, and began selling his forgeries in 1886. He frequented second hand bookshops, purchasing volumes of old books with blank fly leaves, which he then insisted upon carrying home himself rather than asking for them to be delivered – despite their weight (a practise many bookshop owners found strange!). From these blank fly leaves, Smith forged poems, autographs and historical letters purportedly written by a number of historical figures including Mary Queen of Scots, Walter Scott and Burns himself. He gave his documents an antique appearance by dipping them in weak tea!

Things started to go wrong for Smith when manuscript collector James MacKenzie put some of the letters in his ‘Rillbank Collection’ up for auction in 1891, and the auctioneer himself cast doubt on their authenticity by refusing to verify their provenance. A little while later MacKenzie published a letter, supposedly written by Burns, in the Cumnock Express. After a bit of research, one reader discovered that the recipient of this supposed letter, John Hill, had never actually existed, throwing doubt on the entire Rillbank Collection. MacKenzie later published two ‘Burns’ poems in the same paper, only to discover that one of them had been written when Burns was only 7 by an entirely different poet! Other forgeries were discovered in the collection of an American, who had purchased letters from Edinburgh manuscript collector James Stillie.

By now, word was spreading about the forgeries. In 1892, The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch published an article on the issue, and a reader recognised the handwriting on the facsimiles included as that of Smith, at that time working as chief clerk for a lawyer, Thomas Henry Ferrie. Smith was duly arrested and his trial began on June 26th 1893.

Smith was charged with selling forgeries under false pretences. He was found guilty, but the jury recommended leniency and he was sentenced to 12 months. Experts later said that some of his forgeries were not of particularly high quality – often they were dated after the death of their supposed writer, or created using modern paper or writing tools. It is more than possible that many of those who sold his forgeries on would have been fully aware that they were not genuine. It is unknown exactly how many of ‘Antique’ Smith’s forgeries are still around, but we do know that we have some of them in our collection!

Burns’s Commonplace Books

Commonplace Books first became significant in early modern Europe as a way of compiling knowledge. ‘Commonplace’ is a translation of the Latin phrase locus communis which means ‘a theme or argument of general application’. This original definition has been expanded to now mean a collection of materials on a certain theme by an individual. Importantly, commonplace books are not diaries or journals, as they are structured thematically rather than chronologically, and do not necessarily relate to the personal lives of their compilers. By the 17th Century, commonplacing was prevalent enough to be formally taught at places such as Oxford University, and there is a strong tradition of literary figures such as John Milton, Mark Twain and Thomas Hardy compiling them.

There are two commonplace books belonging to Robert Burns in existence. The first, begun in 1783, was almost certainly not intended for publication, and entries cease in October 1785. The second, begun in Edinburgh in 1787 and sometimes referred to as the Edinburgh Journal, has many interesting entries including early versions of the Bard’s poems and musings on people he knew. On its first page, Burns explains his desire to record his experiences in Edinburgh (where he had just moved), and his observations on the people he has met, while they are still fresh in his mind. He quotes Gray, saying ‘half a word fixed upon… is worth a cart load of recollection’ showing his preference for the written word over memory.

Near the beginning of the Book, Burns starts a discussion relating to his patron, the Earl of Glencairn, and laments the fact that a man with little talent and high social status (the Earl) would naturally be treated with more respect than a man of genius but low social status due to an accident of birth. He says, with similar sentiment to his work ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ That’:

Imagine a man of abilities, his breast glowing with honest pride, conscious that men are born equal, still giving that “honor to whom honor is due”; he meets as a Great man’s table a Squire Something, or a Sir Somebody; he knows the noble landlord at heart pays gives the Bard or what- ever he is, a degree o share of his good wishes beyond any at table perhaps, yet how will it mortify him to see a fellow whose abilities would scarcely have made an eight penny Taylor and whose heart is not worth three farthings meet with attention and notice that are forgot to the Son of Genius and Poverty?

Burns does confess to being torn, however, because Glencairn was so pleasant to him when they met.

Also near the start of the book is a first draft of the song ‘Rantin’ Rovin’ Robin’ referring to the incident in which the gable end of Burns Cottage blew down during a storm in the first few weeks of Robert’s life. Interestingly, in this version, the opening line is ‘There was a birkie born in Kyle,’ as opposed to ‘there was a lad was born in Kyle’. There are then two versions of a poem written in Carse Hermitage on June 1st 1788, with a note beside the first draft instructing the reader to instead read the second draft further into the book. There is also a draft of his more famous poem, On seeing a wounded hare, along with other notes on his works.

