Month: July 2015

#ilovemuseums because of the unique collections!

A previous blog post looked at the ‘up-cycling’ of the press that printed Burns’s first collection of Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect also known as the Kilmarnock Edition. The repurposing of the press happened in 1858 and it was turned into an arm chair. The chair became an ornamental and useful piece of fine oak furnature, that was a souvenir or relic of Burns’s inaugural work.

This is not only one example of creating souvenirs or relics relating to Burns’s work and life from materials which are linked to aspects of his fame and life. At the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum and Bachelors Club, Tarbolton there is an amazing array of material! This blog post will look at a few highlights in the collection.

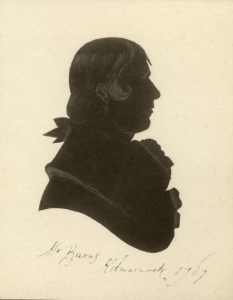

From the passing of Robert Burns on the 21st of July 1796 at the age of 37 people wanted to own a piece of the man! Over the years after his death the “Burnsiana”[1] grew and developed, the collection of Burns souvenirs is broad and includes material that has been up-cycled from other objects or materials include pieces of Burns Trysting tree made into collectables, hair jewellery made with pieces of Jean Armour’s hair and pieces of Burns’s kist/coffin.

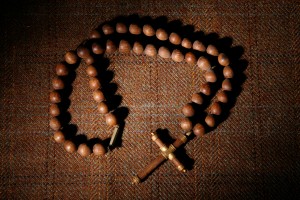

An interesting item in the museum collection is a necklace that is in the Fame section of the museum display. The necklace has 40 wooden beads and a wooden cross at the front with metal embellishments. It is 54cm long and the wood used in the necklace was taken from the Auld Alloway Kirk, just a short walk from Burns Cottage and next to the Burns Monument.

Alloway Kirk is a ruined church, which was built about 1516. By the time Burns wrote Tam O’Shanter the Kirk was in ruins. It had not been used for several decades and was in a ruinous state.

There is little information within the object record other than that the necklace is dated to 1822 – which dates to when Burns Cottage was under the tenancy of John Gaudie, and when the Burns Monument was under construction.

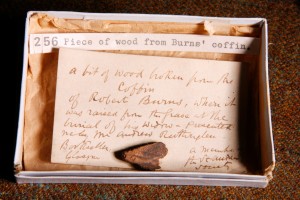

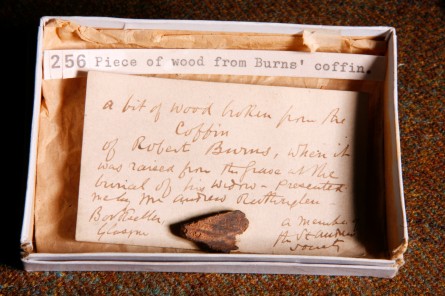

Other unique wooden souvenirs in the collection include a Pipe Case reportedly made from part of Burns’s Kist (3.4572), this is not unusual in the sense that it is connected with Burns’s burial – with the acquisition dated to 1834, below is an image of a piece of wood taken from Burns’s coffin when his tomb was opened so that Jean could be buried alongside him.

As with many souvenirs or relics the authenticity of the object is unclear – in this case eyewitness accounts state that the coffin was intact.

Wooden souvenirs with a direct connection to Burns’s life, made from the wood of trees grown on the banks of the Doon or, in this case, from the rafters of Alloway Auld Kirk, were highly sought after by Burns enthusiasts and general Victorian collectors.

In the 19th century there was a real interest in relic collecting relating to contemporary Poets – for instance at Keats House, Hampstead has in the collection a Gold Broach with some of Keats’s hair displayed in it, c.1822 (K/AR/01/002); another relic kept by the British Library is Percy Shelley’s ashes set inside the back cover of the book Percy Bysshe Shelley, His Last Days Told by His wife, with Locks of Hair and Some of the Poets Ashes (MS 5022).[2]

At RBBM we have a lock of our Poet’s hair which is said to have been snipped from Robert’s head shortly after his death by his wife, Jean Armour, and given to her friend Jean Wilson in Mauchline as a macabre souvenir.

