Month: February 2018

Burns’s Commonplace Books

Commonplace Books first became significant in early modern Europe as a way of compiling knowledge. ‘Commonplace’ is a translation of the Latin phrase locus communis which means ‘a theme or argument of general application’. This original definition has been expanded to now mean a collection of materials on a certain theme by an individual. Importantly, commonplace books are not diaries or journals, as they are structured thematically rather than chronologically, and do not necessarily relate to the personal lives of their compilers. By the 17th Century, commonplacing was prevalent enough to be formally taught at places such as Oxford University, and there is a strong tradition of literary figures such as John Milton, Mark Twain and Thomas Hardy compiling them.

There are two commonplace books belonging to Robert Burns in existence. The first, begun in 1783, was almost certainly not intended for publication, and entries cease in October 1785. The second, begun in Edinburgh in 1787 and sometimes referred to as the Edinburgh Journal, has many interesting entries including early versions of the Bard’s poems and musings on people he knew. On its first page, Burns explains his desire to record his experiences in Edinburgh (where he had just moved), and his observations on the people he has met, while they are still fresh in his mind. He quotes Gray, saying ‘half a word fixed upon… is worth a cart load of recollection’ showing his preference for the written word over memory.

Near the beginning of the Book, Burns starts a discussion relating to his patron, the Earl of Glencairn, and laments the fact that a man with little talent and high social status (the Earl) would naturally be treated with more respect than a man of genius but low social status due to an accident of birth. He says, with similar sentiment to his work ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ That’:

Imagine a man of abilities, his breast glowing with honest pride, conscious that men are born equal, still giving that “honor to whom honor is due”; he meets as a Great man’s table a Squire Something, or a Sir Somebody; he knows the noble landlord at heart pays gives the Bard or what- ever he is, a degree o share of his good wishes beyond any at table perhaps, yet how will it mortify him to see a fellow whose abilities would scarcely have made an eight penny Taylor and whose heart is not worth three farthings meet with attention and notice that are forgot to the Son of Genius and Poverty?

Burns does confess to being torn, however, because Glencairn was so pleasant to him when they met.

Also near the start of the book is a first draft of the song ‘Rantin’ Rovin’ Robin’ referring to the incident in which the gable end of Burns Cottage blew down during a storm in the first few weeks of Robert’s life. Interestingly, in this version, the opening line is ‘There was a birkie born in Kyle,’ as opposed to ‘there was a lad was born in Kyle’. There are then two versions of a poem written in Carse Hermitage on June 1st 1788, with a note beside the first draft instructing the reader to instead read the second draft further into the book. There is also a draft of his more famous poem, On seeing a wounded hare, along with other notes on his works.

Burns’s second commonplace book is on display in our museum collection and is a fascinating insight into some of the Bard’s personal thoughts, and also on how he drafted his poems. We wonder how many of our readers keep scrapbooks of this kind?

A Love of Dancing

Poetry, songs and women are widely known to have been Robert Burns’s great passions, but he also loved to step onto the dancefloor as well. In 1779, Burns as a young man decided to attend dancing lessons in Tarbolton. This decision allowed him to temporarily escape the financial difficulties that the family were enduring at Lochlea. Therefore Burns used to regularly walk to a humble thatched house after the farming work was done to enjoy some time with his friends. In the museum collection you will see a beautifully restored fiddle with a red, green and black floral design work. This fiddle was played by Burns’s dance teacher, William Gregg, while Robert learned and practiced his steps. According to Burns he took up dancing to ‘give my manners a brush.’ But improving his manners and exercise were not the only benefits that dancing would give, as it granted Burns an opportunity to get acquainted with the local girls as well. This early time of social and sexual exploration played an important part in shaping Burns into the man he would famously become. To our twenty-first century minds dancing seems like a harmless pastime; but to his father William Burnes, this was an act of rebellion. According to Gilbert their father was often irritated by Robert’s dancing, as it was a clear sign that Robert was no longer listening to William’s advice and counsel. As a consequence of this, Burns himself acknowledged that his decision to continue with his dancing lessons compromised his relationship with his father.

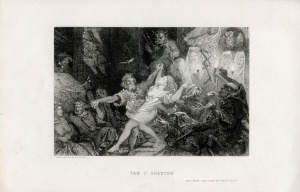

In Burns’s narrative poem Tam O’Shanter you can feel the excitement of the dance unfolding, yet all the while there is a dark truth to this particular social gathering:

Warlocks and witches in a dance:

Nae cotillion, brent new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.’

This scene of enjoyment is not only watched by the protagonist Tam, but also by Auld Nick who played the music to make them dance. This negative perception of dance being sinful is more in keeping with William’s opinion rather than his son. Nevertheless this moral outlook is undermined by the poem’s greater sense of adventure and humour. These two opposing viewpoints mirror the different standpoints of William and Robert in 1779, one saw dance as wicked and the other saw only pleasure. Despite all of William’s disapproval Robert Burns continued to love music, dance and social gatherings throughout his life. Tam O’Shanter was published in Grose’s Antiquities of Scotland in 1791, which reveals that Burns never forgot his father’s outlook on dance.

If you are a lover of dance yourself, you can follow in the Bard’s footsteps and take part in Scottish country dances set to his songs. For instance Ae fond Kiss is a reel, or perhaps you would prefer a livelier jig to the poem Halloween. One of the most popular times to toast Burns and celebrate his life is at a Burns Supper, so perhaps in the future you will follow his example and take to the dancefloor.

‘The dancers quick and quicker flew,

They reel’d, they set, they cross’d, they cleekit.’

Tam O’Shanter

By Kirstie Bingham