Burns’s second commonplace book is on display in our museum collection and is a fascinating insight into some of the Bard’s personal thoughts, and also on how he drafted his poems. We wonder how many of our readers keep scrapbooks of this kind?

Robert Burns’s Seal

The creative talents of Robert Burns extended beyond his poetry and songs when he decided to design his own seal in 1794. In the medieval era a badge like this would have had aristocratic or militaristic origins. So why did a humble farmer poet, who was a believer in love rather than war, want a coat of arms? Burns’s creation can be seen imprinted in crimson wax and on his seal matrix within the exhibition collection at Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. This seal was a public declaration that Burns considered himself equal to any nobleman, and this would have given a clear signal to any that would have seen it. This was an important token of personal and familial identity for Burns, which he would have imprinted onto his letters.

Burns decided to incorporate two mottoes within his seal. ‘Wood-notes wild’ is inscribed across the top of the seal, whilst along the bottom there is the phrase ‘Better a wee bush than nae bield’ (shelter). The first inscription could be signalling how nature has often been an important inspiration in his life, both visually and musically. He often said his wife Jean had the sweetest wood-notes wild singing voice. In the second motto Burns could be highlighting his fears of homelessness that frequently haunted him towards the end of his life. This reminds us to respect Mother Nature, as she can be a refuge for a wee mousie to all mankind as well. In the centre of these two mottoes Burns has placed a shepherd’s crook and pipe, signalling his lifelong connection to nature through his agricultural background.

One of the main elements in his design is a Holly Tree at the bottom. Perhaps Robert Burns wanted to display his love of nature prominently, or perhaps there is another layer of meaning to consider. In Celtic mythology a Holly Tree was a guardian in the dark, winter months. It was seen by the people as a symbol of peace and goodwill. Furthermore, the Druids believed that Holly possessed protective qualities and that it could guard against bad luck and evil spirits. Therefore, this could be Burns recalling his time as a child when he heard stories of folklore and superstition from his mother and Betty Davidson.

A woodlark is a symbol of cheerfulness and joy even in the worst of times, something that Burns would have related to as his own spirits rose and fell throughout his life. But the similarity between Burns and the woodlark does not end there, since this particular song bird can mimic and remember other birds’ songs. Burns was a great lover of songs and music since boyhood, so in order to preserve the traditional songs of his beloved Scotland; Burns dedicated himself to collecting them. These were gathered together and published in an anthology called Scots Musical Museum by James Johnson over several years.

In the closing decade of the eighteenth century, discussion on republicanism and equality were politically rife questions. Robert Burns did not meet the requirements to vote; as such he used his pen and voice to challenge the political authority of the time. In his seal matrix Burns has placed a woodlark upon a branch of bay leaves. In Roman mythology bay leaves were treasured by the Gods, as their crowns of bay leaves connoted their high status and glory. By placing a woodlark, a song bird like himself on top of the branch, Burns could be trying to say his voice has greater potency then the established authority. In addition to this, it could also be interpreted as a form of mockery, as a single songbird could undermine the glory of those in power with his voice alone.

Burns deliberately incorporated multiple layers of meaning within several of his poetical works, and this mastery of disguising his true intention could also be said for his seal. Did he choose these symbols as a way of showing the world how he saw himself or how others saw him? Whether you believe these symbols have multiple meanings or not, it still provides an insight into how Burns wanted to be portrayed and remembered. He was a lover of nature and song, and even in his height of popularity amongst the literati of Edinburgh he never forgot his farming roots, which is evident in the shepherd’s pipe and crook in the centre. Nevertheless Robert Burns was a man not afraid to aspire beyond his supposed class, and this small seal and wax impression is evidence of this.

By Kirstie Bingham

The book that went to space…

In November 2009, a small book containing 14 Burns poems and songs was presented to astronaut Nick Patrick by ten young Scots taking part in the Scottish Space School. This book was to make a 5.7 million mile journey the following February, completing 217 orbits of the Earth on a two week long mission to the International Space Station.