The world of Burns souvenirs and relics is vast and this only highlights some of the more unique… and interesting aspects of Burnsiana!

[1] Mackay,.J.A Burnsiana (1988)

[2] Lutz,.D Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (2015).

by Catriona, Learning Intern

The Mysterious Illness of Robert Burns

On the 21st of July Robert Burns, the national bard of Scotland, died at the young age of 37. In a world where famine and disease frequently wreaked its havoc, early death was often common. However, for those who lived past the diseases of childhood, long life was a definite possibility. So, even in the eighteenth century, Burns’s death seemed premature and tragic. But what did Robert Burns die of? This is a question that has puzzled Burns scholars for many years and is often asked by our visitors. Yet, upon looking at the history, Robert Burns’s medical problems seem to be complex, with a range of symptoms and complaints.

One major influence on his health throughout his life was his struggle with mental health.

For example, as a young man living in Irvine, Burns suffered a terrible breakdown. Described as hypochondria at the time, he suffered from what we would now describe as a serious case of depression and anxiety. This depression would return to him periodically when he had financial struggles, problems with his love life, or when he found himself in difficulties due to his politics. At these times, he was often incapacitated by his depression. For example, in December 1789 he wrote to his friend, Mrs Dunlop, saying that ‘For now near three weeks, I have been so ill with a nervous headache, that I have been obliged for a time to give up my exercise books, being scare able to lift my head.’ Certainly, his tendency to succumb to depression didn’t help him as physical symptoms appeared in his 30s as he stated that, ‘‘My Physician assures me that melancholy and low spirits are half my disease.’

It therefore seems that depression was a contributor to his death, but as we get into the mid 1790s, it is quite clear that Burns is suffering from serious physical complaints. In 1795 he complained of ‘the rigid fibre and stiffening joints of old age coming fast o’er my frame’ and although he was only 35, he seemed to have begun to feel like an old man. This progressed into the year with him complaining about toothache and weakness, saying at one point that he felt barely able to lift his pen. On some days it appears he struggled to get out of bed, while between December 1795 and 1796, the death of his 4 year old daughter gave him rheumatic fever. He seemed to recover in the spring of 96, but a remark in his letter to his friend Thomson perhaps shows that the end was near: ‘Rheumatism, Cold and Fever, have formed, to me, a terrible Trinity in Unity, which makes me close my eyes in misery and open them without hope.’ Certainly, as spring turned to summer, those who saw him said he looked ‘consumptive’ and like he was ‘already touching the brink of eternity.’

In July, a last ditch attempt of a cure was sought and Burns was advised to travel out to the Solway Firth and immerse himself in the water. However this did not seem to work as he wrote letters saying that he was incredibly weak, with no appetite, and barely able to stand. On returning to Dumfries, his friend John Syme recorded him as being emaciated and shaken and that death seemed certain. And only a few days later it was over – Robert Burns was dead.

So what was this mysterious illness? Modern doctors looking at these accounts seem to think that Robert Burns died of a heart condition Endocaritis and believe that the sea-bathing ‘cure’ recommended to him probably hastened his death.

How did you become…a museum director?

My first memory of being in a museum was visiting Dick Institute in my home town of Kilmarnock. The look and smell of the place made a strong impression: classical architecture, mosaic floors and a bronze statue in the entrance, the smell of dark wood and polish, and the natural history specimens on display upstairs. With its imposing classical facade and Romanesque decoration, I’m sure I thought at the time that it actually was Roman (in fact the building dates from 1901). My next memory of heritage of any kind was on a school visit to Dean Castle . We were shown around the stone keep and taken to see some cannon on the lawn outside. I was struck that heavy duty history could live so close to me and I can still remember the metallic smell of damp gunpowder on the winter air.