The Scottish Space School is an initiative delivered by the University of Strathclyde, designed to encourage young people to consider careers in science and engineering. These particular students were taking part in a trip to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Texas, where they were able to hand the book over to Nick Patrick. Originally, the book was given to the Space School by Alan Archibald, a distant relative of Jean Armour, Burns’s wife. It made its out of this world trip to celebrate the Year of Homecoming in 2010 aboard NASA’s STS 130 Endeavour spacecraft.

The book is now part of our museum collection, alongside a photograph of Nick who said:

‘It was a real honour to have met such an enthusiastic group of young people, not only to continue the inspirational work undertaken by the Scottish Space School, but to also help spread the timeless poetry of Robert Burns.’

Excise Pistols

This blog was written by Iona Fisher, a work experience student from Carrick Academy.

In 1788 Burns trained to be an excise officer and was an excise man until he died in 1796, as well as farming in Ellisland. Excise men (also known as gaugers) covered large areas of Scotland’s countryside and their job was to inspect and record taxable materials, such as malted grain, soap, candles and paper, before and after they were manufactured. To do this Burns would use dipping rods to measure liquids and scales to weigh dried materials. Burns was aware that people did not necessarily like excise men, so he carried a pistol around with him to protect himself.

Also in RBBM’s collection are Robert Burns’s duelling pistols: http://www.burnsmuseum.org.uk/collections/object_detail/3.8557.a-c

With Robert Burns’ health condition getting worse, he moved back to Dumfries to live his last few days. On his deathbed he gave his physician – Dr William Maxwell, his pair of duelling pistols. He died in Dumfries on the 21st of July 1796 from a heart disease. Roberts’s wife, Jean, gave birth to her last child the day of Burns’s funeral and she named him Maxwell after Robert’s physician. The pistols were donated to the Burns Monument Trust by William Hugh Fleming in 1987 and they are now in the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum.

The Beggar’s Badge – any spare change?

The final blog post in our series written by two placement students from Glasgow University is on the Beggar’s Badge in the museum.

It doesn’t matter who you are, where you live or what you do for a living: you will have come across beggars in some context. Whether that experience is witnessing people begging on the streets of a busy city, or being approached by someone asking for money on public transport, begging is one of the few features which appears to be current in most cultures. Tolerated in some countries, looked down on in others; the presence of begging appears to be both a problem for society and a means of survival for individuals. With the high population of beggars seen today in streets all over the world, it is easy to justify not financially helping individuals due to the overwhelming size of the community. However, perhaps it is time we stopped looking for change in our wallets and purses and instead look at the change we can spare from ourselves.

The beggar’s badge on display in the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum only emphasizes how constant this problem is in society, and the different attempts that have been made to ‘fix’, or at least control, it. It seems quite bewildering that we have managed to go for so many centuries, with no success of fixing this issue. But how can it be fixed?! Alongside the badge in the museum is an edition of The Big Issue, a modern-day scheme which provides a ‘hands-up’ approach to aid solving the problem, giving people in hopeless positions an opportunity to find hope through their own actions. With these items paired together in the museum, the timelessness of the problem of urban poverty and homelessness becomes even more prominent. Though the modern-day scheme of The Big Issue magazine, the people in these vulnerable life-states are empowered, there is still a separation in the wider community today. In all these attempts to tackle the ‘big issue’ are we really just avoiding the issue at the core of the problem? Perhaps the issue is not the presence of beggars on the street, but instead our attitudes towards them?

Today, attitudes toward beggars are not what most people would describe as positive. Often avoided and ignored, those sitting on the street asking for help are subject to both financial and social poverty, in the lack of acknowledgement they are given. Here in the UK street begging is illegal, making it not only socially frowned upon but lawfully as well.

With this in mind, it seems that Burns’s poem ‘The Jolly Beggars’ challenges this view today. It not only goes so far as to acknowledge this community of people, but also to romanticize their situation and their ‘freedom’ from responsibility. How different this view of the homeless is from the one displayed today. Though Burns is obviously not representing the views of his community through this poem, he is providing a new take on the begging community that has for so long been looked down on in so many different cultures. In a documentary by Power and People, Barnaby Phillips investigates the differences that begging has on the culture in Sweden and in the Philippines. At the end of this 30 minute film, Phillips states that despite the differences in how the issue is handled in both countries, the common denominator of both cultures is the ‘growing gap between the rich and poor’ in society. So, if the real issue is the class divide in our society, is this not something that we have the power to improve? Or are we all out of spare change?