I was an average school pupil who worked hard in upper secondary and got good grades. I had only studied one science at ordinary grade – biology – so played catch-up in 5th year to take a second science subject, Chemistry. I was still sufficiently interested in both subjects to put Biochemistry on my UCAS form. To be honest, as the first person even in my wider family to consider university, it all seemed very unreal, very unlikely. Biochemistry became Chemistry at University of Glasgow and I left with a degree three years later but with little inclination to use it. Towards the end of my degree I’d began to read some classic fiction – Dickens, Balzac, Turgenev, and others. I’d also started to travel more and more. Eventually, I moved to different parts of England, Wales, and Ireland, working in youth hostels, travelling, reading, and, eventually, turning my attentions to an arts degree with the Open University.

Towards the end of this degree (English Literature and History) I began to wonder what I should do next. At that time I was living in Pembrokeshire, in South West Wales, working in a field study centre. I wrote to Pembroke Castle and to Tenby Museum and Art Gallery, two of the biggest attractions in the area, to volunteer my services. Pembroke Castle wrote back asking me to rewrite some interpretive panels (for which I was paid) and Tenby invited me to volunteer with them one day per week.

Perched on a cliff overlooking St Catherine’s Island, Tenby Museum and Art Gallery is a small, independent museum supported by a few paid staff a large and lively volunteer workforce. It has an extraordinary collection of modern art, reflecting the importance of Tenby and Pembrokeshire to artists such as Gwen and Augustus John, Graham Sutherland, and Philip Sutton. Over the winter of 1996, I was asked to catalogue some of their archive. I was given pretty much free reign to sort and research a backlog of papers. To my great surprise, among some unexceptional bits and pieces I discovered a manuscript of an unpublished poem in the hand of Laurie Lee, who used to summer in Tenby. The spirit of the volunteers, and the flamboyance of the then Director, John Beynon, made a deep impression. I decided I’d become a curator and proceeded to take a master’s degree with the University of Leicester. This was by distance learning which allowed me to work to pay for the degree and, eventually gain some first hand experience in museums. My first post was as curator of Burns House Museum in Mauchline. The museum and its fine collection of Burnsiana was in a period of transition, passing from ownership by Glasgow and District Burns Association to East Ayrshire Museums. Working with the local community, I reorganised the collection and experimented with different ways of making the exhibitions more interesting. It was the perfect way of cutting my teeth and building my confidence.

Because I’d worked closely with the community, at the end of the season I got a job with the Open Museum, the outreach wing of Glasgow Museums. My role was to work with a team of volunteers to put together exhibitions in a leisure centre in Pollok. The project, called the Greater Pollock Kist, aimed to stimulate greater community use of the City’s collections and encourage people from G53 to visit their ‘local’ museum, the Burrell Collection. Working with such a diverse group of people was good preparation for my next position; project officer on an initiative called the Distributed National Burns Collections Project. Over 15 months I worked with 25 different institutions finding out more about their Burns collections and using this information to form a scoping study report, website, joint database, educational resources, and strategic road map. The project was based at Burns National Heritage Park and did much to make the case for greater awareness of the size and significance of Scotland’s distributed literary collections leading, arguably, to the transformation of the birthplace and to Recognition of the National Burns Collection in 2009.

On completion of the project, I moved to the University of St Andrews, setting up the Gateway Galleries and developing plans for a new university museum, MUSA. By 2006, the National Trust for Scotland were leading the redevelopment of Burns National Heritage Park, becoming owners of the site and the collection in 2008. The Trust needed a curator and someone who knew something about Burns and they imagined that I fitted the bill. In many ways, I was a harbinger for NTS in Alloway; I was the first member of Trust staff and worked closely with Burns Monument Trust and South Ayrshire Council to prepare for the handover of the collection and its decant from the old museum building beside Burns Cottage. The four year project to design and build the new museum was hard work but it was, for me, the opportunity of a lifetime to do Burns and the collections justice. In the process of working on the new exhibitions, I really enjoyed the research element but because of the pace of the project, one could never spend nearly enough time on one particular area. After the speeches on the day the museum officially opened on 21 January 2011, I left for a research fellowship with the Shakespeare Institute and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. The fellowship combined practical projects, such as the development of an app called Eye Shakespeare and the writing of digital strategies, to a doctorate focusing on how digital technologies and environments affect how we interact with artefacts. On its completion I joined the School of Museum Studies at the University of Leicester for a short time covering for a research associate on maternity leave. During this time, I applied for a curator position at a literary museum in London. The director who interviewed me informed me afterwards that I wouldn’t be offered the position but that I should consider applying for his job coming up in a few weeks. Having spent 10 years as a curator, and then 3 as an academic, I was ready for a challenge and this seemed like the right time for me to try a management role. Coincidentally, the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum was also looking for a director at that time which I applied for and got. I now have the privilege of leading the museum I helped to create and which, in its own way, helped make me.