By Kathryn Thompson

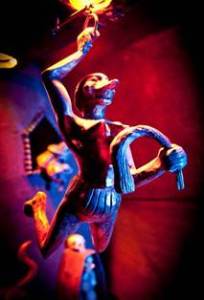

Professor Sharmanka’s Magick Sheddae Schaw

Visitors to the museum lately can hardly help but have noticed our latest temporary exhibition – ‘Witches’ Brouhaha Spooks and Spells’ by Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre. Sharmanka, which is the Russian word for ‘Barrel-Organ’, is a collaboration between sculptor-mechanic Eduard Bersudsky, theatre director Tatyana Jakovskaya, and light and sound designer Sergey Jakovsky. You can see more of their work at Trongate 103 in the centre of Glasgow.

The exhibition consists of five ‘Kinemats’, or motorised machine sculptures – carved figures and pieces of old scrap which perform an incredible choreography to haunting music and synchronized light. One is themed on Burns’s famous poem ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ and the other four are all themed on witches, giving the whole exhibition a Burnsian feel. Due to the nature of the exhibition, shows are timed throughout the day and are introduced by our hard-working volunteers, but the exhibition is open for viewing the sculptures between shows as well. It runs until February 28th and is free! Why not pop down and see it one day and bring the family? Shows last approximately ten minutes.

Alongside the exhibition itself, our new Scots Scriever (poet in residence) Rab Wilson has written a fantastic poem in Scots to compliment the show:

Professor Sharmanka’s Magick Sheddae Schaw

Wheesht! Whit’s gaun oan in the Burns Museum,

In the howe-dumb-deid o the wee sma hours,

Thair’s eldritch whigmaleeries cam alive,

Tae fleg the weans oan this All-Hallow’s Eve!

Professor Sharmanka’s traivellin schaw,

Trundles ower the Brig O’Doon’s auld keystane,

An frae his cairpet-bag cam’s crawlin oot,

A damned menagerie o infernal craiturs!

Whan nae-yin is abraid they tak their post,

Heizin scrap-yaird treasuirs intil place,

Bits o cast-iron Singer shewin machines,

A pair o auld pram wheels, a lavvie cistern.

The doors frae a bracken doll’s hoose kythe,

Blinkin de’ils Hieronymous Bosch wid ken,

Biggin their Heath Robinson contraptions,

Ilk beam an ratchet fixed, when naethin steers.

Uncanny bears an wolves an burly bulls,

Rax an jundy, streetch an rax an puhl,

Wi aa their micht an main, wi sweit an thew,

Til evri gear an wheel an pinion’s fixt.

Sharmanka taks his concert-maister’s place,

Syne shoogles his sauch wan an gies a tap,

Ilk craitur in their place taks tentie care,

An then a kist o whustles girns tae life!

Rid lichts lowe oot, glentin lik damnation,

The eerie music rises tae its pitch,

The strainin chains growe taut, the gear-wheels catch,

An syne the hale clanjamfrie jyne the dance!

Sharmanka’s airm flails lik a Tattie-Bogle,

Claucht in some back-end November storm,

Whiles oan their heich trapeze the ferlies birl,

The Tod an Yowe, a Bear wi bairn in airms,

Lood an looder screichs the Deevils score,

The hale queer unco’s gaun lik a fair!

The ragged Gaberlunzie’s Hurdy-gurdy,

Adds its timmer-tuned vyce tae the choir.

Chained in their wee bit hoosie, backs tae the licht,

The ‘Children o the Daurk’ jalouse frae sheddaes,

The warld they ken frae saicent-haund daylicht;

Cantrips dancin oan the wa afore thaim.

An aa the hoose around is sleepin soundly,

Anely a doverin Houlet blinks an ee,

Douce fowk o Ayr! Gin anely ye cuid see!

Sharmanka’s diabolical Kinetics!

When aa a suddent, chanticleer dis craw,

The dancin stoaps an lichts aa fade awa,

Sharmanka pynts his wan i the risin sun,

The Houlet shaks his feathers, aa’s gaen lown.

The Gallery door’s flang apen tae the public,

A mither wi her twa bit bairns gangs furth,

The auldest lassie rugs her mither’s sleevie,

‘Mammy, mammy! Thon bear winkt its ee!’