Returning to Dick Institute today, mainly on work business, I am still humbled on entering the building and still struck by a childlike awe which I hope never leaves me.

The Voice of Nature

Nature is one of Robert Burns’s favourite themes for his poetry, from his early years at Burns Cottage, to his days farming by the River Nith, living and working in rural Scotland provided him with great inspiration. For example, from his time living near Mauchline, he wrote the poem Sweet Afton, which describes the beauty of the countryside in which he and Highland Mary courted:

How pleasant thy banks and green vallies below,

Where wild in the woodlands the primroses blow;

There oft, as mild ev’ning leaps over the lea,

The sweet-scented birk shades my Mary and me.

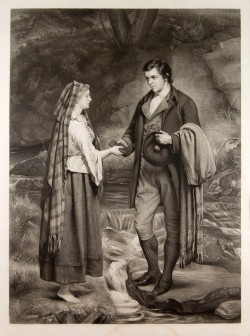

R. Josey and James Archer.

1882, permanent collection

Burns also saw greater themes of life emerge from watching the process of nature. In To a Mouse and To a Mountain Daisy he reflects on the uncertainty of the future, the fragility of life, and his own struggles with depression and the future:

Ev’n thou who mourn’st the Daisy’s fate,

That fate is thine – no distant date;

Stern Ruin’s plough-share drives elate,

Full on thy bloom,

Till crush’d beneath the furrow’s weight

Shall be thy doom!

In addition to this, a sense of place was very important to Burns as he used local places in poems like The Twa Brigs of Ayr, and Tam O’ Shanter. In the latter poem, the connection between people and place results in many powerful and evocative descriptions:

In addition to this, a sense of place was very important to Burns as he used local places in poems like The Twa Brigs of Ayr, and Tam O’ Shanter. In the latter poem, the connection between people and place results in many powerful and evocative descriptions:

And thro’ the whins, and by the cairn,

Whare hunters fand the murder’d bairn;

And near the thorn, aboon the well,

Whare Mungo’s mither hang’d hersel’

Thus, this summer, we are celebrating these inspirations with an exhibition called The Voice of Nature, which features three unique artworks.

The first of these artworks is by Mathew Dalziel and Louise Scullion, who have created two video pieces which combine visuals and spoken word to recreate our oral culture and relationship with nature. Our curator Sean McGlashan states that these works are, “comparable to the best films of nature but are also works of art with original words and music. I think Robert Burns would love them.”

In addition to this we also have a ‘sound sculpture’ by Laura Graham at Auld Kirk Alloway, the site of Tam O’ Shanter’s drunken encounter with the local witches. Every 20 minutes visitors at the Auld Kirk will experience the sounds of the witch’s dance as heard by two Kirkyard ravens, bringing the story of Tam O’ Shanter to life.

The last artwork in this exhibition is Chieftain by sculptor Jake Harvey, whose work is about attaining simplicity and clear form. This sculpture, which is a permanent piece on our Poets Path, celebrates the haggis, or ‘chieftain of the pudding race,’ that Burns so enjoyed consuming. Made of granite, this sculpture will glisten in the rain and sparkle in the sunshine.

As you explore our site we hope that you happen upon these artworks and are inspired to think to about our relationship with nature and the places we live!

The Voice of Nature is free and runs until Sunday the 25th of October.